141

of 150: Vernon Watson Oral History Video

The following Oral History Video was recorded in Gladstone

Manitoba in 1996 as part of that town’s Cable Community Access Channel

celebrating Canada Remembers. The Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum

has added this video to our Oral History archives.

The following Oral History Video was recorded in Gladstone

Manitoba in 1996 as part of that town’s Cable Community Access Channel

celebrating Canada Remembers. The Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum

has added this video to our Oral History archives.

Vernon Watson enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force

in 1941. He graduated from the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan as

a Bomb Aimer with a Flying Officer commission.

He joined the 138 Special Duties Squadron flying supplies

to the underground organizations in Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium and

France. He flew 41 missions.

Vernon Watson’s Oral History Video can be seen

on YouTube at:

https://youtu.be/7mFZ1DpAtkY

After the war, Vernon bcame a member of the Gladstone Legion

and the Wartime Pilot’s and Observers Association.

Vernon Watson died in March 2006 in Gladstone, Manitoba.

142

of 150: War Brides - Sea of Love

Sea of Love

Our Canada Magazine - November 2010

By the end of the Second World War, thousands of British

and European women had sailed to Canada as the wives or "war brides" of

Canadian servicemen. Here are just a few of their memorable tales.

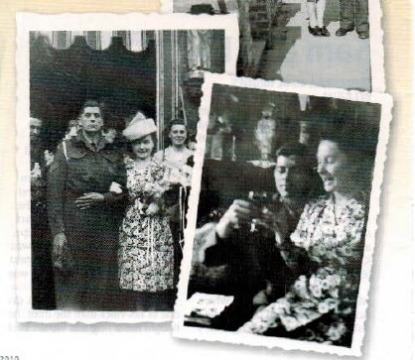

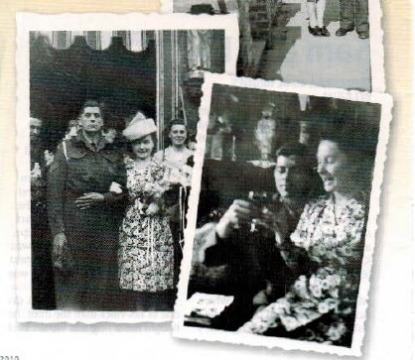

Sam and I

SEPTEMBER I944, BRUGES, BELGIUM

Cecile and Sam honeymoon in Brussels ~ Wedding at City Hall, Bruges

~ Enjoying a good luck drink at the wedding

Since the landing of the Allied forces in Normandy weeks

earlier, we had been waiting to be liberated On September 12, a few neighbours

and I were assembled in the street

ready to go back to the cellar where we'd been sleeping

when we heard footsteps clattering along the pavement. Our hearts began

to pound as two soldiers In khaki uniforms approached. Were they Brits?

No. Ken and Sam were Canadian artillery troops. Sam asked me a lot of questions.

Where had I learned English? Where did I live? What kind

of work did I do? I have friends in England, I answered; I live in No.

7 on this street and l'm a teacher.

My neighbour mentioned that he was having trouble receiving

news from his sister in Ontario, so Sam offered to contact her through

his folks back home. Sam would pick up a letter from my neighbour to send

the following morning.

Over the next few days, Sam and I went to the city centre

and walked the streets along the canals. On September 16, Sam asked me

to be his girl for keeps, believe it or not! I accepted. He was a handsome,

quiet man. The next day, Sam announced his battery was moving out.

We began a courtship by mail. On one or his visits from

the front, he bought me a ring and we decided Sam to get married as soon

as the war ended. Warnings from family and friends about soldiers followed,

but I was sold.

In the meantime, I returned to work, but not as a teacher.

I found a good job with British Civil Affairs and later British Civil Censorship.

MAY 6, I945

Peace

.

JUNE 30, 1945

Our wedding! at city hall in Bruges, the wedding was

followed by a small gathering at home. Mother had prepared a small dinner,

and there was still a shortage of food. Sam left for Canada and I had to

work.

MAY I946

The day had finally arrived for me to go to Canada. I

travelled from Oostende to Folkestone, England, where I boarded the ship,

Aquitania.

After six days at sea, with many other war brides on board, we arrived

in Halifax, a truly unforgettable sight.

But there were no husbands to meet us. We were asked to

register and then brought to the train station. I had never travelled in

a train with sleeping facilities before. Looking through the window there

was nothing but water, rocks and forest. Arriving at Toronto’s Central

Station, names were called and I was sent into a long hallway, and there

was Sam in civies - a moment I'll remember forever.

Toronto was a city out of a dreamland; tall buildings.

streetcars and lots of people. We drove to Hamilton, where we were going

to live. Sam's sister threw a smull party in her home in honour of our

reunion.

Sam had rented the upstairs apartmem of a nice little

house. There on the table stood a coffee pot, a toaster and a frying pan

ready for breakfast! The next day, it was on to the grocery store.

I was stunned to see all the goods there.

One day we went to visit Sam's parents in Manitoba. That

was a real eye-opener for me. Theirs was a lone farmhouse in the middle

of nowhere close to the Saskatchewan Border, with no electricity, no running

water, an outhouse and lots of land and cattle.

We returned home to Hamilton, but later moved to Winnipeg.

Moving to friendly Manitoba began the most important period of my life

in Canada. I was accepted as a teacher and encouraged to continue my education

at the University of Manitoba, where eventually I was offered a teaching

position. l stayed at the university until I retired in 1981. Sam enjoyed

working in Winnipeg, too. We made a lot of friends there.

Upon retirement, we moved to Ottawa to join join our son

and his family. We soon got to know many wonderful people in the apartment

building where we lived. Sadly, Sam took ill and passed away in 2002. He

was laid to rest in Beechwood, the military cemetery in Ottawa, where I

will join him when my time comes.

~ Cecile Ungrin-Gevaert Ottawa

A Long Journey Home

I943, FOLKESTONE, ENGLAND

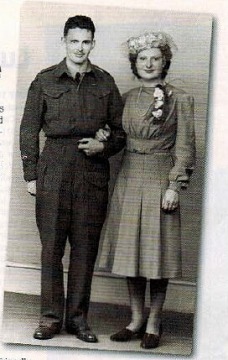

July 7, I945: John and Gwyneth were married in England

and reunited in Canada in I947.

I

joined the women's Auxiliary Air Force during the Second World War in England,

happy to leave an unexciting office job. After an intensive training session,

I was posted to a Fighter Command base on the south coast. I was their

first female electrician.

I

joined the women's Auxiliary Air Force during the Second World War in England,

happy to leave an unexciting office job. After an intensive training session,

I was posted to a Fighter Command base on the south coast. I was their

first female electrician.

I first met my future husband, John, a Canadian soldier,

in I943 at a services dance in nearby Folkestone. Our meetings always

ended suddenly as the "shell warning" sounded and the enemy guns on the

French coast opened fire across the English Channel. D-Day brought further

separation.

We were married in July I945 at a little stone church

in the Kent countryside. John returned to Canada in January 1946 and I

followed a year later with our baby son.

We were passengers on the last troop ships crossing of

the Aquitania. It was also transporting the final contingent of

war brides to Canada. Conditions on board were more crowded than usual.

I shared one section somewhere in the bowels of the ship with about 40

other women and children. We were separated from a busy and drafty gangway

by a canvas sheet.

Sloshing in bilge water, we washed the baby nappies in

seawater. The terry cloth squares dried like a bed of nails. No wonder

the babies never stopped crying! When a winter storm hit, washrooms became

a shambles, baby bottles smashed and frustrated infants lost their usual

form of nourishment from their seasick nursing mothers.

When the stonn abated, an epidemic of gastroenteritis

broke out among the younger children. No treatment was possible, other

than to keep them on a glucose solution.

A thick fog swept across the Atlantic and swallowed up

the ship. The Aquatania finally limped into Halifax harbour way

behind schedule. Ambulances took the sick children to the navy hospital

HMCS Stadacona. My three-month-old son was among the admitted.

The Salvation Army came to the resrue of the stranded

mothers. They gave us food, shelter and hot cups of tea. I will never,

ever forget their kindness. A week later, we were able to continue our

long train journeys across Canada. My destination was the small town of

Cochrane, in northern Ontario. The friendly train porters insisted that

it was in Alberta, while others claimed that it was at the North Pole!

Unknown to me at the time, John had heen waiting in Nonh

Bay, Ont. for more than a week with no sign of the war bride train's arrival.

Finally, at some ungodiy hour, he poked his head through the Pullman curtalns

of my sleeper car. His face was half buried in a huge fur hat with

earmuffs. Who is this strange Russian? was my first reaction. This thought

was quickly followed by, My God, what have I done? He certainly looked

very different from the Canadian soldier in uniform l remembered.

Homesickness sent me back to England in 1950. This time,

the At!antic remained calm, which was just as well, as I had three

little boys in tow! My mother was not well and as she stood waving goodbye

to us at the Liverpool dockside, I sensed that I would never see her again

- and I never did.

Our arrival back in Canada coincided with a train strike

right across the country. It took four different flights in small planes

to reach an airfield in Iroquois Falls near Timmins, Ont.. It was summer

and my in-laws had a cottage nearby. John, along with some family

members, other cottagers and even a few dogs turned out to welcome us home.

It was wonderful to finally be safely back in Canada.

ln 1952, we were blessed with a daughter. Forty three

years of marriage to a good and faithful husband came to an end with John's

death in 1992. I now live with my daughter in the Muskoka area. The years

have gone by, but the memories will always remain.

~ Gwyneth Shirley, Huntsville, Ont.

Lucky in Love

MAY I943, ENGLAND

What a lucky day it was when I met my Canadian. It resulted

in my coming to Canada and enjoying 62 years of a wonderful life, so far.

Joe and I met aboard the HMS Westcliff in May 1943.

He was a Canadian naval commando and I a British Wren. He took me ashore

on a movie date and I was fascinated to hear all about Canada. We planned

our wedding in August 1944 and we married in December of that year.

My first officer had received ten wedding dresses in various

sizes for the use of Wrens not wishing to to be wed in uniform -- from

a women's group in Texas. All I had to do was pay for the dry cleaning

and send a photo to the club of me wearing the dress. Excitement was not

the word for my feelings. I chose a gorgeous satin, seed pearl dress with

a six-foot train, the likes of which you never saw in wartime Britain!

The next exciting event was my notification that I would

be sailing from Southampton on August 6, 1949, on the Queen Mary

along with our nine-month-old son, James. On

board, I remember thinking that the bread was cake. I

arrived at Pier 21 In Halifax, wooden-soled shoes on my feet and strange

money in my hands.

Park Avenue in Montreal was my destination. Meeting my

new family was fabulous. They gave me lots of bridal showers, helped me

to learn French and taught me how to cross the road without getting run

over!

We settled in the Laurentians. My first winter was scary;

the snow was so deep I didn't think I'd ever see green again. But I did

and still do.

My mother, sister and brother eventually joined us. Joe

and I had six children and raising them in the relaxed atmosphere of the

Laurentians was a delight.

I travelled back to England in 1961, again on the Queen

Mary. That's when I knew that my adopted country was for me and felt,

once again, how lucky I was to have fallen in love with a Canadian.

We moved to Calgary and in 1976, I joined the War Brides

Club. It was lovely hearing all those different accents once again. I met

Bev Tosh, a Calgary artist who was very interested in our group, as her

mom was a war bride from New Zealand. She felt that out stories should

be told, so she painted more than 50 of us, all on our wedding days, on

rough wood canvases, which were then turned into a whole exhibition.

The Canadian government helped out and the show has now

been seen by thousands of people around the country. I'm very honoured

to have my picture in this exhibition.

I love Canada and feel truly blessed. Joe passed away

in March 1989, but my children are Canadians and have contributed to Canada's

wonderful melange.

~ June Stewart-Burgoyne, Calgary

A total of 48,000 war brides and their 22,000 children

entered Canada via Pier 21 in Halifax during and after the Second World

War. An immigratlon hub since the 1920s, Pier 21 was put under Ihe control

of Canada's military in September I939 and became a major war-time link

between Britain and Canada.

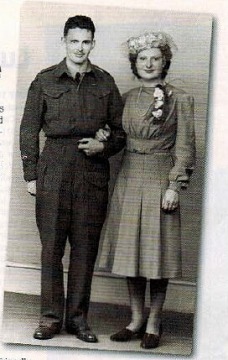

143

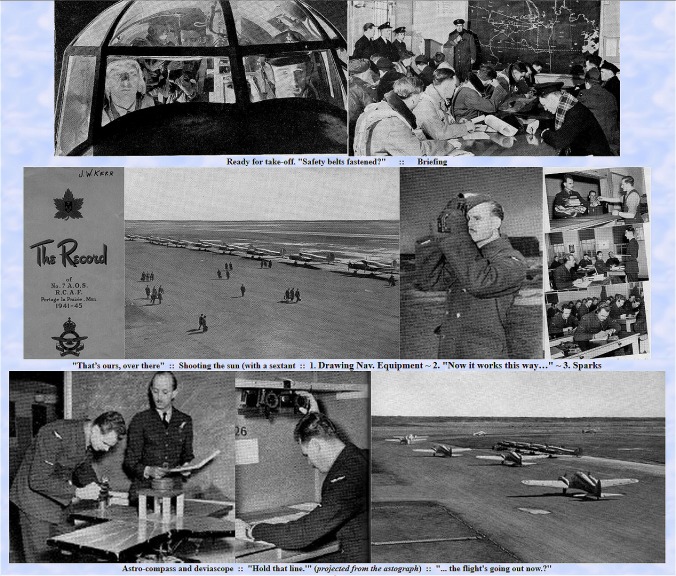

of 150: Farewell - No. 7 Air Observer School, Portage Manitoba

The following two articles are from

"The Record," a farewell booklet handed out at No. 7 Air Observation School

in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba at the end of the war. The school, which

had graduated many Observers and Navigators, became redundant with the

cessation of the air war and was closed in 1945. The first article

is a detailed synopsis of training offered at No. 7 AOS and how it morphed

to meet the changing needs of the Commonwealth Air Forces as the war progressed.

The second article gives the reader the "ins and outs" of the first week

at an Air Observer School for a new student. Both are interesting reading

with the first perhaps, a little lengthy and dry… you be the judge of that.

THE TRAINING STORY

The priceless value of these scientifically trained young

men, graduates of the A.O.S., is something which cannot be overstressed.

Even the best Pilot in the world, the most deadly-eyed Gunners, the great

Bomber and its cargo of sudden-death-to-the-enemy lose all value, as may

the lives of the crew, should the young man in the navigator's seat, the

Air Observer, be improperly trained, slipshod or inaccurate in guiding

the ship to its target and bringing it home again.

That is often overlooked by the uninitiated. "The best

Bomber Pilot in the RC.A.F. is just as good as his Navigator.'' (Leslie

Roberts, "Canada's War in the Air.") At first there were many of

"the uninitiated," not least among recruits dreaming of earning their pilot's

wings and tossing a single-seater fighter from cloud to cloud. But with

the Battle of Britain won, the R.A.F. taking the offensive over Europe,

and big and ever bigger aircraft coming off production lines for Bomber

and Coastal commands, the spotlight moved away from the fighter pilot to

focus on that new unit, "our crew"; on teamwork; and on that: Bomber

of the air war, the self-forgetting, each-for-all, air crew spirit.

As the importance of the Observer, and then of his specialized

successors, the Navigator and Bombaimer, grew in operational experience

and in public notice, so too, the training changed. Those first Observer

students to enter A.O.S. back in the experimental days of the summer of

1940 faced the task of learning what later became two men's jobs; and of

learning them in a 22-week course, where each; the combined training of

their successive teams eventually totalled 40 weeks.

In the words of a 1941 account: "At the A.O.S." the map,

chart, compass, bombsight and camera became the student's tools. He learned

how to read maps and charts, how to read instruments and correct compasses,

how to know what to look for, and how to report it to his crew or his station.

He must also learn Morse well enough to receive or send eight words a minute

on the buzzer and six on the lamp; learn photography to be able to i:ecord

bomb destruction, troop placements, railway networks. "Still another important

duty of the Air Observer is to drop the bombs-and that's not just a matter

of dumping them out willy-nilly. He's got to be able to plant a stick astride

a battleship from more than a mile high and to do so through reckoning

against his own speed, the wind speed and the speed of the ship. It is

an exact and important science, and packs a thrill all of its own."

To master these duties, the Observer spent three months

in A.O.S. studying basic navigation-that is fundamental dead reckoning

(his central task for the duration), map and chart projection and

principles of map reading, compasses and instruments-with aircraft recognition,

reconnaissance, visual signalling, photography, and armament; and did 60

hours flying.

Then he moved on to a Bombing and Gunnery School for six

weeks, to learn in theory and practice how to handle the Vickers and the

Browning machine guns, both on the ground and in the air. He practised

range estimation and marksmanship with these weapons. He studied the theory

of bombing and the workings of a bomb sight and dropped two score (40)

bombs on the Station range. The range was a mile wide to allow for his

initial errors; but there were times when the spotters in the range hut

found it uncomfortably narrow.

For most Observer courses, it was graduation from Bombing

and Gunnery School that brought the coveted wing with the big "0." A sergeant's

stripes replaced the LAC's propeller. And a sergeant's pay was not unwelcome.

The last four weeks of his training in Canada, the observer

took at Air Navigation School, at Rivers, Man. or Pennfield Ridge, N.B.

There he learned astro as an aid to navigation-to find his way by the bearing

of the stars and planets at night and of the sun by day, using the sextant

and the blank plotting sheet. There, too, he practised advanced navigation

and advanced bombing.

Long-range aerial operations and mass bombing attacks

were still in the future, and astro-nav. was not rated as highly then as

later. In those early days, a wonderful new instrument had just come out,

which helped the Observer to establish his position by the stars more quickly.

But specimens were rare. '’The instrument, was highly secret at first"

in the words of one of the first observer to graduate from the Air Training

Plan "and we were taken one by one into a tiny cubicle and shown -- the

astrograph."

A 20-mile error at a turning point was acceptable at first

in training, where later one or two miles became the tolerance. An 8-minute

error by dead reckoning against Estimated Time of Arrival would get by.

Four years later the tolerance in training was three minutes; while on

operations, bomber captains briefed for German targets made bets on the

skill of their navigators that would be settled by a difference of seconds

from the correct time of arrival at the bombing point.

"By contrast with today, we just fumbled along in those

days," in the words of the early graduate quoted. But the "fumbling" was

good enough that as many of those first Observer graduates finished their

embarkation leave, each was assigned as sole Navigator on the trans-Atlantic

crossing of a North-American-built bomber being ferried to Britain.

From that not inadequate level of performance, the standard of observer

training was improved steadily throughout the duration of the Air Training

Plan.

With the coming of longer-range aircraft and the approach

to "1,000 bomber" raids, the navigational responsibilities of the Observer

grew steadily heavier. Ever greater accuracy was required, to find small

targets in spite of growing difficulties. The navigator had to cope with

long distance from base, night, the enemy blackout, fighter opposition,

flak, and the puzzle of keeping track of course while the aircraft was

weaving madly to avoid being coned by searchlights or boxed by enemy aircraft

or detectors. To help the navigator somewhat, constant research was carried

on to develop mechanical aids. But these aids themselves called for more

specialized training.

In the summer of 1942, therefore, the duties of the Observer

were divided between two new air crew trades. those of Air Navigator and

Air Bomber, or Bombaimer. The navigator was to be responsible only for

navigation, becoming "the brains" of the navigation team-a human

calculating machine rarely able to leave his desk in the aircraft from

take-off until return to base. In training for this, he was to take a 16-week

course at an A.O.S., combining the former 12-week A.O.S. and 4-week A.N.S.

courses and omitting Bombing and Gunnery school. The new course included

60 hours of day flying and 36 hours of night flight. On graduation, it

was the wings parade on his A.O.S. that he received the now "N" wing and

his sergeant's hooks.

The Bombaimer undertook a double duty. He became the specialist

responsible for placing his aircraft's load squarely on target from whatever

height might be necessary, by exact target finding and bomb aiming. And

he was to be assistant to the Navigator acting as "the eyes" of the navigation

team, by supplying positional data obtained through map reading and through

use of the sextant, drift instruments, astro-compass, etc. For this he

was to train eight weeks at a Bombing and Gunnery school, then pass for

six weeks to an A.O.S. for· applied bombing, map reading and navigational

training, with emphasis on night bombing, completing some 60 hours in the

air by day and night.

The new stress on extremely accurate navigation and on

specialized training for it was accompanied by a standardizing and tightening

of navigational methods. Both the Navigator's and the Bombaimer's courses

eventually were lengthened to 20 weeks, to permit still more thorough training.

Dead reckoning remained the basic skill, but astro, radio and radar aids

became more prominent and ever greater exactness was required.

The early student Observers had heard of the astro-compass;

their Navigator successors became familiar with it in training. Sextants

were improved, synthetic dead reckoning trainers and celestial navigation

trainers were introduced. And to begin early the fostering of administrative

responsibility, air crew leadership training was added to the course. To

free time for the new activities, the old photography and reconnaissance

subjects were washed out of the Navigator's syllabus.

With the new subjects and the old, went always the routine

of physical training, drill, parades and inspections and of maintaining

acceptable dress and deportment. Even with changed studies and the longer

course, the student's day remained crowded.

Through four years at No.7, and to the end despite cheering

news out of Europe, the classroom windows of the Ground School building

blazed into the night. Behind those lighted windows, students were at work

after hours, so keen to do their best that for them the use of the quiet

rooms in the evening was truly described by the card upon each classroom

door-"Late Study Privilege."

THE STUDENT'S EXPERIENCE

The foregoing is the training story as the graduate or

instructor looks back upon it, over the five years' operations of the Commonwealth

Air Training Plan. But to the student at the time, training looked

somewhat different:

Arriving at No. 7 Air Observer School, usually on a Saturday

about midday, he climbed out of the bus or truck that had brought him over

five miles of dusty gravel road from the railway station, reported in,

was taken in charge by two Training Wing Warrant Officer, paraded to the

Stores to draw his bedding, then was marched to quarters to be shown his

share of a double bunk, and made up his bed. The rest of the Saturday and

most of the Sunday, he had to himself.

On Monday morning, he was introduced to the instructor

assigned to his course. And filled out his personal index card for the

Station records. Then he paraded with the others to the Navigation stores

in the G.I.S. building, to draw his training equipment. After that, the

course paraded to the Recreation hall, where they were welcomed and

given wise advice by the Manager, the Chief Supervisory Officer, the Padre,

Medical Officer, and the Special Services Officer.

A tour of the Station, under the guidance of the instructors,

began the afternoon. The student had been in the Air Force for several

months before he arrived at A.O.S. and had not yet flown. So, to see dozens

of Anson aircraft lining the tarmac was quite a thrill. He also took an

eyeful of the coveralled girls handling the gas trucks so smartly,

as they refuelled the aircraft parked on the line.

The care and use of a parachute and how to bail out of

an aircraft were the next topics of his first Monday. Crowded into the

parachute room with his course mates, the student listened to a talk

and demonstration on this life preserver that probably he never would need,

but which he would only need and lack once. The talk and demonstration

were given by a woman at No. 7, a fact that invariably amused the new students

at first. But amusement changed to respect as they took in the pithy explanation

and found themselves quickly outfitted, each with a parachute harness that

would accompany him on every flight until he left the Station months later.

The taking of a class photo with the new course grouped

in front of an aircraft, ended a day that left the new Student well content

to roll into his bunk that evening.

On the Tuesday, his fourth day on the Station, the student

began Ground School classes. Not until a week later were he and his course

taken for their first flight, in daytime, to become familiar with the aircraft

that would be their flying practice rooms, to get the feel of flight-and

to be able to rejoice that, after long weeks in Manning Pool and Initial

Training School, at last they were approaching "the real thing."

After the four introductory days, the new student found

himself settling quickly into a routine of Ground School classes, flights,

Physical Training, drill, parades, inspections, games, recreation, and

last, but very far from least, meals and snacks. So crowded were his days

that he was absorbed in routine almost too quickly to be aware of the fact.

For most of the students were so keen, always straining

forward to "the real thing," that the mass of training detail was taken

in stride in a way that won the warm respect of the instructors. In his

training hours, the student progressed from the elements of navigation

and the theory of dead reckoning, celestial navigation and the rest to

rehearsal in the synthetic dead reckoning trainers, the map reading room,

the sextant trainer, and "the silo" or the celestial navigation trainer.

From these, he passed to airborne practice on day flights,

first, then on night flights, with always greater responsibility. All the

time he was becoming ever more conscious of his instruments, particularly

of his navigation wrist watch. When he arrived on the Station, a five minute

margin seemed punctual enough, and he thought in local time. When he graduated,

he thought automatically to the nearest second and in the Greenwich time

of navigators the world over, from which he did mental translation

to keep local "dates."

Working hard for most of his training hours, seven days

a week, the student was ready for his "48"-hour leave when it came around

every tenth day. A visit to Winnipeg usually made the time pass too quickly.

Then it was back to the Station, to press on towards graduation day and

the dreamed-of, waiting "O" "N" or "B" wing that would be the proud symbol

of his aircrew trade.

PHOTO SCRAPBOOK

Click for full page size

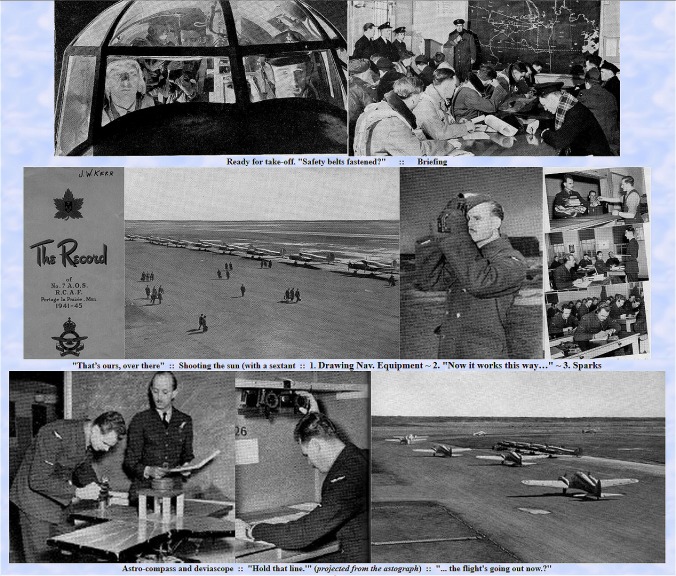

144

of 150: CATPM Motor Transport - The Marmon-Herrington 6x6 Crash Tender

The Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum Marmon-Herrington 6x6

Crash Tender

In addition to the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum’s

collection of 20+ aircraft and thousands of small artifacts and archival

materials, the museum has a collection of 28 motor transport vehicles.

With one exception, they are correct to the period of the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan and a good portion of them had careers with the Royal

Canadian Air Force during the war. Included in the mix are three automobiles

(Dodge, Chevrolet and Chrysler), one jeep, a Ford three ton fuel

tender truck, two SnoGo snowblowers, an International K8 Fire Truck, International

K Series two ton truck, International K Series Panel Truck, International

K Series panel truck, Dodge two ton truck, Dodge one ton fire truck, Chevrolet

two ton stake truck, International and Ford tractors and a D2 caterpillar.

A most impressive member of the CATPM motor fleet is a

1944 Ford 6X6 (all-wheel-drive) Marmon Herrington Crash Truck. The story

of the Marmon Herrington Company is fascinating as well.

The Marmon-Herrington Company of Indianapolis, Indiana

got its start as the Nordyke and Marmon Machine Company, founded in 1851

to produce flour milling equipment. It morphed into the Marmon Car Company

in the early 1900s to produce high-end automobiles for 30 years. It was

the Marmon Wasp which won the first Indianapolis 500 race in 1911 in almost

seven hours and with an average speed of 74 miles per hour.

When the worldwide economic depression of the 1930s caused

massive closures and bankrupting of businesses throughout the world and

severe unemployment and economic hardships for most people, demand for

the prestigious Marmon cars disappeared. To evade a fate similar to thousands

of other companies, the Marmon Company merged with an ex-military

engineer named Arthur Herrington, in 1931, to produce rugged and dependable

four-wheel-drive vehicles for the military and limited civilian use. The

first vehicles off the production line were designed for towing military

weaponry. In most cases, the Ford Motor Company provided basic, heavy trucks

which were fitted with Marmon-Herrington mutli-axle drivetrains.

Many years before the American Willys company developed

the well known four-wheel drive Jeep for military use, the Ford Motor Company

and Marmon-Herrington company were collaborating to make four-wheel and

six-wheel-drive trucks. The collaboration came about when Ford realized

the folly in re-inventing drive train technology already available from

Marmon-Herrington. Ford had been unsuccessful in the production of these

drivetrains. These trucks were a big hit with military customers

all over the world.

The first Ford/Marmon-Herrington vehicle produced for

the Canadian military during World War II, was a 4x4 truck customized to

meet the needs of the army. The air force also acquired fuel tenders for

use at its many aerodromes across the country. This truck and the

three-ton, six-wheel-drive crash tender were not customized to Canada’s

needs, but were already in production for a number of armed forces across

the world.

The RCAF acquired the 6x6 in great numbers to serve at

its aerodromes across Canada. They were very capable of responding to fires

and crashes on RCAF property as well in fields and other off-road locations

adjacent to, or near the airfields where conventional vehicles could not

travel. These trucks were equipped with fire-fighting equipment supplied

by the Walter Kiddie or American La France companies. A typical configuration

included a water tank and pump, foam developing equipment (mechanical and

chemical) and carbon dioxide cylinders.

The CATPM Marmon-Herrington crash tender was built in

1944 and was stationed with the RCAF during the war. It is currently roadworthy

and has most of its fire-fighting equipment mounted on the truck although

it is non-operable.

After the war, other Marmon-Herrington ventures included

the development of military tank drive units, airport fire trucks and trolley

busses from 1946 to 1959. The company continues to produce transfer cases

and axles for trucks and specialty vehicles. It is now one of the many

successful corporations owned by the Berkshire-Hathaway company.

Sources:

www.mapleleafup.nl/marmonherrington/truck.html

www.mapleleafup.nl/marmonherrington/truck_nei.html

www.offroadxtreme.com/features/history/vintage-monday-marmon-herrington-trucks-jeeps-grandfather/

www.marmon-herrington.com/company

I

joined the women's Auxiliary Air Force during the Second World War in England,

happy to leave an unexciting office job. After an intensive training session,

I was posted to a Fighter Command base on the south coast. I was their

first female electrician.

I

joined the women's Auxiliary Air Force during the Second World War in England,

happy to leave an unexciting office job. After an intensive training session,

I was posted to a Fighter Command base on the south coast. I was their

first female electrician.

.

.