HILLMAN WWII SCRAPBOOK

HMCS PRINCE ROBERT

Presents

7. HONG KONG 1945

COMMISSION #4 CAPT. W. B. CREERY RCN 04.06.45

After a strenuous month of working up, the ROBERT sailed on July 4th for Sydney via San Francisco. At this point she became a unit of the British fleet and sailed through the Coral Sea to Manila where the task force was mustered for an attack on Hong Kong. The problem of re-occupation was not helped by the American reluctance for the recovery of British colonial territory. With this delicate point unresolved, the formidable task force of two fleet carriers, INDOMITABLE and VENERABLE, two cruisers, SWIFTSURE and EURYALUS, 14 destroyers, minesweepers, the eighth submarine flotilla and a hospital ship was assembled by the British admiral.

The force was mustered in Subic Bay, but by this time, the atomic bombs had been dropped and the Japanese had capitulated. Their empire was on its knees with all lines of communication cut. Hong Kong was isolated with a garrison of only about 15,000. Plans were changed and the ROBERT was given the option of going to Tokyo for the surrender, going to Formosa where trouble was brewing, or carrying on to Hong Kong. The choice was obvious.

Positions were taken up some twelve miles outside the harbour near the island of Kam Tan. Japanese representatives were brought off for conferences on the flagship and an agreement was made for the conduct of both sides upon our entry to Hong Kong. Rumours of an attack by Kamikaze torpedo boats were causing concern. None developed and, in fact, the ROBERT secured one and brought it back to Canada as a museum piece.

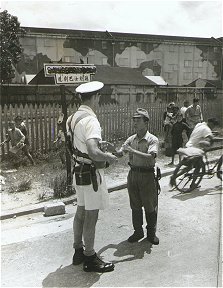

The ROBERT was the fifth ship to enter and after a very cautious examination of the Kowloon dockside, tied up on this mainland shore, the sole vessel to do so. Landing parties, which had been given such intensive training both in Comox and in passage were formed. When the ROBERT made fast to Holt’s wharf on the 30th August, there were shrieks of joy from the Chinese onlookers. This was mainly due to the powerful armament of the flagship which was in full view in the harbor.

Excerpt from Captain Creery’s report:

“The wharf was occupied by armed Japanese soldiers, who, contrary to the terms made a Kam Tan, were removing goods from the godowns and loading them into a small freighter alongside the wharf just ahead of the PRINCE ROBERT. We put our landing party onto the wharf and ordered the Japanese to lay down their arms, desist from loading the freighter and to leave the wharf. Trouble was obviously brewing; taking with me a very large AB armed with a Tommy gun, I landed to see what it was all about. The Japanese CO politely informed me that it was contrary to the Kam Tan agreement for his soldiers to be disarmed. I made some polite remarks about the freighter and for a few moments we looked at one another contemplatively. It was tense but finally his eye wavered and he gave the order for his troops to march off unarmed and proceeded toward a waiting car. We didn’t think much of that idea and told him that all cars on the wharf were commandeered. Again there was a pause for thought and an eyeball to eyeball confrontation but finally with a shrug, he departed.”The Chinese started looting, thinking they could take advantage of the loss of Japanese authority. The landing party consisted of about 140, and of course, in any show of force against the current garrison was completely inadequate. However, an arrangement was made with the Japanese commander where his forces remained to police the town until relieved by more adequate authority. With due respect to the Japanese, they kept their side of the bargain in good faith and there was actually less trouble than when the regular British forces arrived.

Naturally the first thoughts of all were to release the Canadian prisoners who had been held in Sham Shui Po prison for 45 months. The landing party from the ROBERT were there first, and were met with scenes of wild enthusiasm from everyone. The prisoners were emaciated and had suffered severe deprivation during their incarceration. However, thanks to the high standards of morale and discipline they had maintained while in captivity, they appeared to be in much better condition than anyone had reason to expect. However, it was a rough time for most of them when they attempted to re-enter the life style of Canadian eating and drinking. The crew of the ROBERT emptied their larders, their stores and their luxuries for these unfortunate men. On the whole, the matter of maintaining law and order in a city of 1,500,000 went rather smoothly, which was no small credit to the ROBERT’s crew.

The final surrender of Hong Kong took place on September 16th with Captain Creery as one of the signatories for Canada. On September 20th the ROBERT detached from the Pacific fleet and sailed for home via Subic Bay in Manila, where 59 Canadian former prisoners were picked up and transported home. The ship left Manila on September 29th, just avoiding a typhoon, and sailed for Pearl Harbor, thence to Esquimalt to arrive October 20th. On December 10th, 1945 the ROBERT was paid off and transferred to War Assets Corp. in January, 1946. She had steamed 22,000 miles on this last commission.

The ROBERT has probably steamed more miles, visited more ports and seen more countries than any other ship in the Canadian Navy during the war. It was truly nicknamed the “lucky,” being very vulnerable and travelling great distances in hazardous waters, yet suffering no real mishap.

Webmaster: William G. Hillman

BILL & SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

Copyright 2000/2006/2017

Bill Johnson Material Copyright 1988