094 of

150: Al Mackay - Wireless Air Gunner - Oral History

Allan D. MacKay, Fillmore Saskatchewan (AC2, LAC,

Sgt., Flight Sgt., WO2, WO1, PO, FO).

Enlisted, Brandon Manitoba October 1940 as Aircrew.

Sworn in July 14/1941 – Vancouver B.C.

Was one of the first Army Trainees at (Artillery School)

A4 Brandon

At that

time, 21-year-olds (army enlistees) were given one month training. So I

was a "Grenadier" for a month, but had already decided on the Air Force.

No propaganda had any influence on my decision to join the RCAF – it just

seemed the right time and of course, everyone wanted to be a pilot. But

at that time they had too many pilots so my next choice was Wireless

Air Gunner.

At that

time, 21-year-olds (army enlistees) were given one month training. So I

was a "Grenadier" for a month, but had already decided on the Air Force.

No propaganda had any influence on my decision to join the RCAF – it just

seemed the right time and of course, everyone wanted to be a pilot. But

at that time they had too many pilots so my next choice was Wireless

Air Gunner.

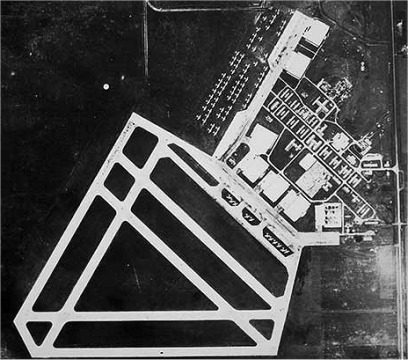

For training, I arrived in Brandon on July 17, 1941 and

was posted to the Brandon Manning Depot. When we arrived from Vancouver,

the Manning Depot was full so us ERKS (ground crew) were housed on the

3rd Floor of #33 Tenth Street in Brandon – hot as hell! One week later

we got into No. 2 Manning Deport at 10th and Victoria Avenue. We were there

six weeks – mostly Guard Duty. But seeing as how I had had experience in

marching, I was put on the drill team - "Big Deal!"

The food was good and the cow barn smell was mostly gone

(prior to being No. Manning Depot, the Wheat City Arena was home to agricultural

events which offered housing for animals in attached barns). Had a great

bunch of mates – no problems. We left for Claresholm, Alberta for six weeks

of General Duties -- then in October 1941 we went to Wireless School in

Winnipeg, Manitoba. It was at the old Normal School in "Tuxedo" (suburb

of Wpg). We had to attain 35 words per minute in Morse Code, learn about

radio receivers and transmitters, but there was no radar training yet.

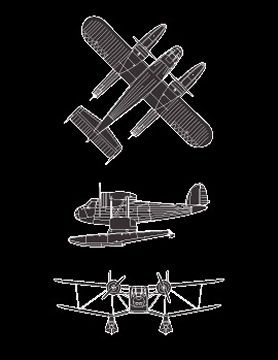

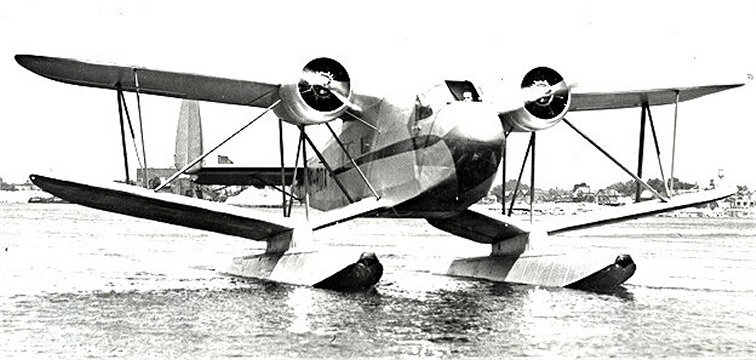

We had some radio training in Tiger Moth aircraft and some in the Norseman-

mostly over Lake Winnipeg and Lake Manitoba.

We had very good instructors. One was Lloyd Lee from around

Waskada, Manitoba and he was a genius in radio. The only real thrill other

than 'Girls' was a Virden pilot who loved to come down on the lake on the

ice and bump the front wheel on ripples in the ice – it scared hell out

of us.

Graduation from wireless was no big deal. We just received

our "Spark’s Badge" then were posted to Bombing and Gunnery School at McDonald,

Manitoba. Training there was in the Fairey Battle -- some had been in Dunkirk

and looked like it. The meals were always good, probably because I was

such a fine fellow. I only had one bad experience in Winnipeg – a fine

young man shot himself in a vestibule on Portage Avenue – it was very sad.

Our Wings Parade in McDonald was very well put on and

on of course, we were then Sergeants.

I was posted to Ferry Command and given one month leave.

While on leave my posting was cancelled as no planes were available. So

I was posted to Gaspe, Quebec for Ground Duty for three months. That consisted

of drinking beer – Black Horse Quarts. I was finally posted to a refresher

course in gunnery at #6 B&G at Mountain View, Ontario outside of Bellville.

At Gaspe I flew one operational flight in a Canso as Spare Wireless Operator.

Being such as brilliant gunner, I was presented with the silver wings as

first in my class. I was also supposed to be commissioned as an officer,

but a 48 hour leave in Toronto blew that -- enough said.

Of the 20 or so postings, I was the only one posted overseas

but I had requested that. I arrived in Halifax on January 1, 1943. I got

engaged to the girl I had met in Brandon back in July 1941 – Grace Goldstone

-- and I left from Brandon for Halifax. It was forty below the night I

left. Halifax was not the best station in the world, but then people were

coming and going every day. My brother was in the air force as a motor

mechanic instructor and was at Moncton, New Brunswick which I never knew

at the time.

Our trip overseas was on the Empress of Scotland which

was a good boat. We had good quarters and I was able to find my girlfriend’s

brother who was on the same boat. I had never met him but somehow I ran

into him. We went across in a convoy. We were required to man the Orlikon

Guns at certain hours. I think it took five days to reach Greenock, Scotland

and then we took a train to Bournemouth. We were only there for a short

time. I was then posted up to Chester in "Cheshire" for Radar Training.

We used Botha aircraft. Now I want to tell you it was not all work at Chester.

There was a Lever Brothers Soap Factory beside the station and it employed

about 200 ladies and this was war? Also we were close to Liverpool.

Now I want to tell you that my friend from Roblin, Manitoba,

Harold Keast – now deceased -- decided after a night in the pub to go to

Blackpool, a resort north of Liverpool.

In the morning before catching the double-decker bus

to Blackpool, we thought we should have a half dozen pints of Mild &

Bitter, so about half way to Blackpool I needed a bathroom as that Mild

& Bitter was a bit heavy in the bladder. We had a chat with the lady

ticket-clipper and told her about my problem. She never batted and eye

and said "Canada - do no worry, up ahead is a small shack across the road

and I’ll stop the bus and you can nip across behind said shack." Which

I did and thanked her so much.

After Chester, we were sent to a holding unit and then

to an Operational Training Unit at Cranwell in Lincolnshire, home of the

Royal Air Force. There we were put into crews and were to go to Coastal

Command at Cranwell. It was a very nice station, only thing was it was

RAF so we did a lot of saluting. As we were to fly Wellington (Wimpy) bombers,

that’s what we trained on and all being new we immediately got quite lost

on our first training flight. But we managed to get back a bit late.

I

had to take a radar flight in an Anson and as we went down the runway,

the pilot asked me to do something and I reached over my head and hit an

engine switch and shut down one engine so the pilot did a ground loop and

said I did it. You crank it. When we finished the course, were posted to

407 – the Canadian Demon Squadron. We were stationed in Devon. The night

we arrived, a Wimpy with the new engines was being test flown on one engine

and crashed and burned at the end of the runway. All on board were killed.

Our first eight hour patrol, looking for U-Boats, was in July 1943. We

flew about 24 U-Boat patrols until January 1944 when they posted us to

Limevary North Ireland for maneuvers with the Fleet.

I

had to take a radar flight in an Anson and as we went down the runway,

the pilot asked me to do something and I reached over my head and hit an

engine switch and shut down one engine so the pilot did a ground loop and

said I did it. You crank it. When we finished the course, were posted to

407 – the Canadian Demon Squadron. We were stationed in Devon. The night

we arrived, a Wimpy with the new engines was being test flown on one engine

and crashed and burned at the end of the runway. All on board were killed.

Our first eight hour patrol, looking for U-Boats, was in July 1943. We

flew about 24 U-Boat patrols until January 1944 when they posted us to

Limevary North Ireland for maneuvers with the Fleet.

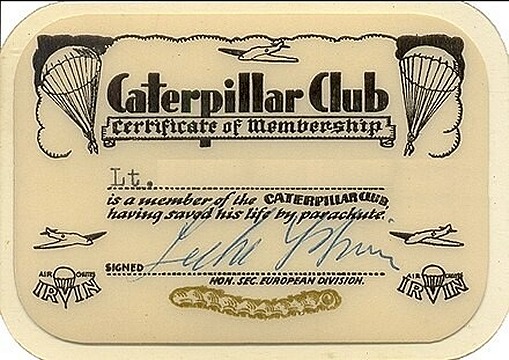

I must mention that on Remembrance Day in 1943 we had

been out about nine hours and when we were about 100 miles from the base,

we received a message that the base was fogged-in so we diverted to Leaming.

But it was also fogged-in so as a last resort I called the Search Light

Station for guidance to an open airport. They guided us right out over

the ocean and shut off lights. We were low on fuel and after 10 ½

hours in the air, one engine quit. The pilot took us up to 6000 feet and

told us to bail out. We had a crew of seven that night, so me being the

No. 1 WAG, I was third last

to leave. The tail gunner didn’t want to jump so I went back turned the

turret manually and told him to count 10 and pull the ripcord. I assisted

him out. Then I went back up to the front and bailed out myself. That’s

where that "O" ring came from. I guess it slipped back on my wrist when

I pulled it. I looked up and didn’t think it had opened but the wind picked

up and I could see lovely silk above.

The fog base was approximately 50 feet . I came through the

fog at 50 feet heading for trees. I had heard someone say if you want to

steer a parachute, pull on shroud lines and I didn’t want approximately

50 miles per hour speed. I landed flat on my ass in a wet plowed field

and knew I was dead. But I wasn’t – but it was 2:30 in the morning. It

was a small field with a ditch full of water all around. I buried the parachute

as instructed and found the best way out of the field. I didn’t know where

we were, so I walked about a mile and found the village of Kanoctted. I

knocked on a door and was greeted by a man and shotgun. He thought I was

the German Air Force. It took some time to convince him. The actual Village

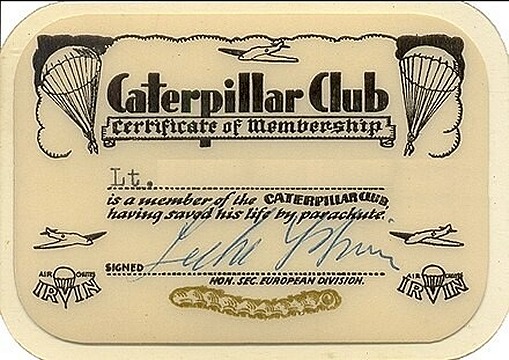

was Bromley in Kent. So I became a member of the Caterpillar Club (reserved

for air foce personnel who used a parachute to escape a doomed aircraft).

Another small thrill was on takeoff in October 1943 with

a load of depth charges. We lost an engine as we got off the ground and

had to jettison the charges in the bay. We landed on one engine. Later

on, we were turning over and I was in the tail turret having a smoke when

I saw trees going by! We had been given height in meters instead of feet

and lost hydraulics so we had no landing gear and no flaps, no brake and

bugger all but we had a good pilot. He had many hours instructing at Claresholm

and came back to base to land on grass by the runway. No one was even scratched.

We bombed four German destroyers around New Years. Forty-four

aircraft carried bombs that night. We also lit up a British destroyer one

night – we sure got the hell out of there in a hurry.

Half of Squadron 407 was transferred to Limavady, Northern

Ireland for training with the U.S. Navy. That ended in March 1944 and we

were given a chance to go to a different squadron or consider volunteering

for duty in the Pacific. I was posted to Warrington repatriation and ended

up in the hospital with acute sinusitis and had to have sinus surgery.

That meant having a hollow needle driven up the nose to drain the sinus.

I had this done four times at Warrington and once more at the Army Hospital

outside of London. It was no fun.

In the meantime, the rest of the crew except the pilot

left for home. After the hospital I had a chance to rejoin 407 but with

a different crew. A buddy of mine wanted me to join his crew which I almost

did but decided I would come home. My choice was lucky for me but sad for

the new crew as they were shot down in the channel on their first trip.

All were killed.

I came home in May 1944 and got married in June 1944.

I was posted to Pat (Patricia) Bay and rejoined my old crew. We flew out

of Pat Bay on sub patrol for one year (July 1944 to July 1945. I was commissioned

in December 1944 to Pilot Officer. Our daughter Judith Anne was born on

April 21 1945. In July 1945 I flew to Vancouver in a DC3 Dakota and was

discharged exactly four years to the day (July 17) that I had located to

the Manning Depot in Brandon.

Some of the best memories of England and Scotland were

the dances at Hammersmith Palace or Convent Gardens and also in Edin Bergen

at the Palais there. I also enjoyed a visit to the Soho District of London

– it was August and I got very drunk and woke up on the Flying Scotsman

just outside of Edenborough. Harold thought it quite funny but we loved

laying in the heather. A lady who owned a pub always left a bottle of Johnny

Walker Scotch for me.

I was promoted to Flying Officer just before discharge.

I could have gone to the Queen Charlotte Islands as Commanding Officer

but took my discharge. The planes I flew in were the Tiger Moth, Norseman,

Anson, Fairey Battle, Bolingbroke, Catalina, Botha, Wellington Wimpy and

Ventura. My last flight was in a Dakota DC3.

Al passed away in 2013 at the age of 92. His wife Grace

predeceased in 2002.

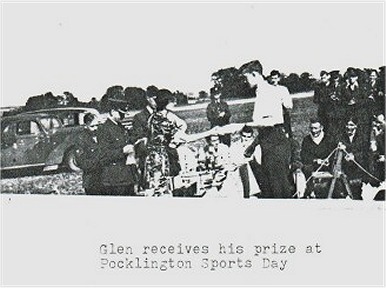

We

had a big field day at Pocklington and the rivalry between RCAF & RAF

was pretty intense. I think we piled up more points, it's on record in

Wings Abroad but that's not the story. I was the first to go up for my

prize being presented by the wife of the Group AOC, an Air Marshal, she

was a real Brit. Now I was just a raw kid from a small town in Saskatchewan

and no one had ever told me that a gentleman waits for a lady to offer

her hand before shaking. I had never before been awarded anything without

a handshake so I took my prize in the left hand and held out my right.

She paused. I held it out there. Then she took it. I learned a little of

England and she learned a little of Canada that day. Probably did us both

good.

We

had a big field day at Pocklington and the rivalry between RCAF & RAF

was pretty intense. I think we piled up more points, it's on record in

Wings Abroad but that's not the story. I was the first to go up for my

prize being presented by the wife of the Group AOC, an Air Marshal, she

was a real Brit. Now I was just a raw kid from a small town in Saskatchewan

and no one had ever told me that a gentleman waits for a lady to offer

her hand before shaking. I had never before been awarded anything without

a handshake so I took my prize in the left hand and held out my right.

She paused. I held it out there. Then she took it. I learned a little of

England and she learned a little of Canada that day. Probably did us both

good.

.

.

At that

time, 21-year-olds (army enlistees) were given one month training. So I

was a "Grenadier" for a month, but had already decided on the Air Force.

No propaganda had any influence on my decision to join the RCAF – it just

seemed the right time and of course, everyone wanted to be a pilot. But

at that time they had too many pilots so my next choice was Wireless

Air Gunner.

At that

time, 21-year-olds (army enlistees) were given one month training. So I

was a "Grenadier" for a month, but had already decided on the Air Force.

No propaganda had any influence on my decision to join the RCAF – it just

seemed the right time and of course, everyone wanted to be a pilot. But

at that time they had too many pilots so my next choice was Wireless

Air Gunner.

I

had to take a radar flight in an Anson and as we went down the runway,

the pilot asked me to do something and I reached over my head and hit an

engine switch and shut down one engine so the pilot did a ground loop and

said I did it. You crank it. When we finished the course, were posted to

407 – the Canadian Demon Squadron. We were stationed in Devon. The night

we arrived, a Wimpy with the new engines was being test flown on one engine

and crashed and burned at the end of the runway. All on board were killed.

Our first eight hour patrol, looking for U-Boats, was in July 1943. We

flew about 24 U-Boat patrols until January 1944 when they posted us to

Limevary North Ireland for maneuvers with the Fleet.

I

had to take a radar flight in an Anson and as we went down the runway,

the pilot asked me to do something and I reached over my head and hit an

engine switch and shut down one engine so the pilot did a ground loop and

said I did it. You crank it. When we finished the course, were posted to

407 – the Canadian Demon Squadron. We were stationed in Devon. The night

we arrived, a Wimpy with the new engines was being test flown on one engine

and crashed and burned at the end of the runway. All on board were killed.

Our first eight hour patrol, looking for U-Boats, was in July 1943. We

flew about 24 U-Boat patrols until January 1944 when they posted us to

Limevary North Ireland for maneuvers with the Fleet.

.

.