138

of 150: Passing Muster

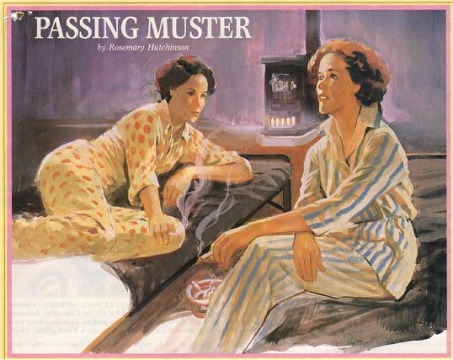

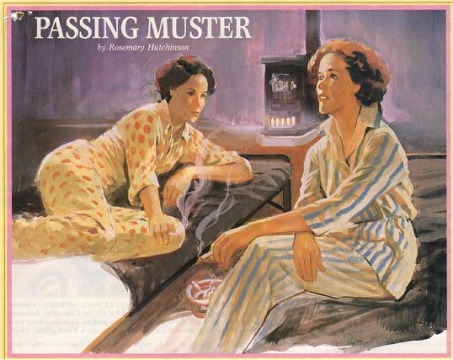

Passing Muster

By Rosemarie Hutchinson

Legion Magazine, July 1986

I lean against the hangar wall and watch the action on the

tarmac. It is crowded with air force other ranks. Soon all this blue-clad

humanity will be dragooned into orderly flights by harassed NCOs. This

is going to be the absolutely ultimate parade. The Kind is coming, the

Queen too, and as an added attraction the two princesses. It is the year

of Our War 1944. The place RCAF Topcliffe, Yorkshire, England.

Though it was six months ago, it seems only yesterday

that I said farewell to my good parents in Canada. I can still hear my

mother shouting instruction: ``When you are on the ship, Rosemary, be sure

to walk round the deck 10 times everyday. There is nothing like fresh air

to prevent sea-sickness!’’ She should know, the sight of a row-boat makes

her throw up, a rubber duck in the bath-tub brings on a convulsion.

About

the first person I had seen on boarding the Queen Elizabeth was my friend

Charlie. I should have known that was inevitable. She and I seem fated

to spend our service life in harness. We have already done 18 months together

as motor-transport drivers in Newfoundland. But I was glad to see her.

Life with Charlie is never dull. She tends to involve herself in all sorts

of scrapes and unsuccessful scams, carrying me with her into endless trouble.

However, she is a cheerful girl and has a blithe spirit in adversity. So

far, I must admit, we have not run into much, but in war-torn England you

can never tell.

About

the first person I had seen on boarding the Queen Elizabeth was my friend

Charlie. I should have known that was inevitable. She and I seem fated

to spend our service life in harness. We have already done 18 months together

as motor-transport drivers in Newfoundland. But I was glad to see her.

Life with Charlie is never dull. She tends to involve herself in all sorts

of scrapes and unsuccessful scams, carrying me with her into endless trouble.

However, she is a cheerful girl and has a blithe spirit in adversity. So

far, I must admit, we have not run into much, but in war-torn England you

can never tell.

I hope she gets back in time for this parade. Having been

stricken by hunger pangs, she has sneaked away to the kitchen door of the

officers’ mess to inveigle food from some overworked cook to sustain

her during the inspection. Only Charlie would have the nerve to do this

just before the advent of royalty.

Now I can see her weaving her way through the crowd clutching

a paper bag.

"What’s in the bag?" I ask.

"Say, the King must be staying to lunch, no spam today.

I got roast beef sandwiches in here all plastered with Gentleman's Relish,

whatever that may be."

"It’s like pickle, my father uses it all the time, he

even puts in on sardines." I have a sudden nostalgic flashback to our dining

room in Montreal and see dear old Dadsy with the pickle bottle at the ready

by his elbow.

Charlie digs into the paper bag and fishes out two hunks

of bread bulging with juicy meat. I eat in such a hurry everything gets

wedged somewhere round my tonsils.

"Didn’t you bring anything to drink?" I ask.

"For crying out loud, I told you to come with me. I had

some orange squash, could have had beer instead, but I was afraid I might

breathe on the brass."

At this moment I heard the sergeant major calling out

the markers. Charlie looks around wildly for somewhere to stow her empty

paper bag and finally wedges it behind the hangar door. At the call to

fall in we shuffle on to the tarmac and I lose sight of Charlie in the

general upheaval. After the usual fuss and flap we are sized into flights

and I end up in the front rank two down from the marker. I can hear a sergeant

bawling at someone and figure it must be Charlie being dumb. That girl

does not know her left from her right.

Now, in a parade, the front rank is not a good position

if you wish to remain invisible, which has always been my aim in service

life. You are much better off in the middle or rear rank.

Important people invariably talk to front-row persons

when reviewing a parade. However, it has been my experience that these

important people also tend towards certain types. I you look all gung-ho

and hearty you are sure to be singled out for a question. On the other

hand if you droop like some tired old horse, obviously wishing you had

never heard of the air force, let alone joined it, important people home

in instinctively, as it is clear you need backing up lest you collapse

on the ground entirely.

The best way to avoid all this unwanted attention is to

stare fixedly at the horizon looking slight idiotic. Important people steer

clear of idiots, though this is sometimes difficult as there are so many

about. I have practised this policy with great success since leaving Manning

pool and have yet to be asked a question on parade.

I cannot see much of what is going on as we are at the

rear directly behind a big flight of WAAF. On either side of the tarmac

four Lancasters have been drawn up, no doubt for authentic decoration.

Their great wings cast shadows at our feet.

Although my view of the royal party is nil I can tell

at once when they arrive. There is a sort of breathless hush and the NCOs

glance down the flights to make sure we are all behaving .

Now begins the raison d’etre for the King’s visit. He

is awarding medals to aircrew. One by one as their names are called these

recipients march up to have the awards pinned on their chest. Then comes

the tragic names, the posthumous awards. These me will never wear medals

they sleep forever in England or Europe, of cradled in the depths of the

sea. I wonder what Charlie is thinking. Her brother was killed at Dieppe.

The inspection begins. I hope it will be short as my legs

are getting tired. To pass the time I stare up at the Lancasters. How big

and deadly they look as they loom over the tarmac.

Suddenly our flight is called to attention. Out of the

corner of my eye I can see a group of people approaching, their leader

awesomely recognizable. Incredibly they bypass the marker and stop in front

of me.

It is an indescribable sensation being eyeball to eyeball

with the King of England. I am quite numb. Never again in this life will

I be such a centre of attention, or feel so inadequate. Four very senior

officers, air marshals, have their eyes on me, also a WAAF senior person

with scrambled egg on her cap whom I have never seen before and our own

women’s division commander, who sill boil me in oil if I do not do her

credit.

But they all pale into insignificance as I meet a pair

of very blue eyes. The King looks magnificent in the uniform of Marshal

of the Air Force. He asks me kindly where my home is and do I like England.

I remember to says "Your Majesty" to the first question and "Sir" to the

second. He passes on down the ranks and I fervently hope I have not

looked like the tired old horse. Won’t my mother be pleased! She will tell

all her friends, making it sound as though the King had invited me to Buck

House for tea.

Later in the mess hall Charlie asks me what the King said.

When I tell her, she remarks rudely: "Wonder why he’d bother talking to

you." I tell her it is because I have such an intelligent and beautiful

face, a rare combination. She laughs so hard she chokes on a Brussels sprout.

But much much later Charlie is not laughing at all. In

the early dawn I wake in our Nissen hut to see her sitting on the cot next

to mine, smoking. The only lights comes from the evil little stove that,

belching smoke and coke fumes, keeps us all warm through the night. I go

and sit beside her on the narrow bed, asking what is wrong.

"Ah." She says sadly, "the parade today has made me think

of Dicky. He was my twin, you know." Her only bother too, this boy killed

at Dieppe.

So we sit together in the gloom ruining our lungs with

cigarette smoke, grieving silently for the dead youth of our generation.

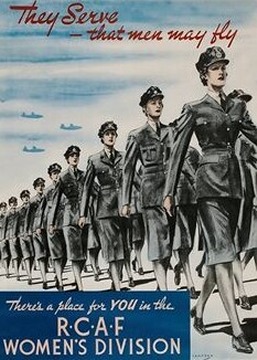

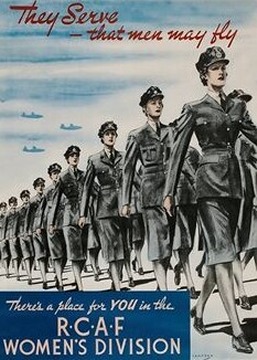

King George VI inspecting members of the Royal Canadian Air Force

Women's Division

139

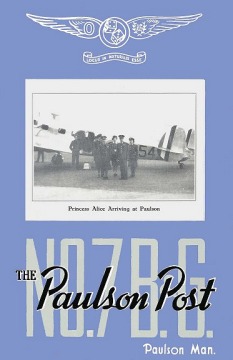

of 150: No. 7 AOS and No. 14 EFTS – Portage la Prairie, Manitoba

.

.

No. 7 Air Observers School - 1944 :: Class 81N (2) -

New Zealanders

No. 7 Air Observer School opened on April 28, 1941, across

a country road from No. 14 Elementary Flying Training School which opened

on October 28, 1940 in the Rural Municipality of Portage la Prairie, Manitoba.

No. 7 was open for 1,433 days while No. 14 was open at this location

for 613 days. While the two were co-located south of the City or Portage,

they shared a 15 bed hospital. The cost to build both schools was $450,000

($7,266,666 in 2017 dollars) by Claydon and Company.

The elementary school opened with eight large buildings

including an airman’s quarters, an officers’ mess and quarters, an Non-Commissioned

officers’ mess and quarters, a hangar, ground-instruction school, plus

a stores building and garage. When this school was transferred to Assiniboia,

Saskatchewan, the air navigation school took over these assets for its

own training needs.

The larger air navigation school opened with 12 large

buildings including a double-hangar, a single hangar, an individual mess

and quarters for officers and a combined mess and quarters for NCOs and

airmen, wireless building, direction finding equipment building, motor-transport

building, stores building workshop and headquarters building. No.

7 AOS was one of three Air Navigation School operated privately by Canadian

Pacific Airlines with the Royal Canadian Air Force providing the training.

Initially, Commonwealth Air Forces operated with Air Observers

trained in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan Air Observers Schools.

Streamlining of Bomber Command crews led to the deletion of the Air Observers

positions in favour of Navigators whose job descriptions were re-written

to better meet the needs of the air crews. Thus was born the Navigator

B (Bomber) who were deployed to large bombers with large crews (e.g.

Lancasters Halifaxes) and the Navigator W (Wireless) who were assigned

to smaller combat aircraft such as the Mosquito which flew with a pilot

and navigator.

In all cases the Observers or the Navigators would first

complete training at an Initial Training School and then were transferred

to the air observer school for more advanced training. This was followed

by Bombing & Gunnery School for Observers and Navigator B air crew

, or Wireless School for Navigator W air crew. The Observers and

Navigators would complete their training at an Air Navigation School.

The curriculum at No. 7 Air Observers School included

training in air navigation, air photography, reconnaissance, observation

and mapping.

The elementary school utilized the de Havilland Tiger

Moth aircraft for training while the air observer school used the Avro

Anson.

After World War II, the aerodrome was used by a number

of RCAF units until 1949 when it was closed. It was re-opened in the 1950s

as a training school for the RCAF and NATO (North American Treaty Organization)

air forces.

Today it is the site of the privately owned Southport

Aerospace Centre catering to commercial and industrial customers. A good

portion of the World War II buildings still remain at Southport along with

a new control tower and barracks, located away from the original buildings.

Southport is home to No. 3 Canadian Forces Flying Training School, associated

with 17 Wing based in Winnipeg, Manitoba. It provides Primary Flight Training

and Helicopter Training.

Here are some interesting statistics gleaned from a book

named "The Record" which was produced as a souvenir when No. 7 Air

Observer School closed in 1945.

No. 7 AOS – The Numbers

Period of Operation – three years, 11 months

Airmen Graduated – 5,176

Hours flown (1/3 night flying) – 201,536

Miles flown – 24,184,320

Average training flight hours – 3:15

Average training flight miles – 350

Fatal Crashes – five

Maximum number of aircraft on charge – 95

Buildings maintained – 45

Gasoline, gallons, aviation – 5,494,800

Gasoline, gallons, motor transport – 105,065

Oil, gallons, aviation – 161,382

Oil, gallons, motor transport - 2410

Electricity, kilowatts – 4,380,900

Water, gallons – 73,079,150

Meals served to Air Force personnel – 2,514,186

Civilian Employees – maximum, including messing staff

– 904

Operating budget, 1944 - $2,220,000

Savings on operations, 1941-1945, returned to Dominion

treasury - $644,306.89

140

of 150: A WWII Memory - Glen and Sam Merrifield - Part 14

During

the fall of 1943, we who had been overseas more than three years were offered

an opportunity to return to Canada. The reports we had from those arriving

from Canada told us they were still playing "soldier" pretty hard back

there so we declined. The thoughts of marching past the flag at attention,

saluting officers, attending parades, signing in and out at guardhouses,

having passwords and polishing boots and buttons, except for going on leave,

were activities we did not wish to resume after a long freedom from them.

During

the fall of 1943, we who had been overseas more than three years were offered

an opportunity to return to Canada. The reports we had from those arriving

from Canada told us they were still playing "soldier" pretty hard back

there so we declined. The thoughts of marching past the flag at attention,

saluting officers, attending parades, signing in and out at guardhouses,

having passwords and polishing boots and buttons, except for going on leave,

were activities we did not wish to resume after a long freedom from them.

Around this time Flight Engineers became common and many

of our fitters re-mustered to aircrew. One such was a chap named Bishop.

He was a Sergeant fitter, who when he applied, was given a FE (Flying Engineer)

wing brevet, put in John Fauquier's crew and sent on ops almost immediately,

John knowing his capabilities. The Problem arose when shortly thereafter

he was given an aircrew medical which he did not pass. His one mission

was a good one as I believe John was Deputy Master Bomber that night and

Bishop spent 45 minutes over Berlin on his first operational flight. He

had a fine time for a few weeks thereafter going around telling all and

sundry to "Get One in".

The Squadron Summary of Events for January 10, 1944 shows

under VISITS AND INSPECTIONS Their Majesties, The King and Queen, accompanied

by their retinue, the Deputy AOC in - Chief RCAF O'seas, A/V/M N.R. Anderson,

the AOC Pathfinder Force (8 Group), A/V/M/ D.C.T. Bennett, C.B.E. D.S.O.

visited this station for the primary purpose of meeting aircrew of 405

(RCAF) Squadron. In spite of INCLIMATE (sic) weather, the ceremony was

carried out successfully. This was probably a very busy period in their

Majesties lives and we forgive them for not stopping by our billet and

seeing us. I shall probably skip Buckingham Palace on my next trip to London.

Rumors abounded that prior to "D" day Hitler would strike

at Bomber Command Airbases and especially Pathfinders with parachuted troops.

As a precaution all hedges and concealment was removed from around the

drome and we were issued rifles and Sten guns which we carried at all times

during this period. Thank goodness it did not

happen because a half hours practice session on a Sten

gun does not really qualify one for defence against trained troops.

At Gransden we started a section softball league which

resulted in a squadron team being chosen. I saw some service on this team

which resulted in me writing a 1980 anecdote called "Fastball, Fortresses

and Food" here it is;

Being the only Canadian Squadron in Eight Group PFF which

was located between U.S. Sth Air Corp at Bedford and the U.S. 9th Corp

at Chelmsford we never missed a chance to play a game of fastball with

the American lads and then make pigs of ourselves on their creamed canned

peas and peaches and all sorts of goodies we never saw at any RAF drome

in over four years. Their B-17 Flying Fortresses we were shown with much

pride and we spoke many fine compliments to properly set the stage. We

noted that the bomb doors could not cope with more than a 1000 lb bomb.

Now our Lancasters were off limits to other than PFF types due to H2S etc…

However we could take them out and stand them under the nose and open the

bomb doors and watch their mouths drop open. They never really believed

that an RAF twin engine Mosquito with two of a crew aboard could carry

as large a bombload as their Fortresses with 13 men aboard. Our demonstration

showed them that our "Heavies" could with ease carry 3 to 4 times as much

as theirs. Took the sting out of the beating they usually gave us on the

ball diamond.

In early June 1944 we all awaited the news that the second

front had been opened. This day I was in Cambridge on day off and overheard

a pilot from another drome telling another he was scheduled for a 4 a.m.

takeoff, a very unusual hour in Bomber Command. On returning to camp I

was informed our time was the same and so I told the assembled poker players

that tomorrow was 'D' day. I was laughed at of course and when I went up

for breakfast next morning nobody was talking about it so I assumed I had

made a bad guess. On the shortcut bikepath to the drome from the mess,

I met the overnite drome crews coming the other way and they had been listening

to the radio and announced the invasion of the continent.

During our time at Gransden, Alex Sochowski, a Wolseley

(Saskatchewan) boy, joined the squadron. Alex, a Flying Officer, flew as

Navigator on Tomzaks crew in "M" for mother. The crew was lost but Alex

survived the war as a POW.

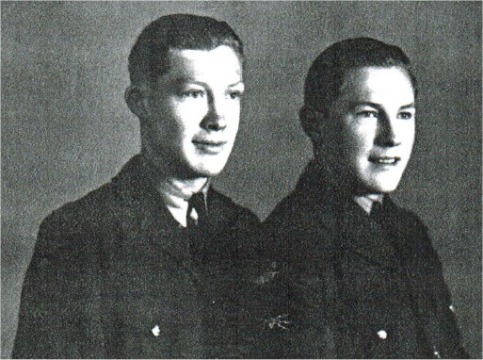

The Fleming brothers, Ralph and Les, from Summerberry,

a town eight miles from our home town Wolseley, joined the squadron at

Pocklington and served through to Gransden with us. One was a fitter and

one a rigger. Another Summerberry resident Don McQuaid, known as "Tex"

around the squadron, came to us as a Squadron Leader after service as a

pilot in Coastal Command and was soon promoted to Wing Commander as a Flight

Commander. Don won the DSO & DFC and had over 30 ops to his credit

when we returned to Canada in November 1944…

Fall 1944 brought War Bond time and we sent our ball team

to local villages to play a game for the locals to spur the Bond Rally.

We had our own for the first time too as the 1980 anecdote about "War Bonds"

relates:

During '44 at Gransden Lodge when the availability of

supplies were much improved someone felt that a show was needed to induce

the patriotic spirit and get the lads to buy udar Bonds. We were much excited

as we were told our Bombers would fly around in formation, something many

of us in our fourth year in Bomber Command had never

seen. Now the supply angle in '44 allowed our drome to

have a fighter stationed there for fighter affiliation exercises. What

a far cry from the summer of 1940. Our formation flying was grand but would

the Bonds bought at our drome pay for the petrol? Silly question... press

on... very grand. Now the finale... the Lancasters all down safely, the

Spitfire starts to beat up the drome to show some Fighter Command flying.

About the middle of the runway on his second pass he got too low... chips

flew from the end of his prop... he pulled up and got in safely. One advantage

of a wooden prop that splintered.

Maybe we broke even financially... hope so.

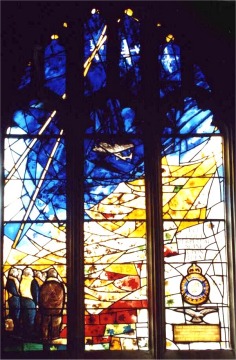

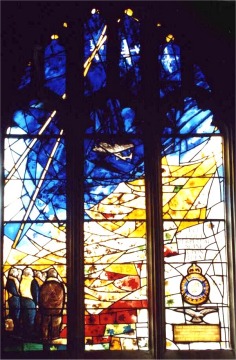

405 RCAF Squadron Memorial Window

St. Bartholomew's Church

Three light south facing window in St. Bartholomew’s in Great Gransden,

Huntingdonshire.

The 405 Royal Canadian (pathfinder) Squadron window was installed

in 1989.

‘Let light perpetual shine upon them’

This design is a memorial to the 900 men lost in bombing missions

and represented as falling maple leaves.

http://www.glenncarterglass.com/architectural/architectural_glass_barts_3.html

Click for full-size preview collage

.

. .

.

About

the first person I had seen on boarding the Queen Elizabeth was my friend

Charlie. I should have known that was inevitable. She and I seem fated

to spend our service life in harness. We have already done 18 months together

as motor-transport drivers in Newfoundland. But I was glad to see her.

Life with Charlie is never dull. She tends to involve herself in all sorts

of scrapes and unsuccessful scams, carrying me with her into endless trouble.

However, she is a cheerful girl and has a blithe spirit in adversity. So

far, I must admit, we have not run into much, but in war-torn England you

can never tell.

About

the first person I had seen on boarding the Queen Elizabeth was my friend

Charlie. I should have known that was inevitable. She and I seem fated

to spend our service life in harness. We have already done 18 months together

as motor-transport drivers in Newfoundland. But I was glad to see her.

Life with Charlie is never dull. She tends to involve herself in all sorts

of scrapes and unsuccessful scams, carrying me with her into endless trouble.

However, she is a cheerful girl and has a blithe spirit in adversity. So

far, I must admit, we have not run into much, but in war-torn England you

can never tell.

.

.

During

the fall of 1943, we who had been overseas more than three years were offered

an opportunity to return to Canada. The reports we had from those arriving

from Canada told us they were still playing "soldier" pretty hard back

there so we declined. The thoughts of marching past the flag at attention,

saluting officers, attending parades, signing in and out at guardhouses,

having passwords and polishing boots and buttons, except for going on leave,

were activities we did not wish to resume after a long freedom from them.

During

the fall of 1943, we who had been overseas more than three years were offered

an opportunity to return to Canada. The reports we had from those arriving

from Canada told us they were still playing "soldier" pretty hard back

there so we declined. The thoughts of marching past the flag at attention,

saluting officers, attending parades, signing in and out at guardhouses,

having passwords and polishing boots and buttons, except for going on leave,

were activities we did not wish to resume after a long freedom from them.