089 of

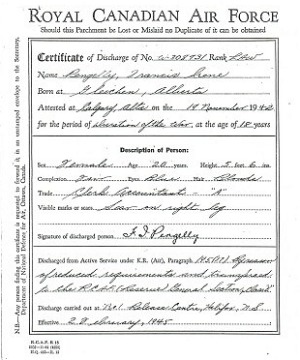

150: A WWII Memory -- Fran Pengelly WD

Reflections on my life as a W.D. in the R.C.A.F.

by Frances (McDowell) Pengelly

I

was 15 years old when World War II broke out. I was going to high school

in Delburne, Alberta a small town in central Alberta. I was the eldest

child in the family living on a farm just outside the village with my parents,

2 sisters and one brother.

I

was 15 years old when World War II broke out. I was going to high school

in Delburne, Alberta a small town in central Alberta. I was the eldest

child in the family living on a farm just outside the village with my parents,

2 sisters and one brother.

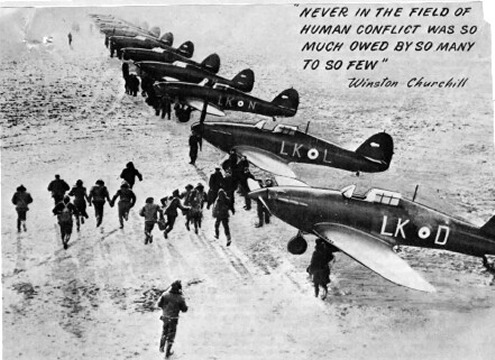

One of the things we as a family did was to turn on Winston

Churchill's broadcast each day to hear about the progress of the war. Anyone

whoever listened to this broadcast could never forget it, Sir Winston had

a very compelling voice and you just couldn't turn the program off. This

of course was on radio as there was no television at that time.

I was pretty young and as soon as Canada entered the war

some of the young men in our area enlisted, this was a much talked about

event as we personally either knew these young men or knew someone who

did know them. It was a very exciting time for us young people. I'm sure

very few of these young men ever thought about the consequences of war

it was just the exciting thing to do. As time went on and the war grew

to have tragic overtures I'm sure people thought more about it but in the

beginning it was just something to do. It wasn't long until some of our

high school classmates were enlisting. Some were very disappointed if they

were rejected, some accepted d this but others felt very differently. We

had one young man commit suicide as he felt so strongly about being rejected,

this was a boy I could remember all through my years at our school. I can

remember when the first boys from our area were sent overseas and also

when the first casualties were reported back to our district.

I was quite upset when my boyfriend David Pengelly enlisted

in the Air Force but he was 19 years of age and excited to join. Dave had

been gone six months or so and I got a job in the local Bank of Montreal

as a clerk keeping track of the ledgers and doing small jobs. I was a good

math student and really loved the work. I moved from my parents’ home to

a small apartment of my own in the Village.

I'm sure my bosses weren't very happy with me but I didn't

ask permission before I applied to join the Air Force. Propaganda definitely

played a part on my enlisting. In November the recruiting officers were

back in town and as of November 19, 1942 I was on leave from the R.C.A.F.(W.D.)

until December 14, 1942 when I was officially given the number W3*****

with the rank of A.W. 2 (air woman second class). I reported to Ottawa

where I was outfitted with clothing and took my basic training. That was

my first Christmas away from home but I was so busy I didn't mind.

We learned to march while here, the biggest problems were

sore feet from not being accustomed to those heavy shoes so blisters were

the order of the day. I had no trouble marching as I was always a good

walker. We girls took 27 inch strides but we had a terrible time when we

would be on parade with the men, they took a 30 inch stride and it always

made us look stupid when we couldn't keep up with them. I'm not sure how

long I was at Ottawa but think it was until sometime in February. We were

assigned to different occupations at this basic training camp.

I was posted to Trenton, Ontario to become a clerk accountant

because of my training in the bank. We were there for the accounting course,

I think about 3 months when we got our first postings. We spent time in

regular classrooms but we also spent considerable time in the drill hall

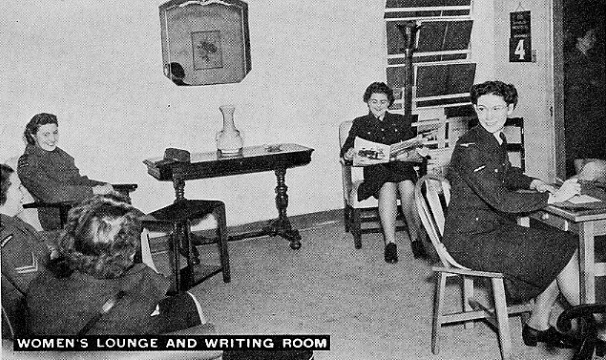

becoming proficient marchers. We were also given time off and there were

good facilities for amusements, bowling, cards, table tennis to name a

few. I'm sure there were some station dances but I don't remember them.

There would be concerts at times and we were all required to attend church

parades, these of course you were given the choice of religious ceremony

depending on your affiliation. At the end of our training we were required

to write an exam and if you were successful you were given the next posting.

I was sent to No.1 'Y' Depot in Halifax, N.S. This was the embarkation

depot where all the air force personnel reported before going overseas.

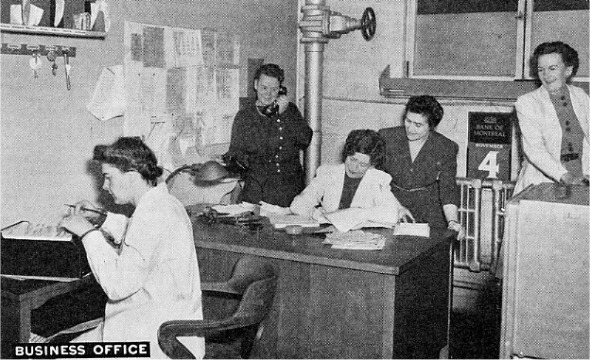

There were two sections in the accounting department, one was Pay Accounts

and I believe the other was more or less keeping track of inventory.

I was always in pay accounts, we kept track of the pay ledgers and on pay

parades checked off the names of the airmen and women who were being paid.

The individuals would line up and as they approached us would give their

rank, name and number so we could check their name off to be sure they

were receiving the correct pay envelope.

The Senior Accounting Officer would have the money on

hand and if the names and numbers corresponded with our records the money

would be counted out and handed over to the recipient. Since I was a payroll

clerk as such I got to see anyone from Delburne or elsewhere when we gave

them their last pay packet before they left for overseas,

Halifax was very interesting, this was the first time

I had been near the sea and I loved it. The street cars in Halifax were

very interesting to ride on, we'd nearly have a fit going down some of

the steep hills we were sure the street cars were going to go flying off

course. Service personnel would sing all the wartime songs as you travelled

to and from the downtown area. The ships in the harbour were fascinating

to a prairie girl and I walked many miles sight-seeing. There was lots

to do on the airbase, I went to several dances but it was all jitter-bugging

and I had never learned so was mainly a spectator. I was in Halifax for

ten months and then was posted to No.1 G.R.S. (General Reconnaissance School)

at Summerside, P.E.I. In the beginning of my Air Force career I made no

close friends as we were busy with course work etc. but when I moved to

Summerside life was quite different.

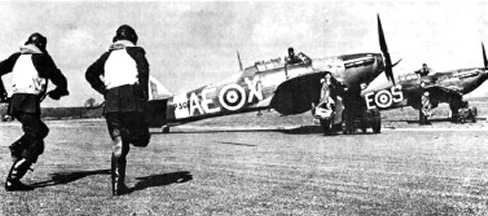

This was an active flying base so we had planes flying

in and out above us all the time. You soon got used to the noise and sometimes

wouldn't even bother to look up. I lived in quite a large barrack block,

the barracks were in the usual 'T' formation, near the front there was

generally a Corporal or Sergeant in charge of the barracks.

On our side there would have been at least 60 girls, there

were double bunks with an open isle between. I generally chose an upper

bunk, my best friend was below me.

Now that I look back our friends were mostly the ones

that were very close to you in the barrack block, a lot of them in the

accounting section but we also had vehicle drivers, cooks, domestic duty

girls etc. The nurses all had senior rank so they were in the Officers’

Quarters. The ablutions were in the cross-section of the 'T', we all did

our own laundry except the majority of us sent our shirt collars to the

Chinese laundry. Our shirts had detachable collars so these came back white,

white and stiff as a board. We had many a sore, raw neck but they did look

nice. As I recall we were given a small clothing allowance to buy our own

undies but everything else was supplied. This may be a good time to explain

our pay, we were given 90 cents a day but of course this was in addition

to room and board. This actually was considered excellent pay, an example

of pay before I joined the bank was helping at a farm home. I would walk

3 miles to get there and would work 8 or 9 hours and would only receive

75 cents for the day’s work. I can't remember what I received at the bank.

After a period of time in the Air Force or after satisfactory work we were

given an extra 5 cents per day. Reclassification to another rank gave you

more money.

I sat near the counter at work and nearly always waited

on anyone who came to make enquiries. Wing Commander Scott was in charge

of our Department, Flight Sergeant Pullam was my immediate boss. There

was a Sergeant and 2 Corporals in our office, these were all men and there

would have been approximately10 or 12 of us girls. The D.R.O.'s were the

daily news postings that we received each day and from these we changed

the pay amounts, reclassification etc. to the records for which we were

responsible, I always enjoyed my work.

One of the highlights for me was going for a plane ride,

arrangements were made for anyone that was on the air-base to have one

free ride if we so chose. One of our male Corporals, Cpl. Glenn Johnston

(a very nice older, married gentleman) and I went on the same plane. The

pilot flew us to Charlottetown and back, I sat next to the pilot and this

crazy guy decided I should see the steeple on the church in the small village

of Kensington. He dove down and me with my weak stomach, my stomach came

up and I knew I was going to be sick. I quick opened the window and stuck

my head outside, it was raining but that didn't stop me from being sick.

The rule in the air force was that if you were sick you washed the aircraft,

fortunately the rain washed everything off so I was saved the chore of

cleaning the plane. My treat of a special ride didn't sit too well but

I was glad I went. I know I spent several hours in a link trainer but I

have no idea why unless it was just to give us an idea of what real flying

was like.

There was no segregation between the men and girls in

the mess half and we were treated as equals in all circumstances.

I can't remember anyone discriminating between us. The Officers had their

own area for eating and sleeping and of course the order of the day was

to always salute an officer wherever you met them providing you were both

wearing your hat. We wore uniforms whenever we were on duty, when in the

barracks we were free to wear whatever we chose unless there was to be

an inspection. We spent hours polishing badges, shoes etc. and our bunks

had to be properly made up at all times. A lot of girls (and men) had difficulty

tying their tie so if they got it correct they generally just tied a slip

knot and put it around their neck and pulled the knot so they didn't have

to start from scratch. We had ironing boards in barracks but very seldom

used them, our uniforms held their press very well so they must have been

made out of quite good material.

One day my girlfriend Peggy MacEachern and I hitch-hiked

to Charlottetown a distance of less than 100 miles. It took us all day,

we rode in wagons, old vehicles, anything that moved. We came back by bus,

there were just so few vehicles in P.E.I. at the time. I think we stayed

at the Y.W.C.A. and we definitely toured the Parliament buildings.

Periodically we were given a 48-hour pass, I was too far

from home to ever get home but some of the girls that lived closer would

get home. We had one barrack mate that would bring back cooked lobsters,

I had never been exposed to such a thing but it was interesting. She would

bring these back and we would hammer them with some tool to break them

open and then the feast would begin. I wasn't a very good participant until

I acquired a taste for them but now I enjoy. The town of Summerside was

about six miles away but there was good bus service from the base. Sometimes

we would go into town but most often we were content to stay on the base.

We had badminton, bowling, pool and various other activities. There were

always picture shows and a few dances.

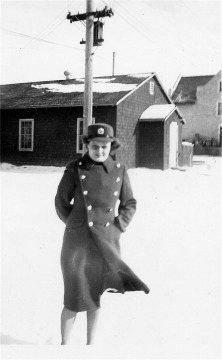

The only other thing of note while I was stationed in

Summerside was in the winter of 1944, we had terrific snow storms and the

snow banks reached up to the telephone wires. We were just a bunch of kids

and had lots of fun climbing the big snowbanks and sliding down. I don't

know what we used for clothes as we pretty well only had our uniforms.

We must have had a few civilian articles of clothing.

Dave came back to Canada in May of 1944 and we met in

Moncton and were there for 'D-day, June 6, 1944, when the allies invaded

Europe so we listened for war news. I booked into the 'Y' and got a room

at the hotel for Dave. We had corresponded all the time Dave was away and

sometimes we wrote nice letters and sometimes we found things to quarrel

about but eventually things worked out and we took up our relationship

as it had been before enlisting. We spent most of the time in Moncton sitting

through picture shows at the theaters. At this time we decided we would

get married in September at Summerside.

Dave went on to Debert, Nova Scotia for his new posting

and instructing on Mosquitoes and I went back to Summerside. Back in those

days one had to have permission to marry if you weren't 21 years of age.

I had been away from home for over two years but the law still applied.

Can't you hear what young people today would say about that. My Flight

Sergeant said he would forge my Dad's signature but I just couldn't cheat

so wired my Dad for permission. The Women's Division Commanding Officer

helped by taking charge of and getting the hall and the goodies for the

reception. I booked the minister and the church and Dave didn't meet Rev.

Jarvie until he came over the day before the wedding. Sgt. Hap Pullam gave

me away, F.O. Alexander Gibbard, Dave's friend was to be best man but he

got posted back overseas just before the wedding so one of my co-workers,

Cpl. Jeffrey filled in. I changed my name from McDowell to Pengelly and

life continued as before.

A posting came through for me to go overseas that fall.

They asked me if I wished to go and of course I was gung ho so I went to

Lachine, Quebec in preparation to going overseas. Dave was furious, he

would ask to go back overseas if I went, not very fair as he had been over

and why shouldn't I go. Anyway it was taken out of our hands, about that

time the war had progressed and was winding down so the Air Force decided

married women would be discharged. This was later rescinded and married

women could stay in but by that time I had already received my discharge.

I reported to Halifax where I received my discharge papers on February

2, 1945.

Frank

Bollman was born and raised in Moline Manitoba in 1922. He was one of those

farm boys who wanted to be a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force and

joined up in 1942.

Frank

Bollman was born and raised in Moline Manitoba in 1922. He was one of those

farm boys who wanted to be a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force and

joined up in 1942.