117

of 150: Training at No. 1 Central Navigation School - Rivers Manitoba

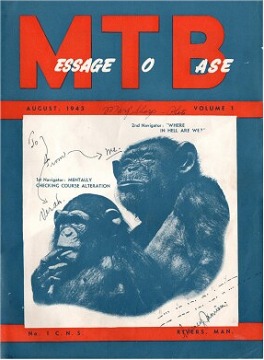

The following article was published

in the introductory issue of Message To Base – Volume 1, No. 1, August

1943, station magazine of No. 1 Central Navigation School in Rivers Manitoba.

It explains the unique role this school plays in the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan not only teaching new students the art and science of

navigation, but teaching others to teach navigation in a number of other

BCATP schools.

INTRODUCING G.I.S.

G.I.S.,

which, being interpreted means Ground Instructional School, is the

backbone of No. 1 C.N.S.(Central Navigation School). Therefore it was our

choice this month ahead of all other sections to feature in the initial

issue of M.T.B. (Message to Base). It is our intention to feature

a different section each month with a view to familiarizing everyone with

the station as a whole.

G.I.S.,

which, being interpreted means Ground Instructional School, is the

backbone of No. 1 C.N.S.(Central Navigation School). Therefore it was our

choice this month ahead of all other sections to feature in the initial

issue of M.T.B. (Message to Base). It is our intention to feature

a different section each month with a view to familiarizing everyone with

the station as a whole.

G.I.S. is the seat of learning for student navigators

coming to No. 1 C.N.S. for 20 weeks of instruction, as well as for bomb

aimers who come from B. & G. (Bombing & Gunnery) Schools for a

final six week course prior to graduation. In addition, there are four

specialist courses known as the S.N.I.N.'s, SNIP's, N.I.'s and E.O.'s.

SNIN's are graduate navigators who take a one month course here in specialized

subjects and instructional technique. From here they are sent to the various

Air Observer Schools in Canada to give instruction to student navigators.

They are under the supervision of F/L Minton, F/L Murray, and F/O Smith.

The SNIP's are graduate pilots taking a two month course

in navigation, after which they will be sent to Service Flying Training

Schools to instruct student pilots in navigation methods. F/O Watson and

F/O Maxwell are in charge of these courses. The N.I.'s come mostly direct

from Manning Depots for a 14 week course in navigation, following which

they are posted to Initial Training Schools. In charge of them are F/L

Weaver and F/L Solin. The E.O.'s are educational officers who come to us

from I.T.S.'s for a two month course in navigation. F/L Wellbourne and

F/O Tanner are the officers in charge of this course.

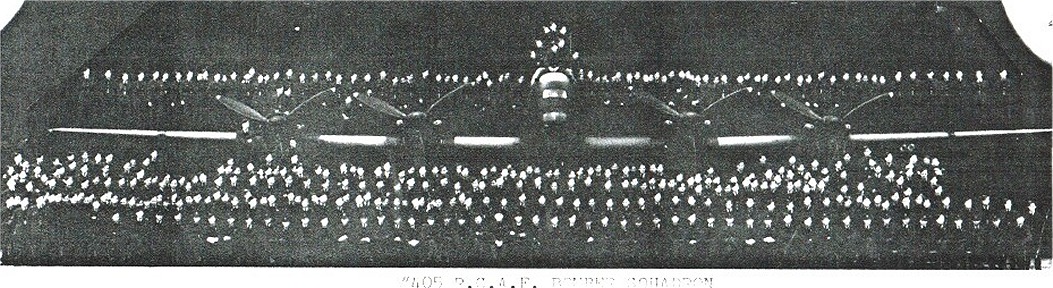

There are a large number of student navigators under training

at all times, for the most part members of the R.A.F. (Royal Air Force),

and in addition, several Air Bomber courses. Each of these courses is supervised

by a navigation instructor who is responsible not only for their instruction

but also for their general welfare, recreation, and discipline.

The most looked forward to thrill, generally, on the part

of the navigation students is flying. It is quite a surprise to many of

them to find their practical navigation is confined to the Synthetic Dead

Reckoning Trainer for the first four weeks. In these trainers navigators

and Air Bombers learn how to put into practice on the ground the navigation

methods they will be using in the air. The rooms are in total darkness

except for a small light over each table, as in an aircraft, and by use

of projections on the screen they are required to pin-point themselves,

using Topographic maps. They must also familiarize themselves with all

navigation methods. In addition to the normal navigation instruments, the

trainers are equipped with drift recorders, altimeters, air speed indicators,

compasses and radio loops. Even rough weather conditions can be duplicated

in operating the drift recorder. The value of these Synthetic Trainers

is their inexpensiveness in comparison to operating an aircraft. They also

familiarize the students with navigation instruments, methods, etc. They

are a real advantage for the instructors who may watch their students navigate

step by step, correcting on the spot any particular faults.

Everyone on the station is familiar with the sight of

navigators shooting celestial bodies by means of the Sextant. The Sextant

is a very delicate instrument by use of which the altitude of heavenly

bodies may be measured. The time to the nearest second that the shot is

made must be known. By referring to tables a line of position can then

be calculated for use in navigation. To become proficient in the use of

a Sextant the student navigators must take some 450 shots in twenty weeks,

each one of which must be plotted. In the near future student navigators

will be able to navigate under almost perfect air borne conditions in the

new celestial link trainers. In these trainers the celestial bodies are

represented by projections on the ceiling, enabling the students to shoot

them with Sextants.

The big job of supervising these courses is the direct

responsibility of S/L McKillop, C.G.I. (Chief Ground Instructor), the assistant

C.G.I., F/L Derry, and a large staff of instructors. The instructors have

been selected firstly, because of their ability as navigators, and secondly

because they possess the knack of telling others. Some of them are former

teachers, but the majority come from all walks of life. They are doing

a fine job as a body and their work, coupled with the application, industry,

and enthusiasm of the students, results in a steady flow of graduate navigators

from No. 1 C.N.S. every two weeks year in and year out.

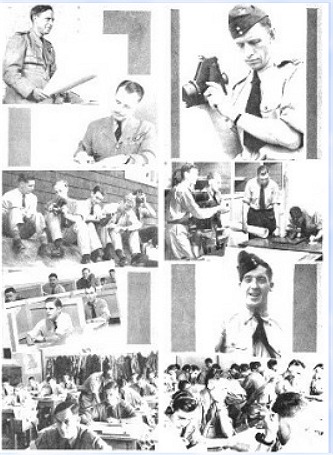

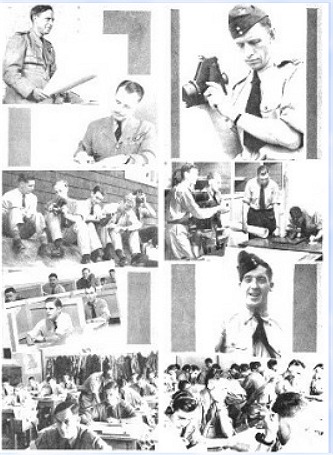

CAPTIONS

CAPTIONS

S/L A. F. McKillopp, Chief Ground Instructor, was snapped in a jovial

mood.

F/L Arthur Hammond, Adjutant of Training Wing.

Shooting the sun in style.

Such comfort couldn't be duplicated in the air, boys.

Bomb Aimers learning to map read on the ground.

F/O Buckley is seen instructing some student navigators.

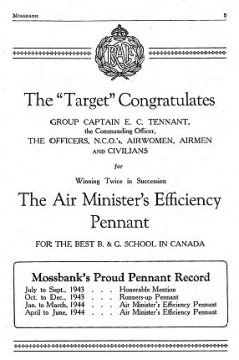

No.1 C. N. S.

F / L D. R. Derry, Assistant Chief Ground Instructor,

is shown checking his watch just before taking a sun shot.

Learning how to navigate on the ground via the Synthetic D. R. trainer.

Sgt. Dixon needs no introduction at No. 1 C. N. S.

DIDIT - DA - DA - DA ... and so on far into the day.

Cover page caption:

1st Navigator (monkey on the left): MENTALLY CHECKING COURSE ALTERATION;

2nd Navigator (monkey on the right): WHERE IN THE HELL ARE WE?

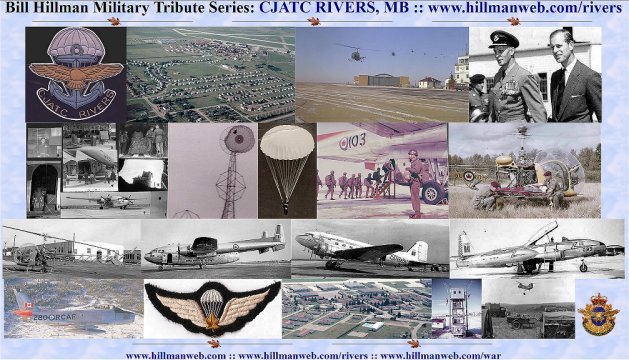

Peruse our 11 pages of post-war River Base at:

www.hillmanweb.com/rivers

Click for full-size collage

118

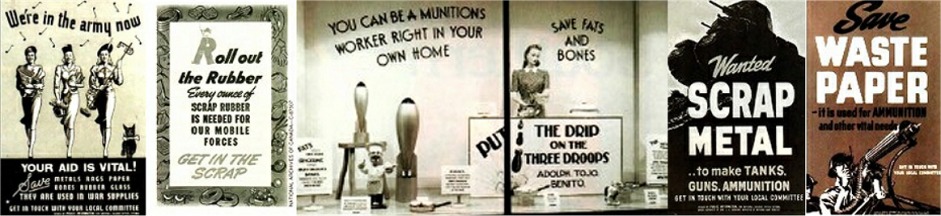

of 150: The Home Front: The Scrap That Made the Difference

Legion Magazine, November/December I998

Canadian Reflections – The Scrap That Made a Difference

By James M. Whalen

ln 1982, the first blue box hit the curb in Kitchener, Ont.,

and shortly thereafter the initiative for recycling waste material spread

across Canada. As the three Rs -- Reuse, Recycle and Reduce -- became catchwords

of the environmental movement, Canadians underwent a change in attitude.

Many materials previously thought of as trash were recycled rather than

thrown away. In fact, what happened in the 1980s was strikingly similar

to the recycling fervor that occurred much earlier during WW II.

Early in 1941, the federal government launched the National

Salvage Campaign to encourage patriotism of Canadians on the home front.

But, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the situation

changed because the supply of raw materials from the Pacific was disrupted.

This left North Americans short of rubber, tin, vegetable oil and other

resources.

Similarly, a shortage of Canada's own raw materials gradually

developed due to the lack of manpower to provide them. As the demand for

primary goods for war production increased, the federal government encouraged

Canadians to conserve and salvage various materials for conversion into

airplanes, tanks and other weapons. Although scarcity in Canada during

wartime was not nearly as severe as in Europe, the shortages led the Canadian

government to ration tires, gasoline, alcohol and some foodstuffs.

The National Salvage Campaign operated under the Department

of National War Services with a few paid organizers, including a headquarters

staff of about a dozen, in Ottawa, and about 20 provincial officers. But,

it mainly relied on an army of volunteers who formed voluntary committees

throughout Canada to salvage needed materials. The Department of National

War Services co-ordinated the work of these committees and advised each

group on what was wanted and the prices paid for various materials. The

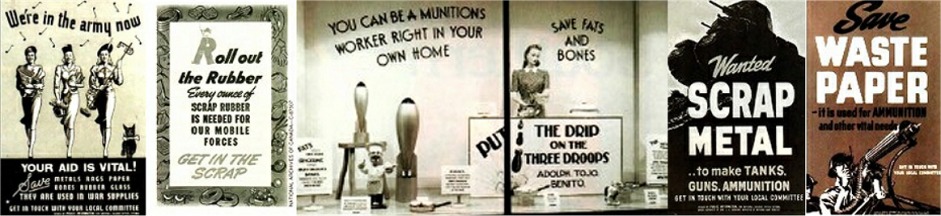

same department promoted salvage campaigns and informed the public about

collecting scrap by issuing pamphlets, posters, radio and newspaper advertisements.

To encourage the salvage effort, it used catchy slogans such as: Dig In

and Dig Out the Scrap, and Get Into The Scrap.

Salvage committees were required to register with National

War Services under the War Charities Act. Any profits they made had to

be spent on concerts, entertainment, recreation, hospitality, information

centres, canteens and on other war charities.

In several urban municipalities across Canada, voluntary

organizations joined together to form citizens' committees to co-ordinate

all war auxiliary services. One subcommittee of the citizens' group supervised

salvage on a block plan, that is, a particular town or city was divided

into zones or blocks each with a leader. Salvage items were then collected

by following the regular municipal garbage collection, much like the current

recycling pick-up

In March 1942, Charles LaFerle became the director of

the National Salvage Campaign. He had successfully co-ordinated the salvage

efforts of the Toronto Citizens' Committee, and believed that the block

plan was the soundest and most economic way of proceeding. As an example,

he pointed out that the Winnipeg Patriotic Salvage Corps, by using the

block plan, had collected over one million pounds of scrap materials in

a single month. ''The Winnipeg Corps is one of the strongest, most aggressive

and most enterprising of the 1,750 voluntary salvage groups operating throughout

the Dominion," he said.

Besides volunteer citizens' groups, others such as the

Boy Scouts, Girl Guides. Salvation Army and The Canadian Legion salvaged

materials Religious groups, service clubs, women's groups and social

service agencies, as well as women at home and school children, also contributed.

Several individuals used their own vehicles to pick up scrap at a time

when both gasoline and tires were rationed.

Not surprisingly, the determination of some people to

assist in the war effort bordered on the extreme. For example, shortly

after the National Salvage campaign began. Mrs. M.E. Beaddie of the Imperial

Order Daughters of the Empire in Vancouver, and the secretary of that organization's

Memorial Silver Cross Chapter, suggested to her member of Parliament that

the copper plaques presented to mothers and spouses of men killed in WW

I be returned to the government for scrap. "As each plaque represents a

life," she wrote, "we should be very glad if they could ... help save the

lives of our husbands and sons."

In declining the offer, the Hon. Jan Mackenzie emphasized

that the salvage value would not warrant giving up what "must be among

their most treasured possessions."

In September 1941, the Red Cross conducted its own national

campaign for scrap aluminum which was needed for the manufacture of bomber

and fighter planes. Homemakers, school children and others contributed

to this drive. Movie theatres across Canada assisted in a novel way. In

exchange for a scrap of aluminum, a child earned free admittance to a matinee.

In Sydney Mines, N.S., for example, children left some 1,500 worn out aluminum

pots and pans at the cinema's box office.

Scrap dealers often purchased the salvage collected by

voluntary organizations and sent it to smelters and mills for reprocessing.

It was a logical way to proceed because dealers knew how to sort and prepare

materials for disposal. In order to deflect criticism that they were profiting

from the war effort, the scrap dealers, most of whom were Jewish, formed

the Canadian Secondary Materials Association in 1942. The association

co-operated with the government in monitoring the operations of its own

trade.

Besides the Department of National War Services, several

other government or Crown-owned wartime salvage bodies evolved - four within

the armed services alone. But, the most important ones were Crown corporations

such as Wartime Salvage Limited and the Fairmont Company that regulated

collections, set prices, found markets and, at times, purchased certain

essential materials for war production. In order to understand the importance

of some of the salvaged materials during the war, let's take a closer look

at the following items: Iron and steel. oil, fat and bones, rubber and

waste paper.

Iron and Steel

Early in the war, the public learned that scrap iron and

steel could be reused to produce tanks, airplane engines and ships. A parliamentary

committee on war expenditures reported in January 1943 that each soldier

"requires an average of 4,900 pounds of steel in the form of carried or

supported equipment."

In fact, the demand for steel was so crucial that by September

1942, the federal government made it illegal to retain more than 500 pounds

of steel that was not in use. Consequently, most industries scrapped surplus

or obsolete machinery and equipment.

Unwilling to rely on volunteers alone, Wartime Salvage

Limited, the Crown's scrap metal purchaser, established sites throughout

Canada for the deposit of scrap iron and steel. For example, it negotiated

with grain elevator companies in Western Canada to purchase scrap metal

from farmers, voluntary associations and junk dealers "on the spot" for

$7 a ton. Wartime Salvage then paid to ship it by rail to the foundries

and mills mainly located in Central Canada.

Similar subsidies provided for the shipment of scrap metal

from other non-industrial areas of Canada. But, in 1943 and 1944, nearly

200,000 tons of scrap metal came in from Western Canada alone.

Private industry, as well as government and volunteers,

gave farmers a chance to co-operate. Dealers for International Harvester

- a farm implement company - for example, encouraged farmers to donate

their old plows, binders and tractors for war purposes. Otherwise, farmers

received the going scrap rate of $7 a ton.

Through the promotional work of the Department of National

War Services, the response to the iron and steel drive was overwhelming.

By March I944, iron and steel supplies were sufficient and an organized

effort to collect this metal was no longer necessary.

Oil, Fat and Bones

In December 1942, a year after the main supply of vegetable

oil for North America was disrupted by war in the Pacific, the government's

Oil and Fat Administrator launched an appeal for animal fat and bones.

Promoted by the Department of National War Services, and addressed to women

in particular, the campaign even featured a Disney animation entitled Out

of the Frying Pan, Into the Firing Line. As Mickey Mouse and Pluto proudly

carried a can of fat to the butcher, the narrator claimed that: "A skillet

of bacon grease is a little munitions factory" because fat provided glycerine

for making explosives.

Domestic uses to which fat was directed included soap

making and commercial baking. Along with fat, industry wanted bones for

the manufacture of airplane glue and fertilizer. Although the government

paid about four cents a pound for rendered drippings, and one cent a pound

for fat, not enough was collected because it was just too messy for most

homemakers to bother with.

Rubber

Vegetable oil was not the only commodity to be cut off from

North America after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Crude rubber supplies

were also severely affected. Consequently, Canada restricted its rubber

reserves and reclaimed worn out rubber goods. In 1942, tire rationing for

the general public was applied to everyone except owners of essential vehicles.

The shortage led Canada and the United States to establish Polymer Corporation

to develop synthetic rubber.

Meanwhile, Fairmont Corporation, a Crown corporation that

controlled crude rubber supplies, began buying scrap rubber and stockpiling

it. Simultaneously, National War Services promoted the salvaging of rubber

on a massive scale. While tires for warplanes, army vehicles, and for essential

purposes continued to be produced from high quality rubber, scrap rubber

was mixed with crude rubber to make items for domestic use.

Voluntary salvage committees helped fill the rubber shortage

by taking used tires and tubes, rubber hoses, floor treads and bathing

caps to gasoline stations that served as reclaim centres. Carloads of scrap

rubber arrived at processing plants in Central Canada from across the country

because Fairmont Corporation partially paid the transportation costs.

The post office conducted a very successful scrap rubber

drive in rural areas of Quebec and Ontario in the summer of 1942. In a

fortnight, letter carriers collected over 1,900 tons, including some bumper

pads that over-enthusiastic children tore off docks and wharves much to

the dismay of cottagers.

Canadians were thankful in February 1944 when Polymer

Corporation -- the synthetic rubber company -- came into production. While

synthetic rubber did not replace natural rubber entirely, it nonetheless

meant that the salvaging of reclaim rubber became unnecessary.

Waste Paper

In the fall of 1941, waste paper shortages occurred in Canada

because laborers who normally cut pulpwood were enlisting for military

service. Fearing a shutdown of the pulp and paper industry, National War

Services informed the public and voluntary salvage committees about

the critical need. Wartime Salvage, which controlled the use of waste paper,

as well as scrap metal, set prices and directed supplies to mills that

agreed to pay part of the delivery costs.

By August 1942, the overwhelming response to the call

for waste paper resulted in a surplus of about 1,500 tons. The oversupply

was difficult to dispose of because the United States stopped buying our

waste paper. As the market for old newspapers and cardboard collapsed,

Wartime Salvage bought the surplus from volunteers and sold it to the mills

at a loss rather than harm long-term paper salvaging efforts.

As expected, the market for waste paper changed once again.

By December 1943, Wartime Salvage wanted a minimum of 19,000 tons a month.

National War Services promoted the collection of waste paper throughout

Canada and got good results. Nonetheless, waste paper continued to be desperately

needed. In April 1944. the government increased the demand to 20,000 tons

a month stating that "a shortage may jeopardize our whole war effort."

Well before the June 6, 1944, Allied invasion of Normandy,

the minister of National War Services, General L.R. LaFleche, made it quite

clear that the public would have to collect a lot more paper for

the war effort. "We will need paper containers to be thrown overboard for

landing operations, to carry medical kits, blood plasma, emergency

rations and gas masks. We need paper parachutes to carry food to isolated

men, containers to make liners for such solvents as naphtha and benzene."

Consequently, the response to waste paper drives late

in the war was outstanding. For example, a civil service campaign in Ottawa

netted 458 tons. But that was little as compared to a three-day campaign

held in Toronto in March 1945 when volunteers collected an incredible total

of 1,400 tons.

Even though waste paper shortages continued after VE-Day,

the federal government soon quit the salvage business. However, the government

continued to pay part of the transportation costs for waste paper up to

the end of 1945. With the war over, waste paper was still needed especially

for housing, but supplies of pulpwood and lumber were still short. The

mills became so desperate for supplies that for several months they relied

on their own organization to oversee waste paper collections.

* * *

The war on waste on the home front officially ended in September

1945 when the Salvage Division of National War Services closed. Curiously

enough, during the 4 1/2 years of the division's existence, its headquarters

staff in Ottawa occupied one of the federal government's newest and most

prestigious buildings -- the Supreme Court of Canada, while the judges

remained in dilapidated quarters.

The irony of the situation was not lost on Jean-Francais

Pouillot, the member of Parliament for Temiscouta, Que., who frequently

raised the subject in the House of Commons. and in March 1944 remarked:

"There is no other country in the world where a beautiful and sumptuous

building built for the Supreme and Exchequer Court is serving as offices

for recuperation and salvage bodies, while the old building that would

be fit for recuperation and salvage bodies is serving as the location for

the highest court in this country."

With the return of peace in 1945, salvage operations soon

reverted to a prewar basis -- a multi-million-dollar business conducted

mainly by scrap dealers and as a fund-raiser for a handful of charitable

organizations. Less than a decade later, the public fervor for conserving

and reusing scrap materials had all but vanished. In a 1994 article in

National Geographic magazine, writer Neil Grove observed: "As the postwar

economy boomed and memory of sacrifice faded, our cast-offs graduated to

a country dump."

This is exactly what happened here in Canada and attitudes

did not change until recently. Unlike the early 1940s, it is environmental

concerns. not the necessities of war, that are forcing us to again practise

recycling.

While making his rounds in rural Ontario, a mailman collects items

for wartime recycling.

Scrap rubber was often mixed with crude rubber to make items for

domestic use,

while quality rubber had more specific wartime applications.

SALVAGE POSTER GALLERY

Click for larger full-size images

G.I.S.,

which, being interpreted means Ground Instructional School, is the

backbone of No. 1 C.N.S.(Central Navigation School). Therefore it was our

choice this month ahead of all other sections to feature in the initial

issue of M.T.B. (Message to Base). It is our intention to feature

a different section each month with a view to familiarizing everyone with

the station as a whole.

G.I.S.,

which, being interpreted means Ground Instructional School, is the

backbone of No. 1 C.N.S.(Central Navigation School). Therefore it was our

choice this month ahead of all other sections to feature in the initial

issue of M.T.B. (Message to Base). It is our intention to feature

a different section each month with a view to familiarizing everyone with

the station as a whole.

CAPTIONS

CAPTIONS