051 of

150

A World War II Memory - Sam & Glen Merrifield

Our first installment of this wartime memory was published

in our Canada 150 Vignette No. 48. It followed brothers Stan and Glen Merrifield

from tennage life on the farm in Shoal Lake Manitoba to their completion

of British Commonwealth Air Training Plan training. At that time, we had

no intention of going into their experiences overseas with the Royal Canadian

Air Force. A second reading of the rest of the story brought us to the

conclusion that it was loaded with wonderful insights into all facets of

life as airmen in a foreign country during World War II. We decided to

serialize the story (25000 words) into 14 installments to be published

in our Canada 150 Vignette serices. This is the second installments and

it explores Stan and Glen's voyage to England to join the No. 3 Bomber

Group the Marham Aerodrome in Norfolk England.

We

loafed around until the 27th of September when we were taken with our worldly

belongings to docks and put on the Duchess of Athol, a CPR boat; there

was one more air force man who was an Air Commodore. All the other passengers

were civilians and included the actors, actresses and film crews returning

to Britain after filming scenes of "49th Parallel".

We

loafed around until the 27th of September when we were taken with our worldly

belongings to docks and put on the Duchess of Athol, a CPR boat; there

was one more air force man who was an Air Commodore. All the other passengers

were civilians and included the actors, actresses and film crews returning

to Britain after filming scenes of "49th Parallel".

We were put into cabins which held four people and in

addition to Glen and myself, our cabin had Dick Lewington and Teddy True

both of whom had been in our class and both of whom had lived in England.

Dick until he came to Canada and Teddy as a child while his father was

with the Canadian Diplomatic Service. One evening we saw some of the film

shot in Canada, mostly at Banff, but while they tried to fill in the story

it is not a highlight in my memory.

The currency used on the boat was the British Sterling

and the first thing we had to do was to change our Canadian money into

Pounds. As I recall the exchange rate was four dollars and eighty cents

for each Pound. Glen was given a five Pound note in part payment for his

money. At that time such notes were printed on one side only of a tissue

like material which had to be folded over to bring it down to the size

of an ordinary note. He treated it with a certain amount of scepticism

and was not long in spending a part of it to get change in one pound notes

which looked and felt more like the money we were used to handling.

I have no recollection of what the eating arrangements

were but I believe that we ate in the same dining facilities that the other

tourist class civilians used. In any event we fared much better than we

would have had we been on a troopship. We were not in a convoy and as a

result, we were given duties doing submarine lookout, which involved standing

at the front of the deck just below the bridge keeping a lookout for submarine

periscopes. The shifts were for two hours and came around every two days,

with two men on each shift. The only thing spotted was in our last day

out when the Air Commodore who was checking up on us, spotted what turned

out to be a deflated barrage balloon floating past some distance from the

boat.

The trip took eight days and after landing in Liverpool

on October 5 we were taken to Padgate, a depot near Warrington, Lancashire.

We were there until October 11, 1940 and were introduced to the British

way of doing things which was to make your bed in a specified manner and

to keep the floor area under and around it highly polished. In the early

evenings we would go into Warrington to the cinema or pubs on the bus,

however, when the air raid sounded, which was most evenings, the busses

stopped where they were until the all-clear sounded. This meant that we

were obliged to walk back from town to be in by the prescribed time.

Glen, myself and Jack Duller were all sent to Marham Norfolk

and it was a long tedious day making the trip by train with two train changes

before we arrived in Kings Lynn, Norfolk about nine o'clock in the evening.

From there we went to the Airdrome at Marham by bus which was returning

after having taken people to the base city for the evening.

We arrived in time to be given beds in the barracks room

occupied by signals people being all air force except one who was an army

signalman called Stiffy Hardwick who maintained the equipment at the transmitter

station. While some of the others were newly in the air force, several

of.the others in the signal section were permanent force men with three

or four of them having gone through Cranwell, the RAF signal school, as

boy apprentices who joined up at the age of fifteen or sixteen and had

therefore had several years training. They were known as Trenchard's Brats.

Trenchard being the first head of the RAF after it was changed from RFC.

Many had been through France and Norway and were the backbone of the fine

technical standard of the RAF at that period. As boys, they spent part

of each day learning airforce trades and the rest of the day with general

school activities befitting boys their age. These general school activities

were shortened to Gen, an abbreviation that became the word used for any

information on any subject.

Marham was a permanent air force base and had red brick

buildings. At one end of the square were the headquarters offices with

the signals section at the rear and all was surrounded by a high brick

wall heavily banked on the outside with earth. The canteen movie and other

recreational facilities for the enlisted men were at the other end of the

square. There were three barracks blocks along each side of the square.

The facilities for the officers were back off the square but I do not recall

in which direction.

The airdrome was in Three Group and contained two Bomber

Squadrons flying Wellington aircraft powered by Pegasus Engines. Since

our work was in the signals cabin, there was no need for us to get out

among the aircraft and we never even walked over to the hangars during

the eight months we were there. Glen said he did and was asked his business

as security was much tighter in the early part of the war. As well as wireless

operators, the signal cabin was staffed by teleprinter operators who also

resided in the same barracks as we did. During the day shift, they were

busier than we because they were constantly sending and receiving messages

whereas the wireless operators had only to tune in on the air ministry

frequency every hour on the hour and only rarely was there a message to

take down, always in code.

On nights when there were operations there was a full

complement of operators listening on five or six frequencies. The aircraft

maintained radio silence until they had dropped their bombs after which

they sent an 'X' signal code saying so. They again called once they had

crossed the enemy coast and nothing more unless they were in trouble. Once

they were back in England and close to the landing field they switched

to the command set and spoke to the control tower. On nights when there

was no ops on there was only a wireless operator and a teleprinter operator

on duty along with a watch Corporal. We would take turns staying awake

for two hours and we could operate the teleprinters well enough to acknowledge

receipt of a message and the teleprinter operators could read enough Morse

code to know if there was or was not a message. If there was a message

to come they would awaken the operator to take it. When not awake, we slept

on the coconut matting on the floor using our ever present Gas Masks for

a pillow.

Our Signals Officer was a Flight Lieutenant by the name

of George Reece and the English chaps referred to him as the Wolfe of the

signals cabin. He was a taciturn individual and I think the only time I

had a conversation with him was when we were leaving the station at which

time he wished us good luck. Our presence at the station was a cause for

some concern because we three Canadians were leading aircraftsmen while

the English chaps who were better trained than we, were only AC2' s or

AC1 's. Our pay was also a great deal more than theirs, however, we had

assigned some of our pay home to be saved for us and the net result was

that on paydays we received about the same amount of cash as the others

did.

There was a General Duties kid in our barracks, an AC2,

whose daily pay was only sixpence which at the rate of exchange was only

twelve cents compared to our two dollars. This lad always needed some extra

pocket money and was more than glad to polish the area under our bed for

sixpence, which was done once a week the evening before the inspection

of the barracks.

I don't think we had a day off as such but because we

were on shift work, a change in shifts could result in a 32 hour respite

when there was ample time to run into Kings Lynn on the camp bus which

left daily about noon and returned about eleven in the evening. This gave

us time to do some sightseeing, have our tea and see an early showing of

a movie before going back to camp. One of the teleprinter operators that

I frequently was on shift with was Jimmy Corbold who came from Bury, St.

Edmunds where his mother ran a pub and on two or three occasions,I went

home with him by the usual method of hitch hiking.

Jack Duller brought a silver grey shirt overseas with

him which he wore on dress occasions. He was frequently accosted by the

authorities who he convinced that it was permissible Canadian issue. One

of our Corporals purchased a car and one night four of us went off to a

dance at Downham Market. During the war, all automobiles had shields on

their headlights to restrict the amount of light given and thereby reducing

the field of vision to a few feet. Coming home the driver mistook a white

line on the edge of a tank barrier at the side of the road and on a curve,

for the line on the road, with the result that we crashed into the barrier

and wrecked the car. Except for a few bruises and some cuts to the Corporal's

face, we came off very well. We were taken to the home of a local ARP Warden

who attended the cuts and then drove us home. During the dance while I

was dancing with the daughter of the master of ceremonies, we won a spot

dance and my prize was a pair of gold plated cuff links which had been

purchased by the donor for her son who was an aircrew member of the RAF

and had been killed before she was able to give them to him.

Every three months we were entitled to a seven day leave

and at least one forty eight hour pass. If one took them together and began

leave just after a shift change, it added up to ten days. Every other leave

entitled us to a railway warrant to any place in the British Isles, which

gave us free transportation. When the time came around for our first leave,

we thought that Glen, Jack Duller and I could all go together but somehow

that was rejected and we had to go separately.

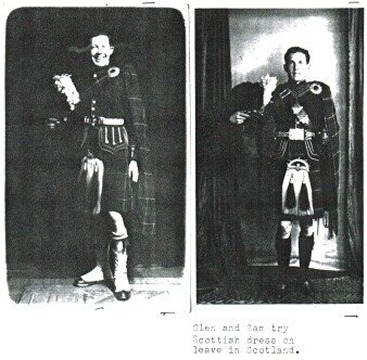

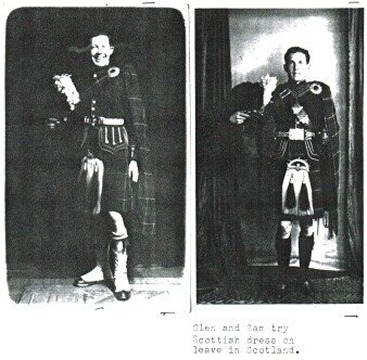

Both Glen and I went to Glasgow which was not being bombed

as frequently nor as heavily as London. The Fitzroy Hotel on the end of

Sauchihall street had been converted into an overseas service mans facility

and I was able to get a room for a very nominal sum during my stay.

Sometime in April, Jack Duller contacted pneumonia and

was sent to a Military Hospital in Ely. At or about the same time, Glen

was either on leave or on a course and learned that the powers that be

intended forming all Canadian Squadrons and he was able to get the

name of someone to contact to request a posting to such a squadron. The

result was that on the 12th of May 1941 we bid good-bye to Marham Norfolk

and went to Driffield, Yorkshire. Jack was still in hospital and while

he was also posted he did not arrive until 405 Squadron had moved to Pocklington

some weeks later.

Glen here. . . . the name I was given was F/Lt Hammond

c/o Air Ministry, London. After our successful posting I passed this information

on to all Canadian lads I met who would want the same treatment One later

told me he got holy hell for doing an end run around his CO and the establishment

and writing Air Ministry. All I can say is I am one LAC who did it and

got results and no brickbats.

052 of

150:

Canada Yanks in the RCAF

Canada’s Yanks: Air Force, Part 16

July 1, 2006 by Hugh A. Halliday

In April 2017, the Commonwealth Air Training Museum in

Brandon Manitoba received a request for assistance from the office of Tim

Ryan, representative for Ohio in the United States Congress. He is the

co-sponsor of a bill to recognize the legacies of 12000 Americans who joined

the fight for democracy in WWII prior to the United States’ entry into

the war. The bill is known as: “American Patriots of WWII through Service

with the Canadian and British Armed Forces Gold Medal Act of 2017.”

Asked and given, the CATP Museum forwarded a letter

in support of this bill to the Congressman. In addition to recognition

for their service to the Commonwealth armed forces, the honorees will be

eligible for a medal to be struck if the bill passes. This motivated us

to see if there was a story for the Canada 150 Vignette project from this

act of remembrance. We found a good one written by our good friend Hugh

Halliday who wrote this article for the Legion Magazine in July 2006 telling

the story of those Americans who came north of the border to join the Royal

Canadian Air Force. We present this interesting and informative story below.

We offer special thanks to Hugh Halliday.

Canada

declared war on Germany on Sept. 10, 1939. The Royal Canadian Air Force

(RCAF) had been expanding in anticipation of this; now it fairly exploded,

doubling in size within four months. Meanwhile, on Dec. 17, Australia,

Britain, Canada and New Zealand signed an agreement creating the British

Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). Canada was about to become a vast

air force training centre, with schools from the Atlantic to the Pacific

and students from around the globe. Many of those trained would be American

citizens.

Canada

declared war on Germany on Sept. 10, 1939. The Royal Canadian Air Force

(RCAF) had been expanding in anticipation of this; now it fairly exploded,

doubling in size within four months. Meanwhile, on Dec. 17, Australia,

Britain, Canada and New Zealand signed an agreement creating the British

Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). Canada was about to become a vast

air force training centre, with schools from the Atlantic to the Pacific

and students from around the globe. Many of those trained would be American

citizens.

Initially, the RCAF did not seek out Americans; there

were more than enough Canadians volunteering. Moreover, with the United

States still neutral, there would be diplomatic problems if American citizens

were enlisted, much less courted. However, U.S. nationals began to arrive,

motivated by everything from love of adventure to political convictions.

As more BCATP schools opened, the RCAF found itself short

of trained pilots. It began looking for experienced Americans to perform

non-combat duties. This led to the formation of the semi-secret Clayton

Knight Committee, the brainchild of aviation artist Clayton Knight and

the RCAF’s Director of Recruiting, Air Marshal Billy Bishop VC.

The committee opened its first office in New York’s Waldorf

Astoria Hotel in the spring of 1940; other bureaus were established in

Spokane, Wash., San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Kansas City, Cleveland,

Atlanta, Memphis and San Antonio. Various devices were used to create the

fiction that the Clayton Knight Committee was a private advisory unit.

In practice it was recruiting Americans on American soil in violation of

the Neutrality Act. Moreover, although its goal was to direct trained pilots

to Canada, increasingly the committee gave information to untrained Americans

who wanted to join the RCAF. These raw recruits constituted 85 per cent

of the Americans ultimately enrolled in the RCAF.

One problem was the Oath of Allegiance to King George

VI. An American taking the oath could be deemed to have forfeited his U.S.

citizenship. In June 1940, Canada waived its Oath of Allegiance for foreign

nationals, who henceforth were asked only to take an Oath of Obedience.

In other words, they were to follow the rules of military discipline for

the duration of their RCAF service.

Training centres began to resonate with American accents;

some courses were comprised of 50 per cent of American students. Many more

claimed to be Texans than was actually the case; girls who would not have

been attracted to somebody from Rhode Island, might find a man from Texas

more interesting.

As of Dec. 8, 1941, approximately 6,129 Americans were

members of the RCAF. Just over half–3,883–were still undergoing training,

but 667 were on operations overseas while others were engaged in flying

duties in Canada itself, instructing, flying anti-submarine patrols, etc.

With America’s entry into the war, RCAF recruiting there ceased and American

volunteers began heading for USAAF (United States Army Air Force)

offices instead. Americans residing in Canada were still being enrolled,

however. Ultimately, the RCAF calculated that more than 8,860 U.S. nationals

joined that force.

Within a month of Pearl Harbor, talks were underway for

the transfer of Americans from the RCAF to U.S. flying services. In May

and June 1942, a board of Canadian and American officers travelled across

Canada by special train, affecting the release of 1,759 Americans from

the RCAF and enrolling them simultaneously in American forces. Transfers

continued throughout the war. The RCAF calculated that 3,797 Americans

switched back to their own national forces. That left 5,263 Americans who

elected to stay with the RCAF throughout their service careers.

Many of the Americans had very distinguished battle records,

but there is no question as to who gained the greatest fame. Pilot Officer

John Gillespie Magee, Jr., who was born in China of missionary parents,

wrote the moving poem High Flight while training with the RCAF. He was

killed Dec. 11, 1941, when his Spitfire collided with an Oxford aircraft

in England. The original manuscript of High Flight is in the Library of

Congress in Washington, D.C.

An estimated 234 American members were decorated. The

earliest of RCAF Americans to be honoured was Sergeant George E. Mitchell

of Diamond Springs, Calif. He graduated as an air gunner in March 1941,

and was promptly sent overseas where he joined 7 Sqdn., flying Stirlings.

In June 1941, while serving as rear gunner, he shot down a Me.110 as it

attacked his aircraft. Mitchell was awarded a Distinguished Flying Medal

in November 1941; unhappily, he was killed in action on April 6, 1942.

Some of the RCAF’s most highly decorated aircrew were

American nationals. These included Squadron Leader David C. Fairbanks of

Ithaca, N.Y., who earned three Distinguished Flying Crosses while flying

Spitfires and Tempests, shooting down 16 enemy aircraft in the process.

Following the war, he threw in his lot with Canada, joined the Toronto

branch of de Havilland and became an executive with that company.

Also much decorated was Russell E. Curtis from Albion,

Pa. He enlisted at Niagara Falls, Ont., in October 1940, earned his wings

the following July, and wound up flying Wellington bombers with 104 Sqdn.

in North Africa. In December 1942, he was awarded the DFM in recognition

of great skill and knowledge. The citation noted that on two occasions

he brought aircraft safely back to base in spite of flak damage in one

instance and engine failure coupled with bad weather in another.

Following his tour with 104 Sqdn., Curtis was commissioned

and sent back to England. In July 1944, now a flight lieutenant, he began

a second tour, this time with 428 Sqdn., flying Lancasters. In August 1944,

he and his crew were detailed to attack Dortmund, Germany. During the bombing

run the aircraft came under heavy anti-aircraft fire and was hit. Curtis

sustained a compound skull fracture. Despite the severity of his injury,

he bravely remained at the controls and pressed home his attack. Not until

the task was accomplished did he ask for assistance. He afterwards collapsed

and was placed in the rest position. Other members of the crew took over

the task of flying the Lancaster home; eventually it was landed by the

bomb aimer. Six members of the crew were decorated for their roles in the

incident; Curtis received a Distinguished Service Order.

Nor was Curtis unique among Canada’s Yanks. Flight Lieutenant

John H. Stickell of Gilson, Ill., and Flt. Lt. William J. Senger of St.

John, N.D., both earned the DSO and DFC. Stickell was also mentioned in

dispatches. Both were bomber pilots flying Stirlings. Stickell began with

214 Sqdn. in May 1942 but was posted to 7 Sqdn. in August that year. Senger

arrived at 7 Sqdn. in October 1942; his first operational sortie was flown

as Stickell’s co-pilot. Eventually, both transferred to the United States

Army Air Force, Stickell in March 1943, Senger in October 1943.

Sergeant Charles E. McDonald of Shreveport, La., was one

of a kind. He enlisted in the RCAF in September 1940, earned his wings

in April 1941, and was duly posted overseas, flying Spitfires with 403

Sqdn. On Aug. 21 he was shot down over France and taken prisoner. Yet his

war was only beginning. On Aug. 11, 1942, with three other prisoners, McDonald

escaped from Stalag Luft III. Aided by the Polish underground they assumed

new identities that enabled them to cross Germany and occupied France,

pass over the Pyrenees Mountains to Spain, and eventually reach Gibraltar.

From there, they returned to England. During his long journey he witnessed

Allied bombing raids on Berlin.

McDonald was awarded the Military Medal, a decoration

normally associated with army personnel but awarded infrequently to airmen

who escaped captivity. He was the only member of the RCAF ever to receive

this honour. Late in the war he transferred to the USAAF, saw action in

the Pacific, and went on to fly Sabres in Korea. Unhappily, McDonald was

killed in a flying accident in November 1953.

Not all awards were for “gallantry in the face of the

enemy.” On Jan. 28, 1943, Sgt. Clinton L. Pudney of Buffalo, N.Y., was

air gunner in a Halifax bomber engaged in a training flight in Yorkshire,

England. The aircraft hit high ground, crashed and burst into flames. Three

crewmen were killed; all others, except Pudney, were too badly injured

to extricate themselves. Pudney had sustained lacerations and lost blood,

but he returned several times to the burning wreck until he had rescued

four comrades. He then struggled two miles over rough moors to summon help.

Pudney was awarded a George Medal. Tragically, he died after his aircraft

was hit by lightning on June 16, 1943.

Roughly 800 Americans were killed while serving with the

RCAF, including 148 in Canada itself. Most of these–117–involved training

accidents, but 31 were killed on operations such as transport, ferry work

and anti-submarine patrols. The first of Canada’s Yanks to die–on March

31, 1940–was Leading Aircraftman Edward E. Hood of New Bloomfield, Pa.,

killed in an automobile accident while on strength of RCAF Station Trenton,

Ont. The second fatality (and first flying casualty) was LAC Chester M.

Wood of New York City. He was under instruction at Trenton when his Fleet

Finch went into a spin and crashed on June 16, 1940. Flt. Lt. James L.

Mitchell of Venice, Calif., was the first to die on operations; his Hudson

disappeared on a trans-Atlantic delivery flight on Jan. 9, 1941. At least

two American members of the RCAF died in flying accidents in Britain before

July 30, 1941, when Sgt. George R. Menish of Salina, Kansas, was killed

in action flying a Blenheim light bomber with 139 Sqdn., the first of many

combat casualties sustained by Americans in the RCAF.

Of the Americans killed in Canada, whether in training

or on operations, most bodies were returned to their hometowns for burial.

A few, however, were interred in cemeteries close to the places where they

died, chiefly because of the presence of family or close friends in Canada.

Those killed overseas and whose bodies were recovered were buried in the

countries where they fell–Britain, France, Holland, Belgium, Germany–to

name the most frequent nations. The men with no known graves are commemorated

on the various memorials dedicated to those who vanished.

Most of the American fatalities were in their early 20s,

but some were “old men” by aircrew standards. Flying Officer David F. Langmack

of Lebanon, Ore., was 39 when he died in a Lysander crash at Suffield,

Alta., Sept. 22, 1941. Flt. Lt. Charles Lesesne of Sumter, S.C., was 34

when he was killed in action with 425 Sqdn. on March 31, 1945.

Although Canadian authorities strove to keep RCAF personnel

together in Canadian formations, approximately 50 per cent of RCAF strength

overseas was scattered through RAF units, and the American members of the

RCAF were similarly dispersed. Most saw action in the North African and

European theatres, but some ended up on secondary fronts. Two Americans

serving in the RCAF were killed in Burma; Flt. Lt. Lloyd D. Thomas of Detroit

earned a DFC flying Hurricanes with 5 Sqdn. before being killed by Japanese

ground fire on April 18, 1944. Pilot Officer O.A. Keech of Alexandria,

N.Y., was killed March 4, 1944, while dive-bombing in a Vultee Vengence

aircraft of 84 Sqdn. Others died in even more remote places and in unusual

ways. Warrant Officer Charles R. Dixon of Mount Vernon, N.Y., was serving

in a meteorological flight in the Sudan. On March 10, 1943, while taxiing

an obsolete Gladiator biplane, he blundered into a fuel dump and touched

off the fire that killed him.

Among those with unusual stories was John Harvey Curry

of Dallas. He enlisted in the RCAF in August 1940, trained as a pilot,

and wound up in North Africa with 601 Sqdn. In March 1943, as a flight

lieutenant, he was awarded the DFC for having destroyed seven enemy aircraft;

the citation described him as “a source of inspiration to his fellow pilots.”

However, his greatest exploit was still to come.

Curry was promoted to squadron leader and given command

of 80 Sqdn. On March 2, 1944, while strafing enemy vehicles in Italy, he

was shot down by ground fire. He force-landed in snow-covered mountains,

but was unhurt. With the help of friendly Italians, he avoided capture

and linked out with other Allied evaders. Curry and one soldier decided

to strike south through rough terrain to reach Allied lines. They began

their trek on March 12, suffering from hunger and cold along the route,

and contacted Indian Army troops about noon on the 18th. For this feat

of endurance and courage, Curry was made an Officer, Order of the British

Empire.

Not all the Americans were aircrew nor were all the awards

for flying duties. Flight Sergeant George F. Sullivan of Boston enlisted

in Montreal in November 1940 as a mechanic. Late in 1941 he joined 409

Sqdn., an RCAF night-fighter unit in Britain. Sullivan remained with the

unit throughout the war. In June 1945, he was awarded the British Empire

Medal for his work in keeping the unit active by maintaining a minimum

of six serviceable Mosquito aircraft even during the most intensive operations

and under the most adverse conditions.

There is a scene in the movie Captains of the Clouds

when Billy Bishop is presenting pilot’s wings to a 1941 RCAF graduating

class. One of the men is identified as Groves. As Bishop pins on the wings

a short conversation ensues:

Bishop: “And where are you from, son?”

Groves: “Texas, sir.”

Bishop: “One of our most loyal provinces.”

Groves: “We think so, sir.”

Bishop: “Well, I think so, too. And we thank you

for coming up here and helping us.”

The scene is a poignant reminder of a time when thousands

of Americans joined a foreign air force, determined to fight Hitler without

waiting for the U.S. to become directly involve https://legionmagazine.com/en/2006/07/canadas-yanks/d

https://legionmagazine.com/en/2006/07/canadas-yanks/

053 of

150: Boundary Bay, British Columbia

Number 4 Training Command of the Royal Canadian Air Forces

had a number of training units located in various locations in British

Columbia including Vancouver, Boundary Bay, Comox and Abbotsford, all on

the mainland, and Patricia Bay near Victoria on Vancouver Island across

the Georgia Strait from mainland BC.

RCAF Station Boundary Bay is located 40 km. south of Vancouver.

It

was the location of a number of training and operational units and was

open between April 1 1944 and October 21 1945 for 578 days. The first RCAF

unit to locate there was No. 18 Elementary Flying Training School which

was open from March 10 1941 to May 25 1942 for a total of 410 days. This

school was originally located in Vancouver (RCAF Station Sea Island) as

No. 8 EFTS before moving to Boundary Bay. De Havilland Tiger Moth

aircraft were used to train students. The school was sponsored by the Aero

Club of BC and operated, with civilian instructors, as the Vancouver Air

Training Co. Ltd. As a result of the Japanese attack on Pearl Island, No.

18 EFTS personnel and equipment were transferred to No. 33 Royal Air Force

Station Caron Saskatchewan effective May 25 1942 to avoid the RCAF’s perception

of a possible Japanese attack of Canada. In Caron, civilian staff took

over instruction from RCAF personnel.

With this move, room became available to provide fighter

protection to Vancouver. Three RCAF operational fighter squadrons were

posted to Boundary Bay. No. 133 Squadron operated with Hawker Hurricane

aircraft and Numbers 14 and 132 Squadrons operated with Curtiss Kittyhawks

Training continued at Boundary Bay with the opening of

No. 5 Operational Training Unit on April 1 1944. The Operational

Training Unit was the last installment of training for air crew who spent

eight to 14 weeks learning to fly operational aircraft such as the Hawker

Hurricane, Fairey Swordfish or larger multi-engine aircraft. Instructors

were generally posted to the OTU after completing one or more operational

tours.

Consolidated B-24L Liberator --India Air Force

At No. 5 OTU aircrew were trained to fly the Consolidated

B-24 Liberator, an aircraft held in high regard by the Royal Air Force

for operations in Asia and the Pacific Ocean. Nearby ocean and mountains

provided a good simulation for what aircrews could expect to experience

in the war with the Japanese Air Force. No. 5 OTU also provided training

in the North American B-25 Mitchell aircraft as a good step toward flying

the more powerful and complicated Liberator. Bristol Bolingbrokes saw duty

towing targets for gunnery practice, the Curtiss Kittyhawk provided fighter

affiliation exercises and the Noorduyn Norseman was used as a utility aircraft.

Mitchell -- Canada Air and Space Museum

When it was decided that Liberator aircrews required more

air gunners, a satellite to No. 5 OTU was established in Abbotsford BC.

Training would start in Boundary Bay and crews would graduate after completing

the supplemental training in Abbotsford.

No. 5 OTU wrapped up operations at Boundary Bay on October

31 1945. Boundary Bay operated as a demobilisation centre for the RCAF

until the base was closed in 1946. After World War II, Boundary provided

a home for the Royal Canadian Corps of Signal operating radio equipment

and gathering signals intelligence. In 1968, Boundary Bay’s name was changed

to Canadian Forces Station Ladner, in compliance with new protocols called

for with unification of Canada’s military forces. Transport Canada opened

Boundary Bay Airport to ease air traffic needs at Vancouver International

Airport.

Wikipedia - Canadian Forces Station Ladner - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canadian_Forces_Station_Ladner

Photo credit

By Mike Freer - Touchdown-aviation - Gallery page http://www.airliners.net/photo/India

-- Air/Consolidated-B-24L-Liberator/1139882/LPhoto http://cdn-www.airliners.net/aviation-photos/photos/2/8/8/1139882.jpg,

GFDL 1.2,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27016282

054 of

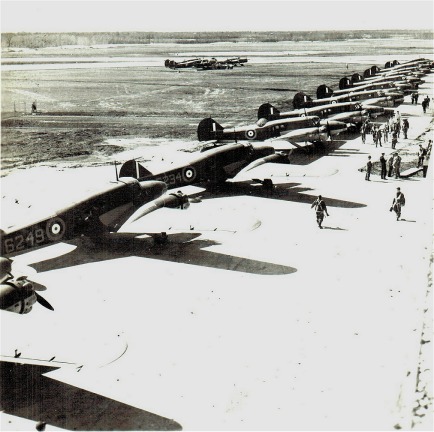

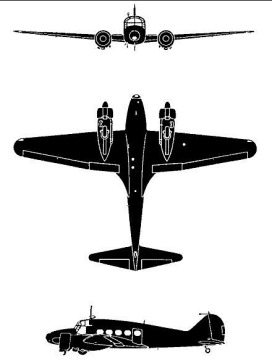

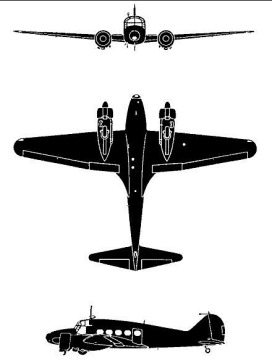

150: Aircraft of the Plan - The Avro Anson

By

far the aircraft adopted in greatest numbers by the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan was the Avro Anson. 8,138 were produced by Avro in Great

Britain and another 2,882 were produced under license by the Federal Aircraft

Ltd in Canada. As for total numbers built, it was second only to the Vickers

Wellington in the Royal Air Force.

By

far the aircraft adopted in greatest numbers by the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan was the Avro Anson. 8,138 were produced by Avro in Great

Britain and another 2,882 were produced under license by the Federal Aircraft

Ltd in Canada. As for total numbers built, it was second only to the Vickers

Wellington in the Royal Air Force.

The Avro Anson’s namesake was Admiral George Anson who

had a distinguished naval career with the Royal Navy in the first half

of the 18th century. He was a wartime commander in the numerous conflicts

of that time and as a captain who lead his crew on a voyage to circumnavigate

the world.

The first Anson of the initial order of 174 flew in 1935.

The last Anson in service to the Royal Air Force was a trainer and communications

aircraft which was retired in 1968. In Britain, this aircraft was

produced for the RAF, Fleet Air Arm and RCAF until 1952. The Avro Anson,

was a marvelous warplane in the 1930s but was deemed obsolete in this role

by the time World War II started in 1939, however it assumed a useful role

as a training aircraft and on coastal patrol during the war.

The Avro Anson is a twin engine single wing aircraft noted

for its working versatility. Production of the Anson was based on the Avro

652 airliner. The Anson’s initial purpose was as a maritime reconnaissance

aircraft in support to Fleet Air Arm’s larger and most costly flying boats.

The Anson was capable of carrying heavy loads for a long range. Early

models had wooden wings made of spruce and plywood, a welded steel tube

fuselage frame and were mostly clad in fabric. Its nose was moulded magnesium

kept to a minimum size so as to not impede forward visibility.

In a first for the RAF, the Anson had a retractable undercarriage

which was initially mechanical and hand operated requiring 144 turns of

a crank to raise or lower the landing gear. With the gear tucked into the

fuselage, the Anson was capable of an extra 30 miles per hour. The first

Ansons were powered by two Armstrong-Siddley Cheetah IX radial engines.

These Ansons were crewed by a pilot, navigator/bomb-aimer

and wireless air gunner. In 1940, requirements increased the crew to four

members. The bomb-aimer was located laying on his stomach in the forward

section of the nose with access to a bombsight, driftsight, other instruments

and a landing light. The pilot sat behind the bomb-aimer with modern instruments

and controls making the aircraft instrument flight rules (IFR) capable.

Behind and to the right (starboard) was room for an additional passenger.

The navigator was located behind this jump seat with a chair and table

complete with instruments including a compass, Bigsworth chart boards,

and wind and speed calculators. The wireless operator sat behind the wings

with a table and radio. This crew member had access to a winch witch could

be used to extend and retract an aerial behind the aircraft.

The pilot had control of a single .303 calibre Vickers

machine gun pointed ahead of the aircraft. The WAG had access to an Armstrong

–Whitworth manual gun turret with a single Lewis machine gun. The Anson

could carry 300 pounds of bombs on its wings.

Anson trainers included dual controls allowing for a pilot

trainee and no gun turret with the exception of those used for gunnery

training. They were equipped with a Bristol hydraulic gun turret similar

to that in the Bristol Blenheim

Ansons with maritime responsibilities were equipped with

an internal inflatable dinghy and automatic distress signals.

At the beginning of World War II, the RAF had 824 Ansons

in active service with 10 Coastal Command Squadrons and as trainers with

16 Bomber Command Squadrons in No. 6 Operational Training Group.

Lockheed Hudsons eventually replaced the coastal patrol Ansons. Ansons

provided training for pilots, navigators, wireless operators, bomb aimers

and air gunners.

The Royal Australian Air Force flew 1028 Ansons, mostly

Mark 1s. The Royal New Zealand Air Force flew 23 Anson navigation trainers.

The Anson flew in the Royal Canadian Air Force until 1952

as a trainer and for the RCAF Eastern Air Command in maritime patrol with

two 250 pound bombs. The RCAF utilized Mark II Ansons with Jacobs engines

and hydraulic landing gear and the Mark V for navigator training equipped

with Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior engines and wooden fuselages. One

Mark V! was built in Canada for gunnery training with two Wasp Junior engines.

A total of 23 variants of the Avro Anson were produced in Great Britain

and Canada.

We

loafed around until the 27th of September when we were taken with our worldly

belongings to docks and put on the Duchess of Athol, a CPR boat; there

was one more air force man who was an Air Commodore. All the other passengers

were civilians and included the actors, actresses and film crews returning

to Britain after filming scenes of "49th Parallel".

We

loafed around until the 27th of September when we were taken with our worldly

belongings to docks and put on the Duchess of Athol, a CPR boat; there

was one more air force man who was an Air Commodore. All the other passengers

were civilians and included the actors, actresses and film crews returning

to Britain after filming scenes of "49th Parallel".

Canada

declared war on Germany on Sept. 10, 1939. The Royal Canadian Air Force

(RCAF) had been expanding in anticipation of this; now it fairly exploded,

doubling in size within four months. Meanwhile, on Dec. 17, Australia,

Britain, Canada and New Zealand signed an agreement creating the British

Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). Canada was about to become a vast

air force training centre, with schools from the Atlantic to the Pacific

and students from around the globe. Many of those trained would be American

citizens.

Canada

declared war on Germany on Sept. 10, 1939. The Royal Canadian Air Force

(RCAF) had been expanding in anticipation of this; now it fairly exploded,

doubling in size within four months. Meanwhile, on Dec. 17, Australia,

Britain, Canada and New Zealand signed an agreement creating the British

Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). Canada was about to become a vast

air force training centre, with schools from the Atlantic to the Pacific

and students from around the globe. Many of those trained would be American

citizens.

By

far the aircraft adopted in greatest numbers by the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan was the Avro Anson. 8,138 were produced by Avro in Great

Britain and another 2,882 were produced under license by the Federal Aircraft

Ltd in Canada. As for total numbers built, it was second only to the Vickers

Wellington in the Royal Air Force.

By

far the aircraft adopted in greatest numbers by the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan was the Avro Anson. 8,138 were produced by Avro in Great

Britain and another 2,882 were produced under license by the Federal Aircraft

Ltd in Canada. As for total numbers built, it was second only to the Vickers

Wellington in the Royal Air Force.

.

.