109

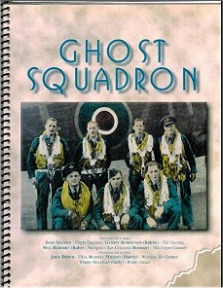

of 150: Ghost Squadron by Garnet A. Robertson

This is an excerpt from Garnet Robertsons

oral history, submitted to the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum as

a 64-page booklet with the title "Ghost Squadron." In the excerpt he talks

about his life prior to World War II on the farm in rural Manitoba northwest

of Brandon, enlistment into the air force and personal stories related

to his time in training with the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

He ultimately completed his training as an Air Gunner and we follow him

up to his assignment to a Whitley aircrew in England. His story is not

detailed in the training process, but is filled with insights of a young

man on the farm adapting to life as an airman in the Royal Canadian Air

Force.

I

was born in Winnipeg on June 12th, 1925 while my folks were living at Grosisle.

My father was the CNR agent there. We moved to Isabella, Manitoba when

I was one year old. I took all my schooling at Isabella, including Grade

XI.

I

was born in Winnipeg on June 12th, 1925 while my folks were living at Grosisle.

My father was the CNR agent there. We moved to Isabella, Manitoba when

I was one year old. I took all my schooling at Isabella, including Grade

XI.

We lived in the CN station. It was in poor shape when

we arrived. The station was heated with a cook stove in the kitchen, a

coal heater in the living room and a coal heater in the waiting room. The

train went through at 5:30 a.m. twice a week and on those mornings it was

fairly warm, as my father stoked up the heaters when he met the train.

The other mornings were very cold. Usually we laid out our clothes at night

so we could get into them as quickly as possible in the morning. After

we were there for a few years, the CN insulated the station and stuccoed

the outside. My father built on a kitchen and put a small basement in with

a coal furnace. Then the building was quite comfortable.

Isabella had a population of about one hundred people.

There was a general store, post office, hardware, blacksmith shop, lumber

yard, two garages and two elevators. The nearest large town was Birtle,

about eighteen miles away. Most of the farmers did their business in Isabella.

There was also a rink with one sheet of curling ice and a skating rink.

This was the main centre of entertainment during the winter months. The

rink was also used in the summer as a livestock barn for the local fair.

During the winter the rink was not open on Sundays, so we kids would go

in through the window and play hockey with a rubber ball so we could not

be heard.

Things were very tough at this time as the depression

was on. No one had any money and most of the older guys could not get a

job. During summer holidays and the fall, I worked on a farm. All of the

work was done with horses as there were very few tractors at that time

and nobody could afford fuel for them. I would get up at 6:00 a.m., feed

and clean five horses, have breakfast, and hitch my outfit to a plow or

cultivator and work until noon. I would have dinner and go back out at

1:00 p.m. then work until sometimes dark. In the fall, I stooked while

the boss cut the grain with a binder and four horses. This was tough work,

but I enjoyed it.

At that time most of the farmers would load their own

grain, usually about 50 or 60 bushels at a time, into the box car. This

was done using a team and wagon. It all had to be loaded by hand and unloaded

by hand. They would get us kids in the box car to shovel the grain to the

back at each end. We would work all day and earn about twenty-five cents

each. It was hard work, but we did not mind. Usually, we had a lot of fun

jumping around in the grain.

My dad kept hackney horses that we showed in the summer

fairs and also at the Brandon winter fair. My brother and I each had a

Shetland pony and we would haul the water for these horses. We also hauled

out the manure and brought in straw for them after school.

When the well in Isabella went dry in the dry years, I

would pick up cream cans around town with my pony and wagon, and haul water

from a farm two and one-half miles away. I would do this every morning

before school. I was paid five cents a can and thought I was really making

money!

My dad used to get his hay hauled from the Birdtail Indian

Reserve, west of Buelah. It was usually Soo Ben who brought it. My mother

would feed him before he started back. All us kids were scared of him because

he was supposed to have been at 'The Little Big Horn.' He would have been

only a baby then and he was an old man when he hauled our hay.

The Indians at this time always left the reserve in the

spring and wandered around the country all summer. They set up their tents

wherever it suited them. They lived off the land and also sold baskets

and mats that they made out of willows. When the Indians came to Isabella,

they used to camp near the nuisance grounds. The horses would be hobbled

so they would not wander too far away, and we kids used to feel sorry for

them. We would sneak up to them and cut their hobbles. Luckily none of

us were ever caught!

My brother and I had to exercise the hackney horses every

night and we had to do it by walking them. We finally told dad that we

were going to ride the horses to exercise them and he agreed as long as

we did not gallop them. We would trot them until we were out of sight of

him and then we would start a race. There was one horse that was not a

very good hackney but it was a real good saddle horse. We decided to make

a jumper out of him and set up a jump in a bluff just north of town. When

we had him really jumping well, we told dad. He was not very happy but

when we showed him what the horse could do, he decided to take him to the

winter fair in Brandon and show him as a jumper. The horse won his class

and dad sold him for a good price.

About this time, my brother and I thought it was time

we took the horses on the fair circuit. We would drive two and lead the

rest behind. We would show in a town one day and drive to the next fair,

often as far as twenty miles away, that night. It was a hard grind but

we enjoyed it and nearly always brought home the first prize and championship

ribbons. There were about five other families from Isabella, showing at

this time. As a result, we had some good times!

It was about this time that I wanted a bicycle. I only

had four dollars. I went to see the hardware man about buying one and it

was going to cost me twenty-six dollars! He agreed to sell the bicycle

to me with the four dollars down and I could pay him whenever I made any

money. It ended up that I was paying him ten cents and twenty-five cents

whenever I earned it. I imagine that he was a happy man when I finally

paid it off!

We had a midget hockey team that was managed by a local

farmer. He used to give us a turkey every year to raffle off in order to

raise money to pay for our uniforms. In the end we were called the turkey

team. We played in the school tournament at Hamiota and though we were

all a lot younger than the rest of the teams, we always gave them a scare.

Our manager liked to imbibe, so we usually played in bigger towns where

there was a beer parlor. We stayed together until about 1942, when a lot

of the guys decided to join up. I went to Brandon and got a job in the

CN express. They used to hook about three express carts together fully

loaded and expected you to pull them out to the train. After a while, I

figured there must be a better way to live than this, so I quit.

I decided to join the air force, but being only seventeen,

I had to have my parent's permission. My dad said he would not give it

to me, but I said that I would go anyway. He finally signed a paper giving

his okay. I enlisted in Winnipeg in the RCAF and was sent to Manning pool

in Brandon. I did not know anyone when I arrived there. We were kept in

quarantine for two weeks and during that time, I met a few guys.

One of them decided that we should go up town, so he borrowed

an "ID" card from one of the fellows who had been there for a while. He

got out and then threw the card up to me and I met him outside. We saluted

everybody in a uniform that night just to be on the safe side.

We were training in the old Brandon arena at that time.

I met some guys that I knew after I had been there a few days. One was

from Arrow River and one was from Beulah. I also met Ray Reid from Isabella.

He was a few classes ahead of me, so he was not around too long. We were

then training at the summer fair grounds.

One day we were doing a lot of marching and it was really

hot. To the guys from Arrow River and Beulah, I suggested that we duck

into the hedge when we were going by and then go up town. We were the last

in line, so we ducked in and hid until the troop got a good ways away and

then we headed up town. We thought that we would really be in for it when

we got back, but we were not even missed!

One Saturday morning we got a bunch of needles (vaccinations)

and then were taken out on the parade square to drill. When the guys started

to pass out left and right, they broke the drill off and gave us the rest

of the weekend off. We were not supposed to leave camp, but a guy from

Decker and I decided to hitch-hike home.

By the time I arrived home, I was really sick. I told

dad that he would have to drive me back first thing in the morning. He

was not too happy about it and took his time getting there, stopping at

my uncle's place in Crandall. It was about 8:00 p.m. that night when I

checked into the doctor's office. He wanted to know why I had not come

in sooner. I sure did not tell him the truth. He checked me over and said

I had the measles and sent me to the hospital at #12 (Service Flying Training

School in Brandon) which is now the Brandon airport. I was really sick

for about three days and then felt fine. They kept me in for two weeks.

When it came time to be discharged, the guy ahead of me, who had been the

doctor's ski instructor at Banff, got two weeks leave. I guess the doctor

thought he had to give me leave because he had given it to the other guy,

so I got one week.

When I got back after leave, I was scheduled to be shipped

out to Vancouver. All the guys I had known were already gone. I caught

the train in Brandon along with about fifty other guys. We had a good trip

out. There were a couple of musicians in the crowd, so it shortened the

trip. When we arrived at Vancouver, we were to take a refresher course

at Vancouver Tech and were to be billeted out in private homes.

I had met a couple of guys on the train so the three of

us boarded at the retired chief of police's home. We went to school from

9:00 a.m. until 4:00 p.m. and had the weekends off. We were there for six

weeks so had a real holiday. The only time we saw an air force personnel

was on payday. The lady where we stayed really used us well, but I think

she likely was glad to see the last of us. We managed to break her daughter's

bed that we were using.

Percy Tinling and I were posted to Quebec City and Hank

Misenheimer was posted to Alberta. It was a seven day train trip from Vancouver

to Quebec City and we spent most of it playing poker. When we got to Regina,

Percy and I were both broke, so I phoned the folks and told them when I

would be going through Brandon. They met the train and we had a short visit.

I put the bite on dad for a few bucks, so Percy and I were back in the

poker game! By the time we got to Winnipeg, we were nearly broke gain.

His folks met him at the train and he bummed some money from them. We lasted

until we got to Montreal.

We laid over in Montreal for a half a day and we got to

see quite a bit of the city. One of the guys on the course and I

each had a dollar and he wanted to go to the house of prostitution. We

matched to see who got the two dollars - and he won. We asked a policeman

the directions and he showed us. Once there we were taken to a room where

six fat and forty women in kimonos were lined up. He told them that he

only had two dollars, so they showed us the door very quickly. That was

one day I was glad that I was broke.

We arrived in Quebec city and were marched to Lower Quebec

where we were billeted in an old orphanage that was six stories high and

had been condemned. We had fire drills day and night the entire time we

were there.

There had been a big fight between the air force and the

local Frenchmen just before we got there, so Lower Quebec was out of bounds

to us. We had to take a direct route to Upper Quebec without stopping at

any of the stores or pubs in Lower Quebec. Tinling and I were on kitchen

fatigue one night and when we got finished we decided to go over the fence

to a pub in Lower Quebec. No one could speak English, but they used us

well. They bought the beer all evening.

The Mess Hall at Quebec was just that, "a mess." The grub

was terrible and the flies were so thick you could hardly walk through

them. It did not seem to bother some of the guys though, as they ate everything

in front of them. One day we were having spaghetti and the ceiling was

covered with fly stickers. The guy across from me was wolfing down the

spaghetti and pushing the flies, that had fallen from the fly stickers,

to the side of his plate. I ate most of my meals in the canteen.

Bob Carnegie, the guy from Beulah that I was in Brandon

with, played the bagpipes. One night I heard them being played a couple

of floors above me and I figured it must be him. He had just arrived and

was a couple of classes behind me. We had a good visit. He was later killed

over Germany.

For the most part we did studying at Quebec City plus

a lot of drill. We also did some machine gun training on old World War

I Vickers machine guns. We graduated from Quebec as LAC's and were then

able to wear our white air crew ribbon in our caps. We thought that we

were really something!

After graduation, a bunch of us went to the Legion in

Upper Quebec for a party. You could get quart bottles of Black Horse beer

really cheap, so we tied a good one on; me especially. The guys had to

get a cab home as I could not walk. When we got to the gate, the CO was

just coming out. The guys tried to get me walking and told me to be quiet

as the CO was coming. I said F--- the CO. All he said was "Get him to bed,

boys."

The next day we left for Mont Joli, Quebec and boy was

I sick. Tinling brought me a couple of pints of milk and it got me

on my feet. Mont Joli was a modern airport, but miles from anywhere. We

had lots of time to study as there was nothing else to do except play basketball.

A few of us went into the town of Mont Joli one night, but the people did

not use us well. You would have thought we were in Germany.

We started our flying at Mont Joli and flew in Fairy Battles.

They had been used in the evacuation of Dunkirk so were not in the best

of shape. Two gunners would go up two at a time. One gunner in the turret

and one sitting on the floor near the engine cooler. You would get the

fumes from the engine and would usually come down feeling lousy. One plane

would fly along with us towing a 'drough' (drogue) which was a canvas affair

something like a parachute. We shot so many rounds at it and they would

count the holes when we landed to see how we had done. Sometimes our own

plane would pull the drough. We got smart and started pulling it up close

behind the plane. We got a much better score this way!

We used to be trucked away up the Coast of the St. Lawrence

to a gunnery range for all kinds of gunnery training such as machine guns,

rifles, pistols, and skeet shooting. These were long cold days as it was

October and November. There was no place to get warm because everything

was outside. We trained on aircraft recognition, fighter affiliation, how

to unassemble a machine gun and re-assemble it in so many seconds blindfolded.

We would be up at 6:00 a.m., have breakfast, train until

noon, have dinner and be back training at 1:00 p.m. We would break for

a physical training class at 5:00 p.m. and have supper at 6:00 p.m. Sometimes

after supper we would play poker, but we usually studied until about 9:00

p.m. and then went to bed.

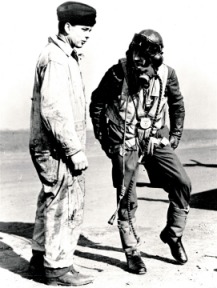

We had airmen from England, Australia, New Zealand, United

States and Poland. We finally graduated as SGT. Air Gunners. It was a great

day when we finally got our Air Gunners Wing and Stripes. It really felt

worthwhile when your name was called out and you had your wings pinned

on by the CO.

Al Patterson, who had the bunk above me, was held back

because he was having trouble with his eyes. He sewed my SGT. stripes on

my 'Great Coat' for me. When I later became a Warrant Officer and removed

my stripes, I found a note that he had sewn under them. "Good Luck Robby."-

Al. He graduated a couple of weeks later and was eventually killed over

Germany.

We were given a months embarkation leave after graduation.

Another gunner and I decided to fly home from Montreal to Winnipeg to give

us more time at home. We left Montreal at 11:00 p.m. at night on a Trans

Canada Airline "Hudson" which was the top airline plane at that time. It

carried twelve passengers, a pilot and a co-pilot plus a stewardess who

also had to be a nurse. The pilot invited us to come up to the cockpit

and he showed us how everything worked. We felt quite honored. We arrived

in Winnipeg at 7:00 a.m. after stops in North Bay and Fort William. (now

Thunder Bay).

I finished 23rd out of a class of 142 at Mont Joli, so

I did not think that was too bad. We had a lot of washed out pilots and

navigators on our course who were a lot smarter than I was.

I arrived home in December for my leave, so I managed

to get a few hockey games in. I saw quite a lot of Della, and I was also

home for Christmas so that was nice. When my leave was up, I was sent to

Lachine, Quebec to wait for a ship. I arrived a few days after the rest

of my group and most of them had already been shipped out. It meant making

all new friends. The ship named "Louis Pasteur" arrived in Halifax with

a load of German prisoners of war. It was lousy so it had to be fumigated

before the return trip. We were supposed to go on it, but were changed

to the "Il De France." We were all happy as it was a much better ship.

We left Lachine for Halifax around the 5th of February,

1944, On the train trip down when we were going through the Gaspe area,

we had bricks thrown through the train windows. It made us wonder if we

should have been staying home and doing some cleaning up in Canada.

As soon as we arrived in Halifax, we were marched directly

onto the ship. They had taken all the furniture off the ship and each room

was full of six bunk beds. There were about twenty-five of us in each room.

The bunks were so close together, you could barely turn over. We were each

assigned a job to do on the trip over. Some of the gunners volunteered

for gunnery helper. This meant they were with a navy gunner on the cannon

station. These guns protruded out from the deck of the ship and had little

protection from the wind and spray from the waves.

We had a very rough trip over, so these guys had it really

rough. We were on duty for four hours on and four hours off. I was assigned

as a guard on the theater door. I don't know if there was a theater or

not as I never showed up. Nobody came looking for me, so I had a relatively

easy trip.

The mess hall had one long table which had buns and tea

on it. We went through in file and had our mess tins filled by navy cooks.

There was a barrel at the end of the table to but garbage into and quite

often that is where my meals ended up. Usually I ended up with tea and

a bun.

We were a fairly fast ship, so we had no convoy and we

were sailing alone. We had a couple of submarine scares, but nothing came

of it. It took us nine days to cross and I was really happy when I saw

Greenwich show up in Scotland. The Bay was too shallow to take the ship

right to Port so we were taken ashore by barge. We were loaded on a troop

train at Glasgow and taken to the south of England, to Bournmouth. We saw

from one end of the British Isles to the other on the first day. Bournmouth

was a resort city before the war and had been a beautiful place. All the

hotels had been taken over by the air force and stripped. All the rooms

had steel bunk beds in them. They were still quite comfortable though.

We did a bit of training there, but it was mostly just waiting to be posted.

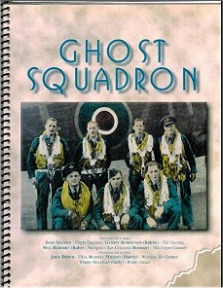

The postings finally came through and I was posted to

Honeybome. Honeybome was a flight station and they flew Whitleys. These

were a four engine plane with just a tail turret, no mid-upper. These planes

flew very slowly and flew with the nose appearing slanted downward. All

types of crew were sent here except flight engineers. This is where we

crewed up. Most of the gunners knew each other so they paired off. I was

again the only one from my old course and as a result I did now know anyone.

Johnny Dench, a pilot and "Boomer" Colins, a gunner, were

both officers and they had gotten together. Terry Sullivan, a bomb aimer,

Neil Rubbery, a navigator and "Shorty" Wright, a wireless operator were

like me and did not know anyone else on the station. Dench asked us if

we wanted to fly with him. We all agreed so we had our crew. Boomer wanted

the mid-upper turret and that suited me as I wanted the tail turret.

Grain elevators at Isabella Manitoba. :: CNR station

at Mont Joli Quebec.

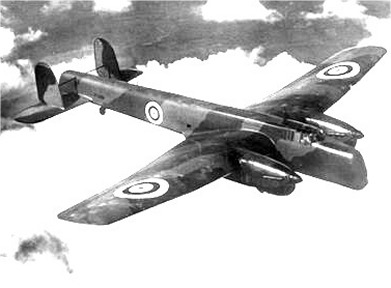

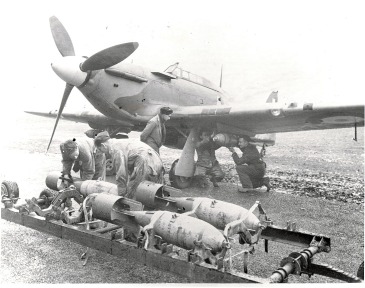

Armstrong Whitworth Whitley aircraft Wikipedia :: Airmen installing

Browning machine gun in rear turret of a Whitley aircraft.

110

of 150: They Toil Without Glory

Broadcast on the BBC's Short Wave

Overseas Service (Reprinted from Wings Over Borden, newsletter of No. 1

SFTS Camp Borden, November 1942).

I would like to talk to you about those four simple words

-- and all they imply in the Air Force here, in Canada, in the United States

of America and everywhere. To us in the Air Force, they perhaps, have a

meaning that others do not see. To us, they are symbolic of men who have

done much to make the Air Force what it is today.

Without them; we should fail. Without them, the Battle

of Britain would have been lost, Without them, (and I say this deliberately)

this mighty island might, long since, been battered to its knees.

But thank God we had them. They (no less than the men

in the air) helped send the Luftwaffe back into Germany to lick its

wounds... they (no less than the men in the air) made it impossible for

flames to roar over this Island as they did over London more than fifteen

months ago.

I pay tribute to the men of the ground crews -- the riggers;

the engine mechanics; the cooks; the radio operators; the armourers; the

clerks; the equipment assistants; the transport drivers; the instrument

makers; the parachute riggers -- all that host of people in Air Force uniform

who are among the fifty ground crew trades that we have today.

The air crew -- the men who fly, the valiant young men

before whose sheer, stark courage I always feel humble, when I see them

off on a raid -- they are gallant company. I would take away from them

no whit of the credit they so rightly deserve. But I would ask you to remember

that an air force is a team -- a team in which each section is interdependent

on the other. Those gallant young men who run interference for them and

make their spectacular gains possible. Few of the ground crew are youngsters.

Those who are, you can take my word for it, would be in the air if they

could follow their own desire.

Many of the ground crew are long past the age when Air

Force service means high adventure, travel, a chance to see new things.

You reach an age, you know, when you like to come home

in the evening after your day's work is done; and, depending on your walk

of life, take off your shoes and put on slippers, loosen your collar (so

to speak) and spend a quiet evening with your wife and children. Many of

those ground crew have reached this age. They held good jobs in peace time.

There were many foremen mechanics among them. The majority were already

skilled tradesmen.

But they had in them that love of fair play -- that hatred

of the bully that characterizes our people wherever you find them. They

tossed aside their good jobs. They accepted the lowest rate of pay in the

Royal Canadian Air Force. They exchanged the comforts of home life for

a life in huts. They bade their wives and children goodbye, and headed

out for a future in which everything was uncertain.

But perhaps lm going too far when I say that everything

was uncertain -- that (as ground crew) their lot would be "Toil Without

Glory."

There are several definitions for the word "toil." But

the one that I feel most properly describes it, is the one that says toil

"is hard and unremitting work.'' That is true, very true!

I would like to add to that definition. In addition to

being hard and unremitting work, the toil of ground crew, in the Air Force,

is vital work. It is war work that means the difference between life and

death to the men who fly the aircraft.

Let us look at these ground crew for a few minutes and

I will try to let you see them as I see them. On one of our stations there's

a man called Paddy. Paddy is the sort of man youd pass in the street and

never notice him. Paddy is forty-seven years old and (if you could get

him to talk about it) he would tell you of a dirty night; near Amiens;

in another war, long years ago. He brought back a souvenir from that war

-- a jagged one that the surgeons dug out of his shoulder. When this war

came along, Paddy enlisted again. He knew he was too old for active service.

But he also knew that he was a first-rate cook.

Paddy is up there in the Midlands with one of our Canadian

Squadrons. Just about now (and it is just about two Oclock in the morning

here in London) Paddy is likely busy over his pots and pans (on the nights

our aircraft are on operations). Paddy knows what it means to keep the

fire going all night long. He knows too, just what an important effect

bacon and eggs, if he can get them, have on morale when he serves them

to tousle-headed crews at all hours of the day and night.

Away to the north of the aerodrome is another. The wind

never seems to die down there. In the winter it howls from the north and

brings on its frozen breath that hard, stinging sleet that numbs the fingers

and chills the marrow. There are fine Canadian boys flying the aircraft

from that station. They battle with sleet and hail and wind long before

(and long after) they've battled the enemy. But they can only do that because

of a group of ground crew men, whose names never strike the headlines.

Where the cruel wind howls and bites like a mad dog, these

men work. Though their fingers are blue with cold, though their clothes

are stiff with frozen rain, they swarm over the aircraft, cleaning, tightening,

adjusting, fitting; with almost loving care.

I would like to tell you about the radio mechanics. You

don't hear much about them: more because the job they do is one of the

things we don't talk about. They are highly skilled men. They are doing

a job that has much to do with the successful defence of this island. But

no glamour surrounds them. They are hidden away, many of them, in isolated

areas. They do not have the fellowship of the mess. They sleep at odd hours.

But they do their job magnificently. They take great pride in it. They

know its importance. They know that, each day, they have done something

to help to win the war. In that knowledge they are happy They are well

content.

Let me take you to a fighter station during the season

when cross-channel sweeps are being made.

On the days when these are at their height, the squadrons

take off three or four times. That means heavy work for the ground crews.

It means constant

and careful checking of engine and airframe. But these

men do not complain. If the aircraft they service are in action it is

their fight. If their pilot does a victory roll as he comes in to a landing

it is their victory.

They have a peculiar sense of possession. It is their

aircraft -- their pilot -- their crew their war their victory.

Let me tell you of another incident. Recently, one of

our bomber squadrons was converted from twin-engine bombers to heavy, four-engined

types. The aircrew had made the change in record time -- just half the

time previously taken by any other squadron.

They completed their conversion a very few days before

the first thousand bomber raid on Cologne. But while the aircrew was completing

its job, the ground crew had accomplished an even greater task. Faced with

new aircraft where there were hundreds of minor additions and modifications

to be made. Fitters. riggers, engine mechanics, armourers, even clerks,

all turned in. They worked night and day. They had as little as four hours'

sleep one night. At times there were as many as thirty men working on one

aircraft. But, when the Commander-In-Chief gave the order that sent another

thousand bombers into the air; THAT squadron was ready. It sent out the

largest number of aircraft it had ever done. It dropped four times the

weight of bombs that it had ever dropped. Every aircraft functioned perfectly.

You didn't read about those ground crew in the stories

that were headlined all over the world because: THEY TOIL WITHOUT GLORY.

But the men who flew the giant bombers knew what THEY had done. They did

not spare their praise. And I can tell you, the Wing Commander of that

squadron knows that he has the finest ground crew now serving the British

Isles. They serve with little praise; no medals; no glory. Yet there is

bravery where chance it fails.

Take for instance, the bravery of Flight Sergeant Lummis

who was working with gasoline in a hangar at Trenton, Ontario. Suddenly,

a full can of gasoline burst into flame. Calmly, Flight Sergeant Lummis

carried it towards the doors of the hangar. Ahead of him was the expanse

of the aerodrome; behind him, a hangar crammed with precious aircraft.

The heat was intense; and Lummis, his hands and face burned, was forced

to set down his blazing load. For an instant he looked back -- saw that

hanger filled with valuable planes. Again he picked it up, the searing

hot flames licking over his face and chest, blistering his hands, and carried

It hundreds of feet beyond the hangar -- to safety. He nearly lost his

life, but he saved many priceless aircraft. In time, Flight Sergeant Lummis

was awarded the George Medal and remember, decorations are hard to get

in Canada.

This is the hour -- (as I told you, it is two o'clock

in the morning here) at which our bombers may be expected to arrive over

the spot; in Germany, which has been designated; target for tonight.

At this very moment, German people may be dashing madly

to the shelters as more than one thousand aircraft sound over their heads.

Their night may be made hideous with the shriek of descending bombs; the

bursting of incendiaries; the explosions of anti-aircraft batteries.

And if (at this very moment) a German war factory is disintegrating

under the weight of heavy bombs; if a submarine base is heaving from its

foundations; -- give praise to the flying crew certainly. But save a few

or more than a few -- of your words of praise for the ground crew the

men who make such gigantic raids possible.

Save some of your cheers for THEM.

Each time you read in your papers of a bombing attack;

or of a vicious fighter battle; or the sinking of a submarine, remember

the ground crew. Each time I leave an air station (usually at night) my

heart goes out to these men; to whom I now pay tribute.

Let me assure their relatives that their efforts to win

this war are as important as any other. They shall not go unrecognized.

Let your prayers be for them too, for in so doing, you pray for the safety

of them that fly. The ground crew pursue a noble calling and: THEY

TOIL WITHOUT GLORY

I

was born in Winnipeg on June 12th, 1925 while my folks were living at Grosisle.

My father was the CNR agent there. We moved to Isabella, Manitoba when

I was one year old. I took all my schooling at Isabella, including Grade

XI.

I

was born in Winnipeg on June 12th, 1925 while my folks were living at Grosisle.

My father was the CNR agent there. We moved to Isabella, Manitoba when

I was one year old. I took all my schooling at Isabella, including Grade

XI.