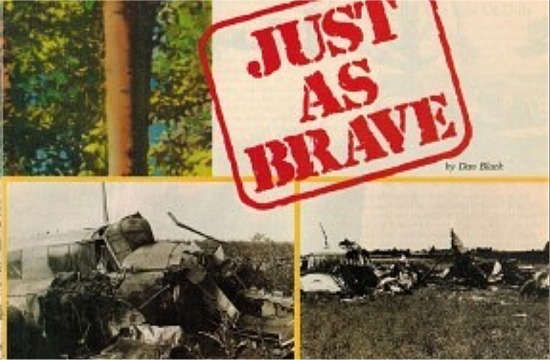

Strapped to the rear seat of bright yellow Harvard

3209, pilot instructor John Sweet felt like the number two man on a horse:

He was aboard, but for the moment control was in the hands of student pilot

Ken Child up front.

It was January, 1944, and the two were returning to base

at Aylmer after a day spent with other trainees flying target practice

over the flat, snow- covered farmland of southwestern Ontario. Unknown

to either airman, disaster was about to strike.

"We were four to five miles from base and went into a

dive to drop to 1,000 feet, and I remember looking over to my right and

seeing (Harvard) FE662 trying to fly formation," Sweet recalls. "I don't

know why he did that, but there we were 30 feet apart and low on fuel."

Seconds later, the other plane disappeared, "but as we turned into the

wind on our landing approach, he came out of the blue and went through

our wing. All that remained was three-quarters of a wing. We were upside

down."

British student pilot Peter Stratton was decapitated as

FE662 slammed nose first into the airfield 750 feet below. His Canadian

instructor, Reg Scevoir, had the flesh ripped from his face and required

extensive reconstructive surgery. The Harvard's 575 h.p. engine drove into

the frozen ground as the rest of the plane ripped free and landed 50 yards

away.

Still upside down, 3209 was losing altitude. Rescuers

ran to what remained of FE662, while others watched in horror, then

relief, as Sweet fought with the controls and righted his aircraft. "I

don't know what went through my mind," recalls the former instructor, now

70. "For the longest time, I had trouble remembering anything after or

before the crash."

When 3209 came down in a field behind a hangar it was

doing 200 m.p.h. Normal approach speed is 110. "We lost our right wheel

and headed toward the road," Sweet recalls. "I couldn't make the runway.

Nothing was said. It happened so fast."

Ripping up chunks of earth and grass, 3209 punched through

a road fence, taking out eight posts before hitting the first ditch where

it lost the left wheel. After skidding across the ·road, the nose

of the plane slammed into the next ditch, before taking out another fence

and sliding 80 feet into a field. Fortunately, the Harvard's fuel tanks,

located near the rear seat, were almost empty. Sweet was pulled unconscious

from the burning wreck with a rope tied to a crash truck boom. He had a

broken arm, broken left leg and a gaping hole in the front of his skull.

His hospital treatment would last a year and include psychiatric examination.

Ken Child came away with a broken left arm.

''A person can ask me today if being an instructor in

Canada during the war was dangerous," Sweet says. "You bet it was." All

volunteers who had freely offered their lives to serve Canada during WW

II, most, if not all of the men who served at No. 14 Service Flying Training

School under the wartime British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP),

wanted to go overseas. Sweet himself enlisted in 1942, and before advanced

training at Aylmer passed through Manning Pool No. 1 in Toronto, initial

training school and elementary flying training school on Tiger Moths, in

Oshawa.

After receiving his wings in Aylmer, Sweet could have

gone to Bagotville, Que., and then overseas. Instead, he was assigned to

Trenton, Ont., for pilot instructor training. "Once you went to Trenton,

you were stuck," he says. "There was no way out.

You were going to be an instructor." Sweet recalls a lot

of men purposely gave the wrong answers on their written instructor's tests,

hoping they'd fail and be reassigned overseas. "But the teachers at Trenton

were wise to this. They knew who was trying to fail. They knew the guys

had the right answers in their heads, if not on paper."

The service flying training school was the student's introduction

to heavy, high performance WW II aircraft-in particular the Harvard, and

adds Sweet, those in his charge weren't all choirboys. "You'd have to knock

the overconfidence out of them during the first month, “he says." It took

the next month to teach them about flying, and in that month they learned

so much they were scared to fly in the third month. Sometimes you'd have

to go looking for them."

Instructors prepared students for the worst conditions,

allowing them to learn from potentially fatal mistakes. The risk was understood.

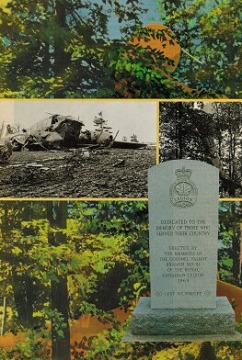

Says Harry Saelens of the Tillsonburg, Ont., Branch: "It doesn't matter

whether you're pranging in a Tiger Moth over Neepawa or in a Halifax over

Berlin, you're just as dead." Mute evidence of the truth of that

statement was found in the small cemeteries that dotted the countryside.

Canada only servicemen would eventually comprise 10 per cent of the 44,000

Canadians killed in WW II. "These young fellows were just as loyal just

as courageous, just as young and just as prepared to go and do those big

and glorious deeds as those who got to do them, but they never got the

chance and they got none of the rewards. Nobody ever talks about them any

more and I think they should," says Saelens.

Pilots and instructors weren't the only ones at risk.

John French, 67, of Langton, Ont., was an airframe mechanic based in Yorkton,

Sask. He recalls one close call while flying as a passenger in a Cessna.

"It started to snow heavily and we got down to 50 to 60 feet off the ground

to spot the lights of a town or village . The pilot followed a railway

line, figuring we'd come across a grain elevator with the name of the town

on it. We spotted an elevator, but while making a pass we barely missed

a water tower. We felt awfully lucky."

Before moving to Kingston, Ont., in August 1944 -- where

it operated for another year -- No. 14 Service Flying Training School enjoyed

three productive years at Aylmer with 4,144 pilots earning their wings.

The school had an excellent safety record considering the high-pressure

training.

But by 1944, there were up to 500 landings a day and accidents

were inevitable. During its four years of operations, including the time

in Kingston, 26 fatal crashes killed 12 instructors and 26 students.

Overseas, a tour of operations called for 300 hours flying

before a leave was granted. "Back here in Canada," says Sweet, "an instructor

would have close to 2,000 hours. He'd be flying the seat of his pants off

to keep his students up on their time."

The diary from No. 14 describes forced landings, nose-ups,

ground loops, bent air screws, collisions with trees and even a Harvard's

run-in with an outhouse. "A dense ground fog closed in with 13 aircraft

away from the field," notes a booklet by M.L. Mcintyre. "One found its

way back, 10 landed at London, one was forced down near London and one

force-landed near some cottages at Port Bruce on Lake Erie.

The plane was undamaged, but in the attempt to fly out,

an instructor had the misfortune to hit an outhouse on his takeoff run.

Luckily the outhouse was unoccupied and its damage appears to have been

slight.

With planes buzzing overhead-some occasionally crashing

in farmer's fields the war arrived in Aylmer as it did in other towns with

a training base. Newspaper accounts tell of practice bombs crashing

through greenhouses and bullets dropping from the sky. A March i7, 1943,

story in the St. Thomas Times-Journal describes how Mrs. A.S. Taylor, of

Port Stanley, had a narrow escape when a .303 bullet tore through the roof

of her kitchen, grazed her left arm below the elbow and then bounced onto

a breakfast plate.

But despite narrow escapes for civilians and military

personnel, communities were proud of their training bases. Students and

instructors were invited into private homes for Thanksgiving dinner

and other celebrations.

Romances blossomed and the towns' economies grew. It was

a sad day when a base closed. "No. 14 brought the war very close to home,"

says Aylmer high school history teacher Kirk Barons. "It made the war very

real for this community and if you compare the small number of fatal accidents

that happened in this area last year to the number that occurred back then,

you can recognize the element of danger that existed.''

Former flying instructor Archie Londry, 66, a service

officer with Gen. Hugh Dyer Branch in Minnedosa, Man., recalls working

on a broken radio receiver in the back of an Anson one night. About 30

miles from Brandon and at an altitude of 3,000 feet they ran into a severe

ice storm with lightning. The starboard engine kicked out. ''We had to

maintain our flying speed to avoid a complete stall," recalls Londry, who

took control of the training aircraft.

The lightning helped Londry spot a small slough, which

cushioned the plane before it crashed into a bush, losing its wings. There

were no injuries, but the crash marked one of many close calls for

the instructor, whose room-mate, also an instructor, died in a mid-air

collision between two Cessna Cranes. "The students didn't learn by you

telling them the mistakes," he says. "You had to go as far as you could

go and let them make and see the mistake and then show them how to recover.

It was a necessary part of training and it's how the majority of

accidents happened."

Saelens says that, as host of the BCATP, Canada trained

125,000 men from all over the Commonwealth, including 50,000 pilots. During

the five years it operated, more than 800 trainees died. "In my army

service I never knew of anyone being killed, but it did happen," he says.

"Navy men drowned during training, but the largest losses were suffered

by the air force .''

"People are just beginning to realize what the training

casualties were," adds Londry. "Forty five years ago people didn't talk

about it because they were preoccupied with the war effort. But the sacrifices

were made here as well as overseas. From my graduating class alone, about

the same number of graduates died in Canada-only service as those

who died overseas.''

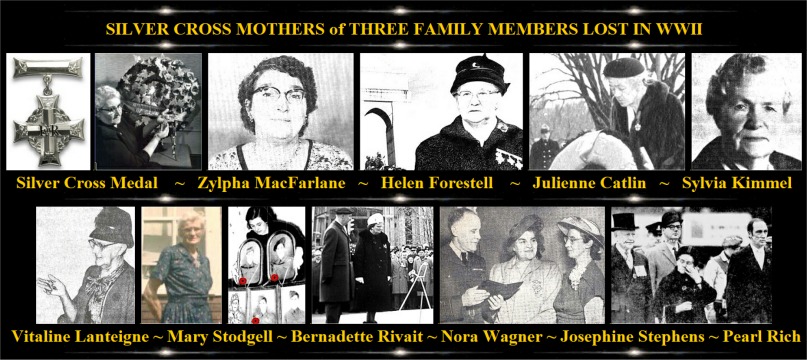

132

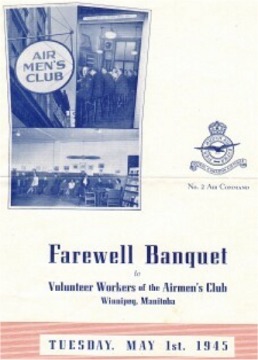

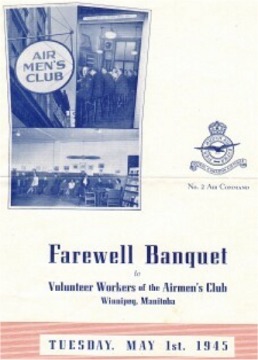

of 150: Winnipeg Women's Auxiliary Air Force - Airmen's Club

"What did we do for them? Found

homes with kind people. Soon their longing for home faded away only to

return when they were on their way home. Many boys who failed as Pilots,

had to be comforted. We sewed stripes and wings on by the hundreds, darned

sox, mended uniforms. Listened to their love stories, looked at hundreds

of photographs of their wives, babies and sweethearts, and we loved it

all. Many times our laughter was very close to tears. We were like a big

family, our own Canadian boys and others from all over the world.'"

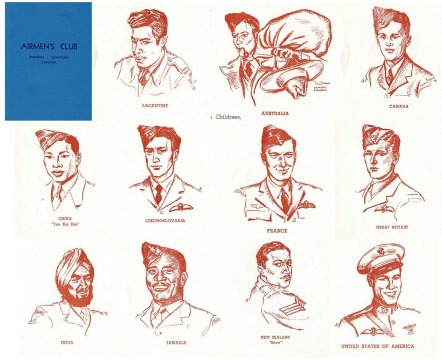

The Airman’s Club booklet featured in this Vignette

was produced for volunteers, friends and airmen and airwomen at the end

of World War II as a memento of the club which was soon to be closed. It

was one of many programs offered by the Winnipeg Women’s Auxiliary Air

Force, a determined group of voluteers making a difference for thousands

of civilians and service personnel wrapped up in the war. It is a remarkable

story which chronicles how amazingly far people were willing to go to help

others during `this darkest hour.’

AIRMEN'S CLUB ~ 1941 to 1945

WITH THE OPENING of the Empire Air Training Stations in the

vicinity of Winnipeg, and the arrival of so many young Airmen from Overseas

it was soon obvious that some place should be available for these boys

to meet and make friends with us. And so, the Airmen's Club opened January

18th, 1941.

THE OBJECT OF THE CLUB was not only to have a meeting

place and a small Snack Bar, but more important to place these boys in

private homes for their "Leave." In this way they would become acquainted

with Canadian Life, and at the same time have pleasant homey surroundings

for their furlough.

The response to our appeal for people who would like to

entertain these young men in their homes was overwhelming. The boys were

from all over the world, of many races and creeds, and, without exception,

they were all entertained in private homes. In the past four years 39,732

have been placed.

All work in connection with the Club was voluntary, members

of the Winnipeg Women's Air Force Auxiliary comprised our personnel.

Shortly after we opened, the U.T. (under training} Pilots,

for the first Royal Air Force Station to open in this Command, viz., Carberry,

arrived. The Ground Crew for this station having arrived in early December,

1940.

Who will ever forget that morning, forty below zero! But

the boys said the warmth of our welcome soon made them forget the cold

weather. Many of us had the pleasure of entertaining these boys in

our homes for Christmas and New Year's Leave and, although the Club was

not open we had already started what was later to be called the "Placement

Desk."

The first Australians and New Zealanders arrived in February,

1941. They were met at the railway station by the Auxiliary's Station Reception

Committee, and brought by bus to the Club, where they were served light

refreshments before they proceeded to their Station. We will always remember

these boys, and the Maoris who came with the New Zealanders.

Boys still kept arriving from Overseas but in the early

spring came many from the United States. At one time we thought of the

United States as "Texas" as so many American boys seemed to come from there.

However, by early summer, boys from every State in the Union were arriving

to enlist in the Royal Canadian Air Force, and some 700 registered at the

Club.

Those boys from Texas who will ever forget them? "Tex"

from Odessa, "E.L." from Houston, Johnny who hitch-hiked 1,500 miles from

Childress, and others too numerous to mention. We placed many of these

boys in private homes, until they were taken into the Air Force and

were posted. We have many letters from these boys, who, shortly after Pearl

Harbour transferred to the United States Air Corps. It was these delightful

Texans who suggested that the Snack Bar should provide something

a little more substantial than sandwiches. And the fact that we were having

more boys every day, led to us enlarging the Club. Three more rooms were

added, including a much needed Canteen.

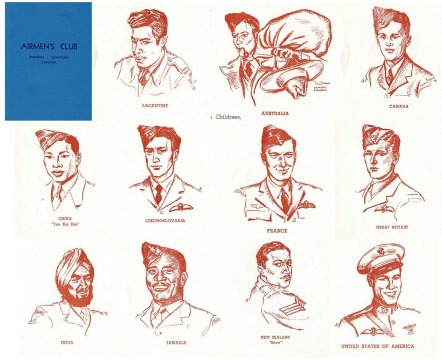

About this time, we began to notice the names of different

countries on the shoulder badges worn. Young men from all over the world-France,

Belgium, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Holland and Denmark, many of these boys

having escaped from occupied territory. We tried to place them with

people from their homeland, and in some small measure bring comfort to

these boys, who in many instances did not know what had happened to their

dear ones.

Boys from British Honduras, British Guiana, Trinidad,

Barbados, Jamaica and the Bahamas, also arrived about this time, as well

as several South Africans. The insignia B.L.A.V. on shoulder badges puzzled

us for a time, but on inquiry we found these boys came from South America.

It meant "British Latin America Volunteer" and was worn by those from the

Argentine, Brazil, Bolivia, Columbia and Paraguay. Some of the boys were

native to those countries, but the majority were British.

Our Club had indeed become cosmopolitan, Canadians rubbing

shoulders with boys from all over the world. We had thirteen boys who came

direct to Canada from Singapore, among them was a Chinese boy named Tan

Kai Hai. According to the "London Times" he was the first Chinese Pilot

in the Royal Air Force, of the others nine were Englishmen, two Danes,

and Tullah, a native of Johore.

Our boys from India: The first one we had was David who

was with the R.A.F. but later there were the boys of the Royal India Air

Force. Our most picturesque guest from India, with his airforce blue puggree

or turban, his short black beard, and about six feet tall, was nineteen-year-old

Sandhu of Pakho Pur. Sandhu was a Sikh. The darling of our hearts was Gopi

from Tranvencour, southern India, who was with us so long at Deer Lodge

Hospital, having had a very bad crash which necessitated many operations.

Gopi received his wings a short time ago, and once again our prayers were

answered.

Among the Maoris was "Snow" whose real name was Kereama,

of Marton, New Zealand. Many of these Maoris had beautiful voices, and

we volunteers will never forget the evening we listened to Maori songs,

sung in the Canteen by three of these boys.

There are many stories to be told, some full of humour

and others full of pathos. The very young boys homesick, and finding everything

strange in our Country. What did we do for them? Found homes with kind

people. Soon their longing for home faded away only to return when they

were on their way home. Many boys who failed as Pilots, had to be comforted.

We sewed stripes and wings on by the hundreds, darned sox, mended uniforms,

listened to their love stories, looked at hundreds of photographs of their

wives, babies and sweethearts, and we loved it all. Many times our laughter

was very close to tears. We were like a big family, our own Canadian boys

and others from all over the world.

How did we entertain our big family? Always they were

encouraged to accept the hospitality of private homes. Concerts and dances

were given at the Club, where the Junior Hostesses from the Auxiliary helped

to entertain. Parties were given for newly arrived trainees, who were to

be stationed in and around Winnipeg, for boys who were passing through

and would be here only a few hours, and there was the night we entertained

289 Sergeant Pilots, of the Royal Australian Air Force, and Gracie Fields

sang to them after her concert at the Auditorium, coming from there with

His Honour, the Lieutenant Governor and Mrs. McWilliams. That was a gala

night for all of us. We volunteers enjoyed the parties as much as the guests.

Our first Christmas party in the big lounge is a happy

memory. Christmas dinner was served to over 200 boys from all over the

world, meetings of old school friends and friends, they had left behind

in England. The boys were all very interested in our guests from Singapore,

especially the Australians and New Zealanders, as many had hopes of

being sent to the Far East, and especially to Singapore, where countless

numbers of their countrymen were stationed during 1941.

The busiest place in the Club was the Canteen. We had

seating capacity for twenty-four. Breakfast, dinner and supper were served.

During the week we averaged around 200 meals a day but on week-ends,

which began on Friday, when trainees as well as Station Staff arrived on

Leave, we served anywhere from twelve to fifteen hundred. Bacon and eggs

were in great demand and thirty to forty dozen eggs cooked in an evening

soon became routine. How the volunteers in the Canteen did this, no one

will ever know, but it was done, and on a four ring gas stove with oven.

Finally, the Winnipeg Electric Company took pity on us, and built us a

six ring stove. And a kind friend gave us a steam table. Then we went to

town! No request of the boys, were they Canadian, American or from

across the Sea, was too much trouble for the volunteers who cooked for

them. 596,879 boys were served in the Canteen during the last four years.

We were the first Airmen's Club in Canada. All work was

done voluntarily and we all had the same idea in our minds, to make this

a home from home, and not just a Canteen. The boys watched us do the cooking

as they had watched their Mothers in their own homes. They helped us wash

dishes, peel potatoes, and in fact did everything but the cooking. Indeed

many the bowl and spoon were licked after the cake was iced.

The expenses of the Club were not carried by the Canteen.

When, by any chance we were on the right side of the ledger, we had

chicken or turkey for Sunday dinner. Never did we hear the song "A Wing

and a Prayer" without thinking of our Club. We had many interested friends,

and they always seemed to be on our doorstep when anything was needed.

Our donations every year exceeded our losses.

Not many people know that the Airmen's Club of Winnipeg

is called by the boys far and wide as the "World's Most Famous Club." And

perhaps with good reason, for our boys are all over the world. Letters

and messages come from Canadians, who have never been in the Club (but

who come from in and around Winnipeg) and they tell of meeting Indian boys

in India who speak to them of the Airmen's Club, Australians and New Zealanders

who meet our boys in Italy and the middle East who speak of us. It would

not surprise us at all to learn someday, that we were known by the underground

of all occupied countries in Europe.

Our volunteers, be it Placement, Canteen or Housework,

gave many hours of untiring service. Many of the Canteen shifts are still

working together in 1945. We do not need thanks. The hundreds of letters

from our boys are enough. One, received from David Kumar (Viiendra Kumar)

our first Indian Airman expresses the finest thanks which could be given:

"Believe me, a club like yours does more to bring International

Friendship together than all the Leagues of Nations in the world."

This outline of the activities of the Airmen's Club is

prepared as a souvenir for all those, whose work made the Club possible.

Chairman ~ Winnipeg, Manitoba ~ April 30th, 1945.

Click for full size

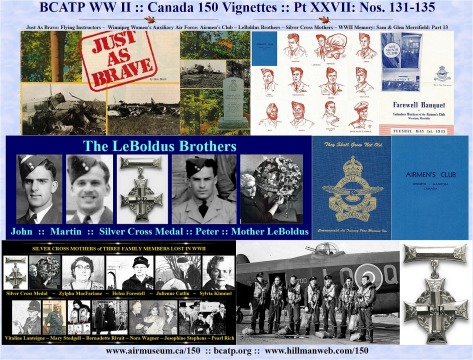

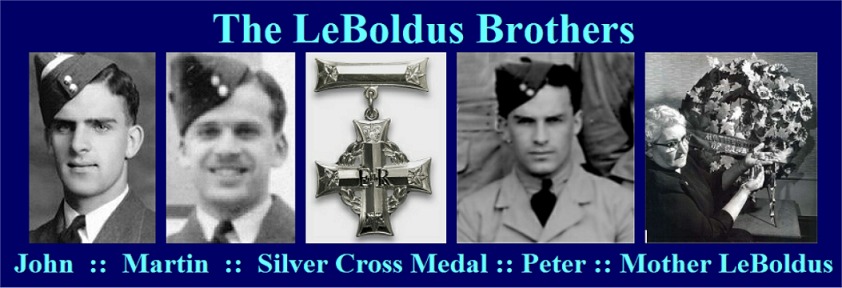

Official

RCAF reports, as documented in the Commonwealth Air Training Museum

memorial book, "They Shall Grow Not Old" can be seen on the left. Additional

information about each of the brothers can be seen below.

Official

RCAF reports, as documented in the Commonwealth Air Training Museum

memorial book, "They Shall Grow Not Old" can be seen on the left. Additional

information about each of the brothers can be seen below.