The Choy Family Story

www.hillmanweb.com/soos/choystory.html

by Kenny

Choy and Sue-On Choy Hillman

as told to John Jung

Imprisoned in China, mother and family reunites nine

years later in Canada

Ref: Chinese

Canadian National Council ~ John

Jung

"They had these meetings and they used to

dunk you in a cattle trough and push you from corner to corner to get you

to betray your family or friends, try to get more money out of you."

— daughter Sue-On Choy Hillman.

"Grandpa came here to Winnipeg, did not speak English,

and people made fun of his long pigtail. They gave him a rough time." —

grandson Kenny Choy.

2011: BRANDON, Manitoba — 62 years ago, the fate of

her people on the brink of losing a civil war, Yook Hai Choi knew bad times

would likely befall her family.

Generations of the Choy family were nationalists in China

and had been part of the merchant class. On Oct. 1, 1949 in Beijing, Communist

leader Mao Tse-tung declared China a Communist state in his first address

to the Chinese nation. The advent of Communism in China would crush the

hopes and dreams of millions of Chinese including the Choy family.

The bourgeoisie or merchant class became the prime target

of the new regime. Their new rulers would make examples of the Choys as

they did with many others who were part of that entrepreneur class.

The 42-year-old mother of four would be imprisoned in

1951 after being caught attempting to leave the country at the Hong Kong

border. She had already successfully smuggled her two youngest children,

Kenny and Sue-On, to Hong Kong.

“She was so desperate to leave China,” recounts her son

Kenny, 13 at the time. “So she paid somebody to take her from the old village

to the border between Hong Kong and China. She tried to cross the riverbank

to Hong Kong and she was caught in the bush.”

Her Communist captors jailed her for months. “We had no

idea where she was,” says Kenny. “They always kept members of the family

there because they keep wanting to get more money out of you.”

Although she would be released to her home village of

Dae Gong, Yook Hai Choi and her mother would be persecuted until she was

allowed to leave in 1954 to Hong Kong, her movements were constantly watched

by her Communist monitors for years.

“My mother was eventually allowed to go to Hong Kong but

she went through a lot of persecution as well,” explains her youngest daughter

Sue-On, recounting stories told to her. “They had these meetings and they

used to dunk you in a cattle trough and push you from corner to corner

to get you to betray your family or friends, try to get more money out

of you.”

Sue-On would finally see her mother again when she was

in pre-school. It would take another four years for Yook Hai and her two

children to reunite with her husband, Soo Choy, who was in Canada. By 1958,

it was 11 years after the Chinese Exclusion Act had been repealed in Canada,

which the family had hoped would be the year they would be all reunited

in Canada. “My parents had hopes we would all make it out of China by 1949,

but hopes and expectations are different. It didn’t happen,” says Sue-On.

It was in the small town of Newdale, Manitoba (pop. 265)

where Soo Choy was running a restaurant and hotel that the family would

finally reunite. Sue-On had not seen her father for nine years. For Kenny

it was 11 years and for his wife, it was 10 years since she had last seen

him in China.

Prior to 1947, like other Chinese families, the family

was separated for 24 years because Canada’s 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act

banned most Chinese from coming to Canada. However, their father would

make trips back to China, as allowed under the legislation, in the years

1925, 1928, 1931, 1936, and 1948. He married Yook Hai and would have five

children, one who would die quite young.

An older sister, Sue Sem, would marry in China and only

reunite in Canada years later. Their oldest brother Gene had been in the

United States for many years.

The odyssey of the Choy family began before the 1900s

when their great-grandfather Choy Yet Seed was the first to come to North

America, landing in the state of Washington.

His son Choy Him followed him in 1911 later to Canada

as a merchant and did not pay the $500 Chinese Head Tax. “Grandpa came

as a merchant, working for someone in Vancouver, learned a little English,

then he ended up in Winnipeg to be a houseboy for the Commissioner of Water

Works,” says Sue-On. Prior to that, Choy Him ran a restaurant in Ferrigan,

Saskatchewan.

“Grandpa came here to Winnipeg, did not speak English,

and people made fun of his long pigtail. They gave him a rough time,” says

Kenny. Back in China, though, the country was still ruled by the Ching

Dynasty and the queue or pigtail was a requirement for Chinese to return

to their home village.

“It’s all part of your heritage. You have to have it.

It’s part of your culture,” notes Sue-On. “White people didn’t understand

it was part of the culture just like the aboriginal people wearing braids.

Cutting it off was cutting off part of their life in the old days.”

“You have to have it,” explains Kenny. “The longer the

queue, the more respected they were. My grandfather was a teacher by profession

in China. So, he was well-respected in the home village.”

Choy Him would move to Newdale in the 1930s — a small

town on Highway 16 west of Brandon in south-western Manitoba. He bought

the Fairview Hotel and restaurant.

When their grandfather bought the hotel, it came with

a beer parlour. But a provincial alcohol law only allowed Canadians to

run a beer parlour. Like other Chinese in Canada in the 1930s, Choy Him

could not be a citizen, and had to sell the building. All Chinese in Canada

were considered to have “alien” status under the 1923 Chinese Immigration

Act.

“He had to leave that and sold it, and then bought another

building and called it the Paris Café,” says Sue-On.

In 1923, Choy Him had sent for his son, Choy Soo, and

he would pay his $500 Head Tax to come to Canada. With his father’s help,

he was able to go back and forth to China bringing remittances home, despite

the imposition of Canada’s infamous 1923 Chinese Immigration or Exclusion

Act.

But by 1937, their grandfather Choy Him had decided to

go home to China to take care of the family. He left the restaurant in

Newdale for son Choy Soo to run. Like others in his family, Choy Him would

be stranded once the Communists overran the country by 1949. But he engineered

his own escape from China in 1950.

“He pretended he needed Western medical treatment for

asthma. He first went to Hong Kong for a permit and got it. He came back

to China with a medical permit and in the middle of the night, he used

the permit to get out of China to Hong Kong. Then, he hid in a shack and

built a stone house in Hong Kong in the forest,” says Kenny.

There he would stay until his remaining days and his wife

from China was allowed to join him later when he was ill. Choy Him never

returned to Canada.

Meanwhile, his son had been running the Paris Café

in Newdale for more than 20 years by 1958. Once his family joined him,

Choy Soo and his family would run the restaurant for another 14 years before

moving to Brandon in 1972.

His children say their father never encountered the racism

that grandfather Choy Him experienced from 1911 to the 1930s.

“He had good friends, he ran a good business. He came

in when he was 13. He spoke perfect English,” notes Kenny, adding his father

was the first Chinese-Canadian Master in the Masonic Lodge in Manitoba.”

Dad was just one of those guys who got along with everyone,” adds Sue-On.

Since 1919, a provincial law forbade the hiring of white

women in Chinese restaurants but that kind of discriminatory law had long

been rescinded by the time the family came to Newdale in the 1950s to help

run the Paris Café. “Grandfather and Dad ran it. When Dad ran it,

he was able to hire waitresses. Even after we came, we worked in the restaurant

with the waitresses,” notes Sue-On.

Even in her grandfather’s time, the men would run the

restaurant, especially if there was a father and son. Sue-On believes the

provincial law was much less enforced in small towns like Newdale than

in Winnipeg or other cities during the first part of the 1900s.

Kenny says when he came to Newdale in 1959 as a 21-year-old,

he didn’t experience any discrimination. “When I came here, I was able

to communicate with people, like my father.”

Small towns were a different experience for some Chinese

families in the 1950s, says Sue-On. “I fought with the boys. They did call

you names, but they didn’t really understand so I beat the hell out of

them and we became friends. It depends on who came before you.”

For the Choys, southern Manitoba has a long history of

Chinese settlement with most families coming from the Taishan region of

southern China.

“There has been the Choys, the Lees in Minnedosa and Neepawa,

a Yee in Winnipeg, the Wongs and Yuens in Brandon. For our father to come

to Newdale, lots of our fellow immigrants came to this area because of

him,” notes Kenny.

After moving to Brandon in 1972, Kenny and Sue-On’s father,

Choy Soo, decided to open Soo’s Chop Suey House.

Choy Soo and Yook Hai finally retired in 1982. Father

Choy Soo would subsequently pass away in 1983 at 76 while their mother,

Yook Chai, would pass on in 2010 at the age of 101. She would be survived

by four children, 11 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren.

Soo’s Chop Suey House would be run by Kenny and his wife

Rebecca for 10 years until 1992. Then Sue-On and her husband Bill took

it on until it officially closed in 2002. Soo’s Chop Suey House was the

longest-running Chinese restaurant in Brandon for 30 years and owned by

the same family during that time.

West on Highway 16 on the Yellowhead, Chinese cafés

and restaurants dot the landscape on this major highway in towns like Newdale,

Gladstone, Plumas, Neepawa, Minnedosa, Newdale, and Shoal Lake. “In earlier

times, these people all came from our village, including Ethelburg, Saskatchewan,”

notes Sue-On.

“It’s because of one man and they sponsored another one

and would bring them. In another town, another family would come. I know

there were a lot of Choys in Neepawa, Newdale, Gladstone, Plumas, and in

Shoal Lake, there’s one. Sometimes there’s a descendant on the wife’s side

or a connection from the past.” Today, some of the restaurants are run

by Chinese families from China, but many of them are Korean-owned now.

In Brandon, the Chinese community has expanded in recent

years as employers like Maple Leaf Foods hired new immigrants from China,

Mauritius, and the Ukraine to fill vacancies in their plant. The city’s

Chinese community has increased dramatically, composed of those families

who came from the past — the Toishanese, and those who have come recently

from northern China, most whom speak Mandarin.

Since 1991, Kenny had been thinking about some kind of

memorial to dedicate to the Chinese ancestors who once settled the community.

Many of them are buried in the Brandon Municipal Cemetery on 18th Street

South, including his mother.

“Some of the graves have been about 100 years old. A 23-year-old

young man came here, must have got a disease, then died. Nobody ever has

put incense and flowers, so we started that again. Many of our relatives

are buried there,” notes Kenny.

Every year during Ching Ming (Qing Ming in China) time

from April to June, the Chinese community would go to the cemetery and

honour those who had passed with incense, flowers, and food offerings.

Ching Ming or Clear Brightness Festival is a traditional Chinese festival

observed to pay tribute to ancestors by mourning the dead and visiting

their graves. It’s also a chance to attend and clean up the graves of relatives.

It is still observed throughout Chinese communities in Canada and in other

Asian countries.

As Ching Ming observances grew with more and more Chinese

coming to the Brandon cemetery, there was a need to bring people together

after private observances at the cemetery. Each year, a banquet is now

held at a local restaurant for all Chinese in Brandon during Ching Ming

time.

For Kenny, however, more was needed to honour the history

of the people who were part of the Chinese community in Brandon. “We needed

something to remind the new immigrants and to remind the young Chinese

people that are coming up in the next generation to remember what kind

of sacrifices were made by their ancestors. It’s because of their ancestors

they had the opportunity to come,” notes Kenny.

Sue-On

Sue-On, who teaches at Brandon University, says there

is no curriculum or resource material in Manitoba on the Chinese-Canadian

experience or history of the community in high school. Not one of her students

knew anything about the history of Chinese in Canada. “They knew nothing

about our history. They had no idea about the Head Tax,” she says.

Kenny’s idea would become a practical plan to build the

first Head Tax Monument in Canada. And the formation of the Westman Chinese

Association in Manitoba in 2007.

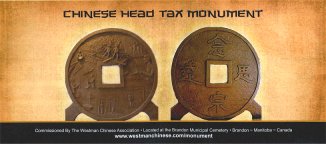

The end result was an 8-foot-diameter bronze Chinese coin,

depicting different eras of the Chinese-Canadian settlement and history

in Canada and in Brandon. It would be unveiled officially at Brandon Municipal

Cemetery on June 26, 2011, attracting hundreds of local residents from

the area and many more from outside since.

Noted sculptor Peter Sawatzky would be commissioned to

produce the coin, which has a marble granite base footing. “The reason

we had marble granite was that the Chinese worked hard and established

themselves as contributing citizens. Marble probably came from China, but

it represents a black period in our history,” says Kenny.

Mr. Sawatzky thought the concept of a coin would be appropriate

because during the time that the Chinese were coming to Canada, the Ching

Dynasty ruled China and the bronze coin was used as currency during that

period. “Everything with this monument has a meaning. It’s a symbol. The

reason for the coin is the money when the Chinese first came to Canada.

The reason we came here was to make money. And to help our families in

China,” says Kenny.

There are also etchings on the coin, depicting different

periods of time for Chinese Canadians — the gold mine era, building the

Canadian Pacific Railway, the Head Tax years, the Exclusion era, the repeal

of the Chinese Exclusion Act, and later the advent of technology as Chinese

become more successful and are allowed to pursue professional work in Canada.

A laundry and Soo’s restaurant are also on the coin representing

the only ways early Chinese could earn a living in Canada, as is an immigration

officer collecting the Head Tax.

The coin was struck in Montana and was shipped up to Brandon,

taking a year to build. Including volunteer time, Kenny says the cost of

the project amounted to about $160,000. The Choy family donated money,

as did local people like the Rotary Club and other Chinese-Canadian families

affected by the Head Tax. Kenny was also able to receive federal grant

funds under the Community Historical Recognition Program. The city of Brandon

donated the land and the provincial government helped in ensuring the project

was completed. The calligraphy in Chinese was done by a new immigrant.

It means: “In remembrance of our ancestors.”

The Chinese Head Tax Monument is pointed to the northeast,

towards China, once the homeland of all the Chinese people who came to

Canada. There is a place for visitors to put incense and offerings.

“It’s not only for Chinese people but also for Canadians,

and a point of interest for tourists. They’re learning about history. There‘s

nothing like this in Canada. It‘s a lasting monument,” notes Sue-On.

“People don’t know about the Head Tax. Lots of people

know about it now,” observes Kenny. “I didn’t want a headstone, I wanted

a piece of art that would last.”

For the Choy family, their history in rural Manitoba is

part of a long lineage of Chinese-Canadian settlement in Western Canada

that only many residents and other Canadians are beginning to understand

and appreciate. An 8 ft. Chinese coin will preserve that collective legacy

for generations to come.