Bill and Sue-On Hillman In planning the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, Canada followed the American lead of exploiting cheap Chinese labour for the construction the most hazardous and costly section of almost 1,000 km through the mountains of the Western Cordillera in BC and Alberta. As in the US, many Canadian railway entrepreneurs would make vast fortunes on the backs of Chinese coolies. The indigenous First Nations population was not a viable source for workers since most were opposed to the construction of the railroad. They saw it as a threat to their lands and way of life.

Present

CHINESE IN CANADA I

www.hillmanweb.com/chinese/epic

An Epic Journey Across Three Centuries

Continued in Part II: Successes

CHINESE LABOUR IMPORTED TO WORK

ON THE CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY 1881

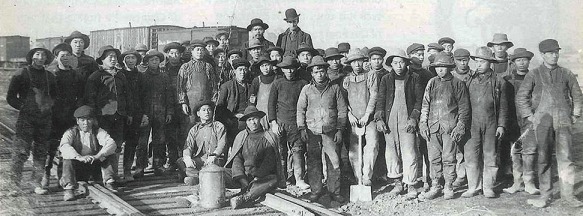

Over 17,000 Chinese came to Canada from 1881 through 1884 to work as labourers on this Trans-Continental Railroad. Several thousand came from the coastal areas of the United States where they had helped build the American transcontinental railroad, but the majority arrived directly from southern China. They encountered a hostile reception in British Columbia.

The province already had a sizeable Chinese population following the gold rush to Canada's "Gold Mountain" in the late 1850s, and racism towards the Chinese was widespread. Newspaper articles and editorial illustrations of the time repeatedly portrayed the Chinese in a degrading way. Many feared that Chinese workers, who were willing to accept lower wages, would take jobs away from white workers. Also, the Chinese culture was abhorrent to white Canadians who did not understand Chinese cultural practices in areas such as dress, living conditions, celebrations, spiritualism and even funeral rites.

After a long and difficult voyage across the Pacific Ocean, a short trip across the Georgia Strait to mainland British Columbia, and a boat ride up the Fraser River, the new arrivals disembarked at Yale where they would begin their work for the CPR. The treacherous Fraser Canyon and Hell's Gate lay north of Yale, and the river beyond the town was impossible to navigate. The rest of the journey to the work sites was on foot. Once the groups were formed they made their way to Lytton on uphill mountain trails with supplies suspended on shoulder poles or in large packs on their backs. Often holding onto a rope, they climbed in single file up the mountains to the work sites.

The Chinese workers died in landslides, cave-ins, from disease, drowning, explosions, malnution, inadequate medical care and the negligence of their supervisors. Blasting tunnels through the mountains of B.C. made it the most dangerous, time-consuming, and deadly section of the railroad. Most of these 17,000 Chinese workers were brought in from China's southern provinces including Guangdong, and paid around half of what other workers made ($1 a day to the $2–$2.50 paid to other labourers). Their supervisors on the railroad, in addition to paying them so little, forced them to buy supplies and food from the company store,

The cooks built their own type of outdoor ovens in the dirt banks alongside the tracks. Each cook would have the use of a very big iron kettle half full of water hanging over an open fire and into it they would dump cheap unhulled brown rice. Added to the rice were Chinese noodles, bamboo sprouts. dried seaweed, different Chinese seasonings along with salmon and occasionally local chickens cut up into small pieces including the heads, legs, and all. When the cook stirred up the fire the concoction began to boil and the rice would begin to swell until finally the kettle would be nearly full of steaming nearly dry brown rice with the cut up meat all through it. This mixture would be ladled into each worker's rice bowl to be eaten with chopsticks and washed down with many cups of tea. Scurvy was widespread since their diet was lacking in fruit and vegetables which their limited finances could not afford. Most had families to support back in China, to which all available money was sent.

The Chinese were assigned the most dangerous jobs and were given little access to healthcare. Many inflammatory incidents occurred because of accidents for which the Chinese blamed the white foremen. Foremen often bragged that it was possible to move two thousand Chinese at a distance of twenty-five miles and have them at work all within twenty-four hours.

As the demand for labour increased, white workers were reluctant to do the exhausting, hazardous work that was expected from the Chinese. These labourers toiled through back-breaking labour during both frigid winters and blazing hot summers. Many hundreds died from explosions, landslides, accidents and disease. And even though they made major contributions to the construction of the Transcanada Railroad, these thousands of Chinese immigrants have been largely ignored by history.

The last spike on the railroad joining the coasts was famously driven in during the ceremony in Craigellachie, B.C. on November 7, 1885. But little recognition was paid to the Asian workers, who had toiled at the cost of thousands of their lives. No Asians can be seen in the photographs showing the hundreds of people at the ending ceremony.

On the same year that the railroad was completed in 1885, Canada imposed a "head tax" on Chinese immigrants -- initially set at $50 a person. The tax was later raised to $500 -- roughly a year's wages for most -- before Chinese immigration was eventually almost totally banned in 1923 when the Chinese Immigration/Exclusion Act was passed. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald had previously supported some Chinese immigration, saying, “It is simply a question of alternatives: either you must have this labour or you can’t have the railway.” But by 1885, he had changed his tune and argued in Parliament that Chinese immigrants were not adding anything to Canada. ANOTHER SOURCE FOR MORE INFO

www.canadashistory.ca/explore/books/speaking-for-his-compatriots

1885 REWARD FOR COMPLETING THE RR:

HEAD TAX ~ RACISM ~ PREJUDICE ~ HOSTILITIES ~ BANNED IMMIGRATION

The Chinese were tolerated during the construction of the CPR, but the tide of political opinion was about to change as workers laid more track and neared completion of the railway. Even those who survived building the railroad often couldn’t afford to return to China -- nor were they allowed to bring their families to Canada. They were left without jobs in hostile territory. With no means of going back to China when their labour was no longer needed, thousands drifted in near destitution along the completed track. All of them remained nameless in the history of Canada.

After the railroad, emigration from China to "Gold Mountain" continued. Canada, even with its head tax, became the primary destination after the United States enacted its own Chinese Exclusion Act that barred all Chinese immigration to that country from 1882.

White angst and disproportionate fear about an expanding Asian community led to further discrimination from the press, labour unions and politicians. This resulted in violent outbursts -- the worst of which was the Vancouver Race Riots. On September 7, 1907, a meeting at Vancouver's old city hall of the Asiatic Exclusion League, cobbled together by politicians and labour organizers using racism as a political tool to unite the white population, resulted in a mob rampaging through Chinatown and Japantown. This resulted in shattered windows and extensive damage to property. The Chinese community rallied and with the help of the attaché of the Imperial Chinese Legation in London, England, and two consuls from San Francisco and Portland, demanded damages be paid. (China had no diplomatic representation in Canada). It was a small victory for the Chinese Canadian community, but it was followed by more federal measures to prohibit Asian immigration to Canada.

Chinese worked together, through clan associations, the Chinese Benevolent Association and family and village connections, to overcome the obstacle of the head tax, and even the Exclusion Act -- to reunite their families over great distances and through the generations. Many had to send money back to China to support family and some had to pay off debts to their ancestral villages that had sponsored their journey to Canada. Extended families became the norm for some of the "Gold Mountain men." Many relied on unconventional means to ensure their lineage, adopting "paper sons" and other family members and trading identity papers to bring relatives to Canada.

PART II CONTINUED AT:

www.hillmanweb.com/chinese/epic/successes.html

BACK TO CHINESE CONTENTS PAGE

www.hillmanweb.com/chinese

Bill and Sue-On Hillman

Eclectic Studio

www.hillmanweb.comE-MAIL CONTACT:

hillmans@wcgwave.ca