8 Things You Need To Know About The Battle Of

Britain

Imperial

War Museums

The Battle of Britain was a major air campaign fought

over southern England in the summer and autumn of 1940. Here are 8 things

you need to know about one of Britain’s most important victories of the

Second World War.

1. Hitler wanted to invade

Britain in 1940

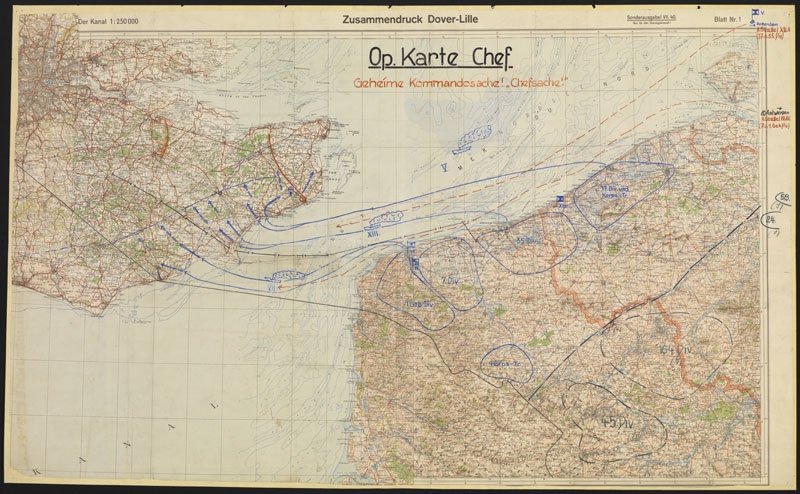

One of many German maps of the planned invasion of

Britain.

Adolf Hitler had expected the British

to seek a peace settlement after Germany’s defeat of France in June 1940,

but Britain was determined to fight on. Hitler explored military options

that would bring the war to a quick end and ordered his armed forces to

prepare for an invasion of Britain – codenamed Operation ‘Sealion’. But

for the invasion to have any chance of success, the Germans needed to first

secure control of the skies over southern England and remove the threat

posed by the Royal Air Force (RAF). A sustained air assault on Britain

would achieve the decisive victory needed to make ‘Sealion’ a possibility

– or so the Germans thought.

2. The Battle of Brtiain

saw the RAF take on the German Air Force

Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief Hermann Göring with

members of the German armed forces, 1940.

The Battle of Britain was ultimately

a test of strength between the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) and the RAF.

The RAF had become an independent branch of the British armed forces in

1918. Although it developed slowly in the years following the First World

War, it went through a period of rapid expansion in the latter half of

the 1930s – largely in response to the growing threat from Nazi Germany.

In July 1936, RAF Fighter Command was established under the leadership

of Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding. Germany had been banned from having an

air force after the First World War, but the Luftwaffe was re-established

by the Nazi government and by 1940 it was the largest and most formidable

air force in the world. It had suffered heavy losses in the Battle of France,

but by August the three air fleets (Luftflotten) that would carry out the

assault on Britain were at full readiness. The RAF met this challenge with

some of the best fighter aircraft in the world – the Hawker Hurricane and

the Supermarine Spitfire.

3. The British had developed

a highly effective air defence network

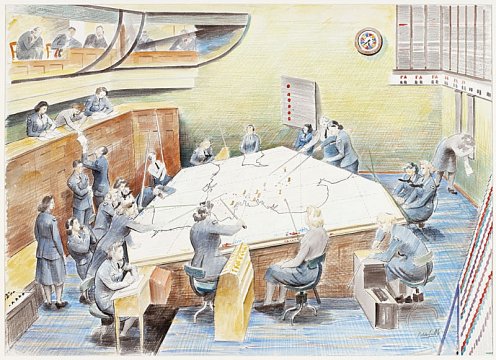

Group Headquarters, Uxbridge: radiolocation plotters,

by Roland Vivian Pitchforth.

The British developed an air defence

network that would give them a critical advantage in the Battle of Britain.

The Dowding System – named for Fighter Command’s Commander-in-Chief Sir

Hugh Dowding – brought together technology, ground defences and fighter

aircraft into a unified system of defence. The RAF organised the defence

of Britain into four geographical areas, called ‘Groups’, which were further

divided into sectors. The main fighter airfield in each sector – the ‘Sector

Station’ – was equipped with an operations room from which the fighters

were directed into combat. Radar gave early warning of Luftwaffe raids,

which were also tracked by the Observer Corps. Information on incoming

raids was passed to the Filter Room at Fighter Command Headquarters at

Bentley Priory. Once the direction of the raid was clearly established,

the information was sent to the relevant Group’s headquarters. From there

it was sent to the Sector Stations, which would ‘scramble’ fighters into

action. The Sector Stations received updated information as it became available

and further directed airborne fighters by radio. The operations rooms also

directed other elements of the defence network, including anti-aircraft

guns, searchlights and barrage balloons. The Dowding System could process

huge amounts of information in a short period of time. It allowed Fighter

Command to manage its valuable – and relatively limited – resources, making

sure they were not wasted.

4. There were several

phases to the Battle of Britain

Contrails left by British and German aircraft after

a dogfight during the Battle of Britain, September 1940.

The Battle of Britain took place between

July and October 1940. The Germans began by attacking coastal targets and

British shipping operating in the English Channel. They launched their

main offensive on 13 August. Attacks moved inland, concentrating on airfields

and communications centres. Fighter Command offered stiff resistance, despite

coming under enormous pressure. During the last week of August and the

first week of September, in what would be the critical phase of the battle,

the Germans intensified their efforts to destroy Fighter Command. Airfields,

particularly those in the south-east, were significantly damaged but most

remained operational. On 31 August, Fighter Command suffered its worst

day of the entire battle. But the Luftwaffe was overestimating the damage

it was inflicting and wrongly came to the conclusion that the RAF was on

its last legs. Fighter Command was bruised but not broken. On 7 September,

the Germans shifted the weight of their attacks away from RAF targets and

onto London. This would be an error of critical importance. The raids had

devastating effects on London’s residents, but they also gave Britain’s

defences time to recover. On 15 September Fighter Command repelled another

massive Luftwaffe assault, inflicting severe losses that were becoming

increasingly unsustainable for the Germans. Although fighting would continue

for several more weeks, it had become clear that the Luftwaffe had failed

to secure the air superiority needed for invasion. Hitler indefinitely

postponed Operation ‘Sealion’.

5. Not all of the pilots

were British

Czech pilots of No. 310 Squadron at RAF Duxford in

September 1940.

Nearly 3,000 men of the RAF took part

in the Battle of Britain – those who Winston Churchill called ‘The Few’.

While most of the pilots were British, Fighter Command was an international

force. Men came from all over the Commonwealth and occupied Europe – from

New Zealand, Australia, Canada, South Africa, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe),

Belgium, France, Poland and Czechoslovakia. There were even some pilots

from the neutral United States and Ireland. Two of the four Group Commanders,

11 Group’s Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park and 10 Group’s Air Vice-Marshal

Sir Quintin Brand, came from New Zealand and South Africa respectively.

The War Cabinet created two Polish fighter squadrons, Nos. 302 and 303,

in the summer of 1940. These were followed by other national units, including

two Czech fighter squadrons. Many of the RAF’s aces were men from the Commonwealth

and the highest scoring pilot of the Battle was Josef Frantisek, a Czech

pilot flying with No. 303 (Polish) Fighter Squadron. No. 303 entered battle

on 31 August, at the peak of the Battle of Britain, but quickly became

Fighter Command’s highest claiming squadron with 126 kills.

6. 'The Few' were supported

by many

Anti-Aircraft Defences, 1940, by C R W Nevinson.

Many people in addition to Churchill’s

‘Few’ worked to defend Britain. Ground crew – including riggers, fitters,

armourers, and repair and maintenance engineers – looked after the aircraft.

Factory workers helped keep aircraft production up. The Observer Corps

tracked incoming raids – its tens of thousands of volunteers ensured that

the 1,000 observation posts were continuously manned. Anti-aircraft gunners,

searchlight operators and barrage balloon crews all played vital roles

in Britain’s defence. Members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF)

served as radar operators and worked as plotters, tracking raids in the

group and sector operations rooms. The Local Defence Volunteers (later

the Home Guard) had been set up in May 1940 as a ‘last line of defence’

against German invasion. By July, nearly 1.5 million men had enrolled.

7. All of the RAF helped

defend Britain

Whitley bomber crews attend a briefing before a raid

over Germany, 29 August 1940.

The RAF was organised into different

‘Commands’ based on function or role, including Fighter, Bomber and Coastal

Commands. While victory in the Battle of Britain was decisively gained

by Fighter Command, defence was carried out by the whole of the Royal Air

Force. Britain’s most senior military personnel understood the importance

of the bomber in air defence. They wrote on 25 May: ‘We cannot resist invasion

by fighter aircraft alone. An air striking force is necessary not only

to meet the sea-borne expedition, but also to bring direct pressure to

bear upon Germany by attacking objectives in that country’. In other words,

RAF Bomber Command would attack German industry, carry out raids on ports

where Germany was assembling its invasion fleet, and reduce the threat

posed by the Luftwaffe by targeting airfields and aircraft production.

RAF Coastal Command also had an important role. It carried out anti-invasion

patrols, provided vital intelligence on German positions along the European

coast and occasionally bombed German shipping and industrial targets.

8. The Battle of Britain

was a defensive victory for Britain

Spitfire pilots pose beside the wreckage of a Junkers

Ju 87 Stuka, 1940.

During the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe

was dealt an almost lethal blow from which it never fully recovered. Although

Fighter Command suffered heavy losses and was often outnumbered during

actual engagements, the British outproduced the Germans and maintained

a level of aircraft production that helped them withstand their losses.

The Luftwaffe, with its lack of heavy bombers and failure to fully identify

critically important targets, never inflicted strategically significant

damage. It suffered from constant supply problems, largely as a result

of underachievement in aircraft production. Germany’s failure to defeat

the RAF and secure control of the skies over southern England made invasion

all but impossible. British victory in the Battle of Britain was decisive,

but ultimately defensive in nature – in avoiding defeat, Britain secured

one of its most significant victories of the Second World War. It was able

to stay in the war and lived to fight another day. Victory in the Battle

of Britain did not win the war, but it made winning a possibility in the

longer term. Four years later, the Allies would launch their invasion of

Nazi-occupied Europe – Operation ‘Overlord’ – from British shores, which

would prove decisive in ultimately bringing the war against Germany to

an end.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

.

.