022 of

150

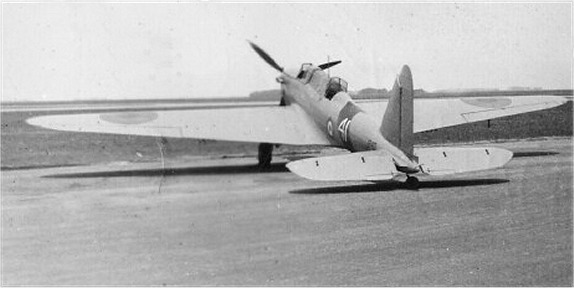

A World War II Memory: Mary Ellis - Air Transport

Auxiliary Pilot

A

wonderful newspaper article in Britain’s The Mail on Sunday was brought

to our attention by Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum charter member

John Robinson. It is the story of Mary Ellis, a veteran of the World War

II’s Air Transport Auxiliary, who celebrated her 100th birthday earlier

this year. The Mail on Sunday relayed her story and a video of her taking

control of a Spitfire aircraft, flying in formation with one she had flown

in WWII, over West Sussex in October of 2016. The complete story can be

seen at:

A

wonderful newspaper article in Britain’s The Mail on Sunday was brought

to our attention by Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum charter member

John Robinson. It is the story of Mary Ellis, a veteran of the World War

II’s Air Transport Auxiliary, who celebrated her 100th birthday earlier

this year. The Mail on Sunday relayed her story and a video of her taking

control of a Spitfire aircraft, flying in formation with one she had flown

in WWII, over West Sussex in October of 2016. The complete story can be

seen at:

http://www.mailonsunday.co.uk/news/article-4191976/Woman-flew-spitfires-WWII-celebrates-100th.html

A comprehensive accounting of the Air Transport Auxiliary

is available from Wikipedia at from which the following excerpts are offered

below.

The Air Transport Auxiliary was set up in the United

Kingdom in February 1940 with the primary objective of providing working

aircraft to the Royal Air Force. In doing so, the ATA ferried new, repaired

and damaged military aircraft between various destinations for deployment

by the RAF and manufacturing, repair or scraping locations. The ATA also

provided some air ambulance services and ferrying of service personnel

from one place to another. The ATA worked out of 14 ferry pools dispersed

throughout Britain. The organization also had an Air Movement Flight Unit

and two training units. Personnel included 1,152 male pilots and 166 female

pilots, 151 flight engineers, 19 radio officers, 27 cadets and 2786 ground

staff. By 1943, the women’s pay was equal to that of the men.

In World War II, the Air Transport Auxiliary flew 415,000

hours and delivered 309,000 aircraft to various locations. These numbers

include 147 types of aircraft including Spitfires, Hurricanes, Mosquitoes,

Lancasters, Halifaxes and Flying Fortresses. About 883 tons of freight

was carried and 3,430 passengers were transported without any casualties.

One hundred and seventy-four male and female pilots were killed flying

for the ATA.

As a civilian organization under the control of the Ministry

of Aircraft Production, the ATA relied on pilots who were not suitable

for the Royal Air Force or Fleet Air Arm service because of age or physical

fitness. Other pilots were recruited from 28 neutral countries.

Women from Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South

Africa, the United States, the Netherlands Argentina, Chile and Poland

were accepted into the ATA. Fifteen women lost their lives while flying

for the ATA. The women were initially restricted to trainers and transports

but went on to fly all types of aircraft used by the RAF and Fleet Air

Arm with the exception of the largest flying boats.

Although the ATA was a civilian organization, personnel

wore uniforms and pilots were given ranks equivalent to RAF ranks. These

were

ATA Senior Commander – RAF Group Captain

ATA Flight Captain – RAF Squadron Leader

ATA First Officer – RAF Flight Lieutenant

ATA Second Officer – RAF Flying Officer

ATA Third Officer – RAF Pilot Officer

The great contributions of the men and women of the ATA,

of which the release of eligible men to service in the RAF and Fleet

Air Arm was their biggest victory, surely helped to hasten the Allied victory

of World War II.

Wikipedia – Air Transport Auxiliary https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_Transport_Auxiliary

023 of

150

BCATP: Training -- The Morse Code

This eight page pamphet was received

at the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum in June 2015. In World War

II, It was given to potential RCAF air crew students in the Manning Depots

to give them a jump on one of the subjects they would need to learn in

advanced training. Admittedly, the Morse Code is a somewhat dry subject

but a read of the text translation below will definitely provide some intersting

points about the techniques and philosophy of Morse Code usage, an invaluable

communication skill required for aerial combat.

AIR FORCE PAMPHLET No. 11

(August, 1941)

DOMINION OF CANADA

The Royal Canadian Air Force

THE MORSE CODE And How to Learn It

NO'l'E

This pamphlet is issued to all recruits on posting to

Manning Depots for training as pilots, observers and wireless operators

(air gunner). Its object is to allow men to get a start with the Code in

the correct system prior to their courses of instruction. Use this continually

and bring it with you when you are transferred to an Initial Training or

Wireless School.

(Based on RAAF. Publication No. 81)

30:\1- 3-42 (1787)

H.Q. 560-11

THE MORSE CODE

INTRODUCTION

In

1836, Samuel Morse, an American, introduced the code system which bears

his name, and the first message by using the "Morse Code" was sent by telegraph

from Washington to Baltimore in 1844. The introduction of the Morse Code

was a tremendous advance in signalling, since it meant that communication

was no longer restricted to persons within sight of each other, but messages

could now be sent day or night over long distances. Although the code invented

by Morse was satisfactory for telegraph work certain difficulties were

encountered with the rapid: advance of radio or wireless telegraph as it

was called and at a convention in London in 1912 a new code was introduced,

known as the "International Morse Code". This covers all the languages

that use the Roman alphabet-English, French, German, Spanish, etc. The

"International Morse Code" is the code used in the R.C.A.F. for signalling

by means of wireless telegraphy. The international Morse Code can also

be used to signal by visual means (Aldis lamps) and by sound (Klaxon horns

for use in fog).

In

1836, Samuel Morse, an American, introduced the code system which bears

his name, and the first message by using the "Morse Code" was sent by telegraph

from Washington to Baltimore in 1844. The introduction of the Morse Code

was a tremendous advance in signalling, since it meant that communication

was no longer restricted to persons within sight of each other, but messages

could now be sent day or night over long distances. Although the code invented

by Morse was satisfactory for telegraph work certain difficulties were

encountered with the rapid: advance of radio or wireless telegraph as it

was called and at a convention in London in 1912 a new code was introduced,

known as the "International Morse Code". This covers all the languages

that use the Roman alphabet-English, French, German, Spanish, etc. The

"International Morse Code" is the code used in the R.C.A.F. for signalling

by means of wireless telegraphy. The international Morse Code can also

be used to signal by visual means (Aldis lamps) and by sound (Klaxon horns

for use in fog).

The International Morse Code (which from now on we will

refer to as simply the Morse Code) is based on two types of signals which

differ in the time taken to make them, namely a short signal and a long

one, called respectively a dot and a dash. Letters, numerals and other

necessary signals are made up of various combinations of these dots and

dashes. The Morse Code has the advantage that, unlike the Semaphore Code,

It can be used with various types of signalling equipment which can be

selected to suit requirements. The use of this code provides a means of

signalling over short or long distances both by day and by night. In visual

signalling the dot and the dash may be represented by the exposure of a

light for short and long periods (The Aldis Lamp). In wireless telegraphy

the operator makes dots and dashes by pressing for short and long intervals

a key, which actuates some form of electrical circuit. At the receiving

instrument the dots and dashes may be reproduced by short and long buzzes

on a telephone receiver or by means of musical notes of short and long

duration representing the dots and dashes of the Morse Code.

A wireless operator depends for his job, on his knowledge

of Morse Code. The standards required of aircrew in the R.C.A.F. are:

-

Pilots – Aural 8 w.p.m. - Lamp 6 w.p.m.

-

Observers – Aural 8 w.p.m. – Lamp 6 w.p.m.

-

Wireless Air Gunners – Aural 18 w.p.m. – Lamp 6 w.p.m.

The standards given above are the minimum standards required

on completion of training. Higher standards are required on operational

units after practice.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE CODE

Morse is a "sound language". To an operator, Morse symbols

speak as clearly as the spoken word. It depends on rhythm for its operation,

and it is important that it be appreciated as rhythm from the start. It

is usually written on paper in "dots and dashes." This is for the sake

of convenience in writing it down. Unfortunately, most learners attempt

to memorize the code in this form, It is easy to learn, and they have no

trouble in reading Morse at slow speeds - say up to 8-10 words per minute.

The reason is this. At these slow speeds, it is easy to pick out the dots

and dashes, count them up, and compare them mentally with the Code as it

was learnt, sort out the letter intended, and write it down. This, of course,

is a long and involved process and requires a certain agility of mind.

At speeds greater than about 10 words per minute, the

above process unfortunately becomes impossible and the learner, working

on this system cannot cope with the higher speeds. However, as the speed

increases, the ear gradually adapts itself to the increase in speed and

change of sound and, over 15 w.p.m. it learns to recognize the letters

themselves as sounds and not as collections of dots and dashes. Nevertheless,

it goes through a continual process of readjustment as the speed changes.

The process after this is much simplified. The ear hears

a collection of dots and dashes as a definite sound. This immediately registers

itself as a letter and is written down automatically, often without the

writer being conscious o! what he has written. It is clear, then, that

the person who learns the code as sounds to start with, need not readjust

his ear all the time as the speed increases, He also learns to write down

Morse sounds as letters instead of first having to translate them into

dots and dashes. A simple analogy is given here. The child learns its multiplication

tables by the singing method. This singing not only allows the child to

memorize the tables, but imprints them on the mind as a sound. - Ask yourself

the following simple questions-7 x 7, 7 x 8, 7 x 9-the answers come to

mind automatically without thinking. Now ask yourself 7 x 17, 7 x 18 -

you have to calculate them, as you have never learnt them before. In actual

fact, the simple multiplication tables are more than memorized. The sound

7 x 7, seven times seven, or however you learnt it, is part of a larger

sound, the remainder of which is 49.

In the same way, the Morse Code symbols should automatically

become letters. Thus didah brings to the mind "A" automatically - not didah

is dot dash, and that is ``A". It is possible, then, to learn Morse by

letters and not by dots and dashes and it is for the above reasons that

one should start with the correct method .and not with one of the various

methods often found in use. It is most important that the above principles

be studied and understood before proceeding further.

LEARNING THE CODE

The Code is easy to learn. One or two hours' concentration

will allow the student to master it, whether he learns by dots and dashes

or by any other method. Many students attempt to practise the code and

may practise for weeks without really knowing the symbols for all the letters.

This is merely wasting time. The student must ensure that he knows the

code thoroughly before attempting to practise it.

MORSE CODE IS EASY TO LEARN

When a child is taught to speak, it is shown an object

and the name of the object is repeated until the child is able to form

a mental picture of the object whenever the name of the object is mentioned.

Conversely, when the object is presented, the child is able to repeat the

name of the object and thus a WORD vocabulary is built up. A similar·

procedure is used to .learn the sound of letters,figures and punctuation

marks in Morse Code. Just as the sound of a word conveys to a child a mental

picture of an object, so· does the sound of a letter in Morse Code

convey to a wireless operator the letter it represents. It is imperative,

therefore that the sound of any letter, figure or punctuation mark should

always be sent the same way in Morse Code, with no variations. The first

step, therefore, in learning the Morse Code is to learn the proper SOUNDS

of the letters, figures and punctuation marks. THIS IS VITAL4Y IMPORTANT.

The sounds of all letters, figures and commonly used punctuation marks

are shown in this pamphlet. Memorize them, always making the same sound

for a particular letter, figure or punctuation mark. Do NOT one time say

da·didahdit, to represent the letter "C" and next time say da di,

dadit. In other words do not try .to SPELL out the. components of the sound

which represents a particular letter, figure. or punctuation mark - merely

repeat the sound as a whole.

THE IMPORTANCE OF TIMING OR RHYTHM

No one can write a sound but a standard set of symbols

can be used to represent the sounds of the Morse Code in the same way that

music is written, e.g. the letter "A" translated in to Morse Code consists

of an interrupted sound and is written Didah - the "Di" indicating a sound

is heard for a fraction of a second and the "Dah" that it is heard for

a slightly longer period of time. In their words, the SIN.GLE sound "Didah"

when sent at 5 w, p.m. or 25 w.p.m. always represents the letter "A" and

is always sent as "Didah" NEVER as "Di, Dah." If the transmitting wireless

operator sent "Di Dah", he would be sending TWO sounds. The receiving wireless

operator would translate these TWO sounds as "E.T." The interrupted sounds

representing the letters, figures and punctuation marks would always be

considered as SINGLE sounds NOT as several sounds joined together. For

instance when speaking the SINGLE word Canada, it is never broken down

into Ca na da, as it loses its word meaning. This timing or rhythm in making

the sounds of the Morse Code is very important and unless thoroughly understood

great difficulty will be experienced in becoming a first rate wireless

operator.

After reading and understanding clearly the remarks above,

the pupil can proceed to study the code. A glance at the code symbols (page

6) will show that the code is not written down in dots and dashes, but

in the form in which it sounds to the ear. This immediately eliminates

one mental process - that of translating it from dots and dashes to sound

or vice versa. It will also be seen that the sound is shown first and the

meaning second. It is important that the student should learn it in this

manner - a sound representing a letter and not vice versa: e.g., learn

that "didah’’ means ``A" and not "A’’ is ``didah". It will also be seen

that full emphasis is placed on the dashes while the dots arc slurred.

In other words, the tendency should be to stress the length of the dash

thus contributing to the rhythm. First, turn to (page 6) which shows the

code and cover up the column showing the letters of the alphabet. Second,

learn to sing the Morse symbols, slowly at first, and later faster and

faster. Nominally the time for a dash should equal that for three dots.

If you accentuate the dash you will get the idea much better. Try to slur

the dots together, and sing the symbol. Finally, uncover the letters and

discover the meaning of each sound after you learn to .sing it.

DO NOT ATTEMPT TO SEND THE CODE WITH A BUZZER OR BY

ANY OTHER MEANS AS YOU CANNOT HOPE TO MAKE THE SYMBOLS WITH A BUZZER UNTIL

YOU HAVE LEARNT HOW THEY SHOULD SOUND

You can actually learn Morse by this system up to 6 or

8 words per minute, or even faster, without ever hearing a Morse signal.

Continue singing the Morse symbols until you can’t sing the sounds any

faster. By this time, you will have got the idea of the rhythm of the code,

you will know it, and should be able to receive it. Try singing to yourself

Morse symbols for the, signs, oil billboards, street names, etc., as you

go about your daily duties. It is of the greatest importance that you get

an even flow in all your Morse characters and not a jerky or uneven sound.

Many of the letters become unreadable if they are not made correctly. One

of the chief errors usually arises in the letter "C". This is, of course,

dahdidahdit. Learners make various errors in this such as .dah dit, dah

dit, or dah, didah dit. the letter "F", dididahdit, - becomes di dit dahdit

- "L", didahdidit, becomes didah, didit, and so on. Concentrate on getting

a smooth and continuous sound and do not separate the elements of any Morse

symbol.

Next think of Morse as dots and dashes and avoid such

methods as learning opposites. You will find that, after a few days, Morse

letters come to you automatically and, by the time you are ready to start

serious practice, you will be well on the way to a speed of 8 to 10 words

per minute.

HANDWRITING

As the primary function of a wireless operator is to

translate radio signals into written words, he must be able to write a

neat, legible hand at fairly fast speeds. Try writing from dictation at

a speed of 25 words per minute (1 word equals five letters) and continue

practising until you can do this easily (writing with pencil only). Develop

a free easy style of handwriting, always using a pencil of at least 4 inches

in length, never smaller.

SPACING RULES FOR LETTERS, WORDS, AND GROUPS

(i) the dots and dashes, and

spaces between them, should be made to bear the following relation one

to another as regards their duration:

(a) A dot is taken as the unit.

(b) A dash is equal to three dots.

(c) The space between any two of the elements which form the same character

(letter, figure or symbol) is equal to one dot.

(d) The space between two characters is equal to three dots.

(ii) Any number and combination

of letters, figures or symbols signalled consecutively so as to form one

entity is termed a group. A group consisting of letters forming a word

in plain language is termed a word. The space between two groups or words

is equal to five dots (for speeds of 20 w.p.m. and over).

(iii) For speeds below 20 w.p.m.,

the space between characters and between words should be inversely proportional

to the speed, i.e. the slower the speed, the longer the space . The elements

forming each character must always be made at a speed which, with proper

spacing, is equivalent to not less than 20 w.p.m. This is necessary in

order to preserve the correct rhythm at slow speeds.

MODIFICATIONS TO MORSE SYMBOLS

(i) A horizontal line over letters

expressing a sign denotes that the elements forming these letters are made

as one Morse Code symbol and not as two separate letters.

(ii) The term "barred" is used

to denote any accent or modification to a letter. In describing a letter

phonetically the term "barred" is used after the letter, e.g., "A barred"

means an accented A, and is written A with a bar over it.

INTEREST IN MORSE CODE IS HALF THE BATTLE

If you learn the Morse Code in the manner just described

you will find it very interesting, and also your progress will be rapid

and sure, and, more important still, you will not forget it. It is, however,

very necessary to CONCENTRATE to the best of your ability during the Morse

Code instruction periods, as it is a MENTAL process and no one can learn

it for you. YOU are master of your own destiny. If you do not concentrate

your progress will then be slow-you will lose interest-your progress will

then be slower still and so on, until finally you begin to detest the Morse

Code instead of enjoying it.

MAKING MISTAKES

If, while receiving, you make a mistake or miss a letter

DO NOT get excited or try to think of the sound of the letter you have

missed. Relax and wait for the next sound and copy it. It is easier to

relax and wait for the next sound if your mind and writing hand are occupied

between the time the mistake is made and the next sound. A good way to

occupy yourself during this period is to make one or more "X's" where the

missing letter should be. This tends to prevent nervous tension and results

in less mistakes.

SENDING THE MORSE CODE

If you listen to good Morse sending at any speed you

will notice the rhythm. The dots and dashes bear the correct relationship

to each other and the spacing between the elements of each character, and

between characters and words, is in accordance with the principle laid

down in this pamphlet. Timing is the essence of good sending. Everyone

has listened to a mediocre piano player who THOUGHT he was making music.

It is the same with the poor sender - he THINKS he is sending Morse. Do

not try to judge the correctness of your sending yourself. If the other

fellow says it is bad, it IS bad. Do not be too anxious to practise sending

before you reach your first training unit. Instruction in sending must

be practical to be of value - it cannot be given in a pamphlet. You should

be able to receive at a speed of 6 words per minute or more before you

attempt to practise sending.

REMEMBER

There is only one person who can make you a first class

wireless operator, that is Y 0 U R S E L F.

THE MORSE ALPHABET

Sound

Meaning

didah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A

dahdididit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . B

dahdidahdit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . C

dahdidit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . D

dit , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,

, , .E

dididahdit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . F

dahdahdit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .G

didididit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .H

didit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . I

didahdahdah , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , J

dahdidah . , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , K

didahdidit , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , L

dahdah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .M

dahdit , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , N

dahdahdah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , , ,0

didahdahdit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , , , P

dahdahdidah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , , Q

didahdit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , ,R

dididi t . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , ,S

dah , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , T

dididah , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , U

didididah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , , ,V

didahdah , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,W

dahdididah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , , X

dahdidahdah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , , , Y

dabdahdidit. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , , Z |

NUMERALS

Sound

Meaning

didahdahdahdah , , , , , , , , , , , , , , 1

dididahdahdah , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , 2

didididahdab , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,, , 3

dididididah , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , 4

dididididit , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , 5

da.hdidididit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

dahdahdididit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

dahdahdahdidit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

dahdahdahdahdit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

dahdahdahdahdah , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,0

Erase Sign (eight or more dots)

Comma Sign III

Full Stop AAA

Commencing Sign VE

Ending Sign AR

. |

Copyright 2013. Greg Sigurdson. All Rights

Reserved.

024 of

150

BCATP Event: The Quebec Conference 1944

The Quebec Conference of 1944 was the

second meeting in Quebec City between British and American allies to discuss

military matters related to World War II. The major players at these conferences

were Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President of the United

States, Franklin Roosevelt. Respective staff members took part in the discussions.

The Quebec Conference took place between September 12 and 16 1944. Canadian

Prime Minister William Lyon MacKenzie King hosted the event and attended

a number of social functions but did not take part in the conference’s

scheduled discussions. Agreements were reached on the following topics:

-

Allied occupation zones in a defeated Germany

-

the Morgenthau Plan to demilitarize Germany

-

U.S Lend-Lease to Britain issues

-

the role of the Royal Navy in the war against Japan

The wives of Churchill and Roosevelt, Clementine and Eleanor

also attended the conference. A donation to the Commonwealth Air Training

Plan Museum yielded the accompanying photographs taken at the conference.

Photo captions with quotation marks are official press release captions

released with the photos at the time.

Wikipedia – Second Quebec Conference - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Quebec_Conference

Quebec Conference Photographs

Click for larger images

Top Men at Quebec

The President of the United States and the Prime Minister

of Great Britain together with combined Chiefs of Staff pose for photographers

on the Terrace of the Citadel at the conclusion of their joint conferences

in Quebec. Seated, left to right, are: General G.C. Marshall, Admiral W.D.

Leahy, the President, the Prime Minister, Field Marshall Sir Alan Brooke,

Field Marshall Sir John Dill. Standing at the back, from left to right

are: Major General J. Hollis, General Sir Hastings L. Lamay, Admiral E.J.

King, Marshal of the RAF Sir Charles Portal, General H.H. Arnold, Admiral

of the Fleet Sir Andrew B. Cunningham.

US President Franklin D. Roosevelt

. . . in his Presidential Automobile with Britain's Prime

Minister Winston Churchill astride the car, at the Quebec City train station.

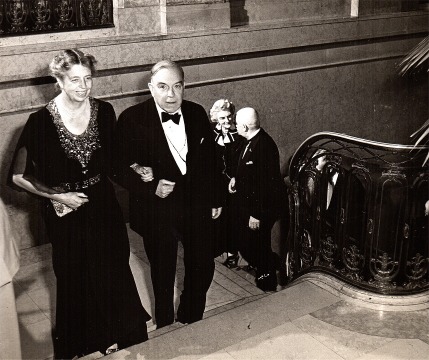

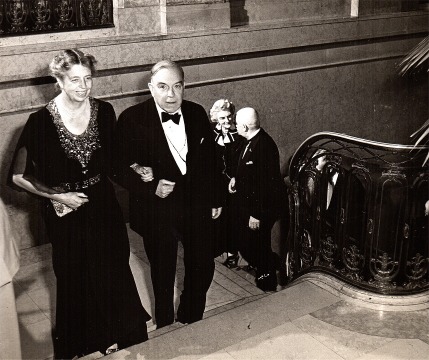

The Prime Minister's Reception

Following their guests up the broad sweep of the marble stairs

at the Chateau Frontenac the Prime Minister and Mrs. Roosevelt, followed

by Mrs. Churchill and the Lieft-Governor of Quebec, Sir Eugene Fiset, proceed

to the banquet hall, where they sat with more than 300 quests who attended

the Prime Minister's reception.

A Quiet Chat

Seated on the terrace at the Citadel overlooking the broad

sweep of the St. Lawrence below, Mrs. Churchill, wife of the British Prime

Minister, chats with Canada's Prime Minister as the two await the rest

of the party before meeting a battery of press and movie photographers.

A vigilant National Film Board photographer caught this exclusive photo.

On The Air

Speaking to the Canadian people over the CBC network, Elanor

Roosevelt and Mrs. Churchill chat together for photographers before they

deliver their messages. They spoke from the radio room of the CBC at the

Chateau Frontenac Wednesday evening, just before attending the reception

of Canada's Prime Minister there.

L-R: Air Chief Marshall Sir Charles Portal, (Minister

of Defence for Air) Air Marshal

C.G. Power, General Sir Alan Brooke, Wing Commander

Gibson.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Presidential automobile

passing the Cenotaph in Ottawa.

(There is no record that FDR visited Ottawa before

or after the 1944 conference.

He did visit Ottawa in 1943 after the first Quebec

Conference and this photo must be of that event.)

Winston Churchill and W.L. Mackenzie King

with Royal Canadian Mounted Police and gentlemen.

(4)

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King,

RCAF Air Chief Marshall Breadner and

Clementine Churchill at the Citadelle in Quebec City.

Old Friends Meet Again

First to greet the British Prime Minister on his arrival

in Quebec City for the Second Quebec Conference was Canada's Prime Minister

W.L. Mackenzie King, who boarded the Churchill train as it came to a stop,

welcomed Mr. and Mrs. Churchill to Canada. Then all three walked over to

the automobile of the United States President on an adjacent siding, and

the entire party proceeded to the Citadel, where they are guests of His

Excellency the Governor General and Her Highness Princess Alice during

the duration of the Conference. Photo shows Winston Churchill, Mr. King

and Mrs. Churchill as they proceed to greet the President.

Copyright 2013. Greg Sigurdson. All

Rights Reserved.

025 of

150

A World War II Memory: Cliff Shirley - Air Observer/Navigator

The following oral history was received

at the Commonwealth Air Training Plan museum in June 2001. In the letter

dated January 20 2001 that accompanied the donation, a man by the name

of Willie Freitag explained that Cliff Shirley, the author of the oral

history, met him while teaching Willie’s younger brothers in the school

in Alameda Saskatchewan. He said that Cliff taught school for four years

before joining the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940 and was now 87 years

old and as sharp as he was 60 years ago. When Willie told Cliff that the

museum was looking for `war stories,’ Cliff wrote his oral history which

he sent to Willie who then sent it to us.

Willie,

Willie,

I'd like to comply with your request for comments about

air force during World War by telling of several learning experiences.

I have nothing but praise for what the British Commonwealth Air Training

Plan (B.CATP) did for me. I graduated with an "Air Observer's Wing" (an

"O" ). The air observer course specialized in Navigation and Bombing with

a smattering of Gunnery, Wireless and Meteorology in stages of about sixteen

weeks each.

Prime Minister MacKenzie King demanded that control of

the training plan in Canada be administered by the Canadian government

and its Canadian graduates would maintain their Canadian identity when

sent overseas. The deal was made on MacKenzie King's birthday December

17/39. I still say congratulations to our former prime minister for that

memorable

agreement.

In the British Air Manuals, the Canadian Air Observer's

training for the handling of a responsible and exacting task, are commended.

About 1942 Commander Harris decided that Air Observer (0) be changed to

Air Navigator (N) because the task of navigation did not give the eyes

of the navigator time to adjust over the target to use the bomb sight accurately.

I think bombing was my favorite and a very successful part of our training,

but later, when new instruments were added to our job, I understood Commander

Harris' thinking. The organization by BCATP was superb--it almost seemed

our name was on our bunk before we arrived and our plate at a table was

waiting to be filled with good food .

During our training we moved about six times and had to

pass many tests in the air and at a desk. To tell the complete truth--the

best classroom we had was the inside of a bomber; the most useful information

we had was from the airmen who had just returned from a bombing raid. To

pass all air and ground tests gave our pride a big boost. To look at our

insignia gave us a feeling that we could succeed at any job in this new

career. In fact, we didn't know what fear was and acted quite "cocky.’’

Next came a posting to an operational training unit in

Yorkshire, England. What a difference -- larger and faster aircraft (Wellingtons),

a crowded and hostile air space and flying at night with little or no visibility

of the ground (everything was completely blacked out). The training was

quite concentrated and chatter among our airmen involved a bit of casual

bravado (to me that word means "fear"). At the end of this course, we were

sent to a crewing-up arena or posted to squadrons.

As for me, I saw two uniformed men approaching. The one

with the Wings (a pilot) said "We need a Navigator-Bomb aimer", the one

with the half wing (a wireless op) said "Our first Navigator was a "clot"·

Wow -- my imagination was my enemy, but I was on my way to membership in

a real RAF air crew on an RAF station in operational Manchester bombers.

These bombers had the reputation for not performing too well at high level

- with a heavy load of explosives. The air crew bonded well, the ground

crew were talented and all had very visible cheerful expressions. Our pilot

turned out to be a superman (we called him "Flash"). Most of our bombing

was done between two and four thousand feet and I learned to like to use

the bomb sight. All our trips were at night in a dark and hostile sky,

At the end of the first tour (30 trips) I was posted to

a test crew job. The crew was RAF, Our tasks were challenging but not too

risky. Many of the results were quite useable. In fact, we were treated

as sort of "gen" men flying a radial engine Lancaster bomber. Our pilot's

name was King Cole and he could play the part with gusty bravado using

a cockney accent. To be quite honest, I liked the "King" and he was a talented

pilot and captain. I learned a lot about navigation during this six months

and what I learned served us well; but – I ran into a problem.

With

success and experience came a promotion. I now moved to the British Officer's

area. When a young man brought up in a friendly farm environment in Saskatchewan

tries to adjust his culture to that practised by British officers, somebody

is going to be unhappy. I soon understood why MacKenzie King said Canadian

air men would keep their own identity. I couldn't understand how Royalty

could inspire men to be arrogant and haughty; I couldn't understand how

a rural Saskatchewan school teacher should be regarded as "dim, daft, and

difficult". I had chosen freely to join the RAF, and I proudly kept my

accent, vocabulary and behaviors. Time cures most problems, and I have

to concede that RAF airmen and ground crews were trained very well and

made determined efforts to hit their targets!

With

success and experience came a promotion. I now moved to the British Officer's

area. When a young man brought up in a friendly farm environment in Saskatchewan

tries to adjust his culture to that practised by British officers, somebody

is going to be unhappy. I soon understood why MacKenzie King said Canadian

air men would keep their own identity. I couldn't understand how Royalty

could inspire men to be arrogant and haughty; I couldn't understand how

a rural Saskatchewan school teacher should be regarded as "dim, daft, and

difficult". I had chosen freely to join the RAF, and I proudly kept my

accent, vocabulary and behaviors. Time cures most problems, and I have

to concede that RAF airmen and ground crews were trained very well and

made determined efforts to hit their targets!

We did our second tour in Lancaster Bombers at from 15,000

to 20,000 feet. We. (Flash and crew) did our share of Ruhr Valley bombing

and mine laying trips. We had one interesting trip when we bombed near

the toe of Italy, landed in Africa and bombed a city in northern Italy

on the way home. This seven hour trip was quite different to others.

English Commander Harris believed in concentrated bombing

of bombers in a short period of time, with a very large number of German

fighters who were dedicated and well trained; their air craft were almost

equal to Spitfires. Sometimes they entered our circuit when we were landing

or at takeoff.

The next line is hard to write. Good bye to our pilot

(Flash ). He was killed four days after completion of our second tour.

If God needed a talented, gifted and dedicated Englishman, his choice was

perfect, but heart breaking. I still ride my Raleigh bicycle that he liked

to borrow. I learned a lot from my ``hero".

Next came a posting to the BCATP at Rivers, Manitoba .

This course included instructional techniques, navigation and searches.

At the conclusion of this course we (my wife and I) went to Overseas Training

Unit at Boundary Bay, B.C., interacting and flying in Mitchells and Liberators.

Flying in friendly skies and unfriendly mountain peaks was a big change.

The students were mostly men who had completed one or more tours in the

European war and were crewed up

in preparation for Japan.

I can't say I enjoyed searches for airmen who didn't return

from flying over dangerous terrain. Most of our searches were failures.

I didn't look forward to what was to be bombing in the Asian area . I had

no regrets when peace was declared on Aug 14, 1945. If when reading the

honour rolls of Arcola-Kisbey and Carlyle, I think these districts in Sask.

lost more than their share of uniformed men.

To go from BCATP as a student and to return to BCATP as

an instructor requires a little luck. Whether we call it luck, or that

someone had me by the hand, or that BCATP did its job--I say this: Willie,

there's a silent "thanks" in every line I write. Writing the whole thing

brings back many sad memories. It's too cruel to believe that civilized

nations have to resort to war to settle arguments. The next conflict will

have weapons that could shake planet "Earth", but I am sure it will never

happen.

When we (my wife and family) went to teach school in Redvers,

one of the first men I met was Chris Sutter. He had an experience where

air space was very crowded. He is the sole survivor from two four engine

bombers that collided over enemy territory. He made a successful parachute

landing and in spite of a sore back, I am sure this airman also says a

few "thanks" and has many memories.

Willie,--I don't think there will be a volume two. I taught

school for many years. I hope the World War improved my abilities as a

teacher. I taught many wonderful school students. They were always good

to me. Those years I wish I could repeat.

Cliff Shirley

Weyburn Saskatchewan

Citation for the award of Cliff Shirley’s Distinguished

Flying Medal (from Hugh Halliday’s RCAF Honours and Awards database):

SHIRLEY, FS (now WO) Clifford Alvin (R79864) - Distinguished

Flying Medal - No.158 Squadron - Award effective 31 December 1942 as per

London Gazette dated 12 January 1943 and AFRO 232/43 dated 12 February

1943. Born in Carlyle, Saskatchewan, 1912; home there or in Ladner,

British Columbia (teacher); enlisted in Regina, 28 November 1940.

Trained at No.2 ITS (graduated 31 March 1941), No.3 AOS (graduated 23 June

1941), No.2 BGS (graduated 4 August 1941) and No.1 ANS (graduated 1 September

1941). Commissioned 1942. Invested with award by King George VI,

16 March 1943.

Flight Sergeant Shirley, as navigator, has

participated in many attacks on important targets in the Ruhr and the Rhineland.

He also took part in two of the attacks on Rostock, all three 1,000 bomber

raids on Cologne, the Ruhr, and Bremen, the highly successful attacks on

Genoa and the daylight raid on Milan. His standard of navigation

has invariably been of the highest order.

Throughout, this airman's conduct and determination

has set a fine example both in the air and on the ground.

Cliff died on May 12 2005 at the age of 92 years. Cliff’s

complete obituary can be seen at:

http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/leaderpost/obituary.aspx?n=clifford-alvin-shirley&pid=3540509

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

A

wonderful newspaper article in Britain’s The Mail on Sunday was brought

to our attention by Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum charter member

John Robinson. It is the story of Mary Ellis, a veteran of the World War

II’s Air Transport Auxiliary, who celebrated her 100th birthday earlier

this year. The Mail on Sunday relayed her story and a video of her taking

control of a Spitfire aircraft, flying in formation with one she had flown

in WWII, over West Sussex in October of 2016. The complete story can be

seen at:

A

wonderful newspaper article in Britain’s The Mail on Sunday was brought

to our attention by Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum charter member

John Robinson. It is the story of Mary Ellis, a veteran of the World War

II’s Air Transport Auxiliary, who celebrated her 100th birthday earlier

this year. The Mail on Sunday relayed her story and a video of her taking

control of a Spitfire aircraft, flying in formation with one she had flown

in WWII, over West Sussex in October of 2016. The complete story can be

seen at:

In

1836, Samuel Morse, an American, introduced the code system which bears

his name, and the first message by using the "Morse Code" was sent by telegraph

from Washington to Baltimore in 1844. The introduction of the Morse Code

was a tremendous advance in signalling, since it meant that communication

was no longer restricted to persons within sight of each other, but messages

could now be sent day or night over long distances. Although the code invented

by Morse was satisfactory for telegraph work certain difficulties were

encountered with the rapid: advance of radio or wireless telegraph as it

was called and at a convention in London in 1912 a new code was introduced,

known as the "International Morse Code". This covers all the languages

that use the Roman alphabet-English, French, German, Spanish, etc. The

"International Morse Code" is the code used in the R.C.A.F. for signalling

by means of wireless telegraphy. The international Morse Code can also

be used to signal by visual means (Aldis lamps) and by sound (Klaxon horns

for use in fog).

In

1836, Samuel Morse, an American, introduced the code system which bears

his name, and the first message by using the "Morse Code" was sent by telegraph

from Washington to Baltimore in 1844. The introduction of the Morse Code

was a tremendous advance in signalling, since it meant that communication

was no longer restricted to persons within sight of each other, but messages

could now be sent day or night over long distances. Although the code invented

by Morse was satisfactory for telegraph work certain difficulties were

encountered with the rapid: advance of radio or wireless telegraph as it

was called and at a convention in London in 1912 a new code was introduced,

known as the "International Morse Code". This covers all the languages

that use the Roman alphabet-English, French, German, Spanish, etc. The

"International Morse Code" is the code used in the R.C.A.F. for signalling

by means of wireless telegraphy. The international Morse Code can also

be used to signal by visual means (Aldis lamps) and by sound (Klaxon horns

for use in fog).

Willie,

Willie,

With

success and experience came a promotion. I now moved to the British Officer's

area. When a young man brought up in a friendly farm environment in Saskatchewan

tries to adjust his culture to that practised by British officers, somebody

is going to be unhappy. I soon understood why MacKenzie King said Canadian

air men would keep their own identity. I couldn't understand how Royalty

could inspire men to be arrogant and haughty; I couldn't understand how

a rural Saskatchewan school teacher should be regarded as "dim, daft, and

difficult". I had chosen freely to join the RAF, and I proudly kept my

accent, vocabulary and behaviors. Time cures most problems, and I have

to concede that RAF airmen and ground crews were trained very well and

made determined efforts to hit their targets!

With

success and experience came a promotion. I now moved to the British Officer's

area. When a young man brought up in a friendly farm environment in Saskatchewan

tries to adjust his culture to that practised by British officers, somebody

is going to be unhappy. I soon understood why MacKenzie King said Canadian

air men would keep their own identity. I couldn't understand how Royalty

could inspire men to be arrogant and haughty; I couldn't understand how

a rural Saskatchewan school teacher should be regarded as "dim, daft, and

difficult". I had chosen freely to join the RAF, and I proudly kept my

accent, vocabulary and behaviors. Time cures most problems, and I have

to concede that RAF airmen and ground crews were trained very well and

made determined efforts to hit their targets!