112

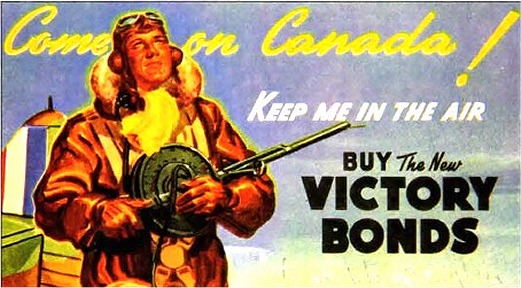

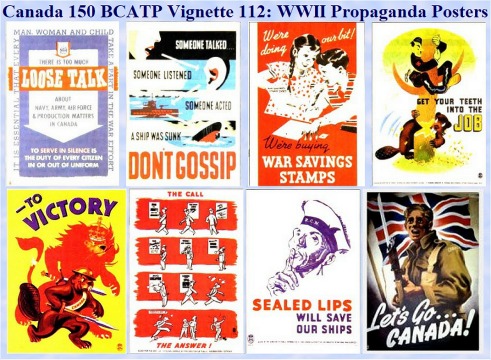

of 150: The Poster as Propaganda

LEGION Magazine - NOVEMBER 1988

Persuasion

by Dave Mcintosh

Posted in military canteens and other public places in Winnipeg

in 1942 was the following message: "People who invite you to parties do

not expect as payment the details of our equipment, movements, orders.

If they do report them, and we will throw a party for them. Military information

is one subject where it is not more blessed to give than to receive."

Such warnings were as familiar as ration books to those

who lived through WW II, and though the advice in Winnipeg was a little

on the wordy side, you couldn't miss the point. In that respect, it was

typical of that venerably ubiquitous genre, the war poster.

The first Canadian military posters, or broadsides, were

used for recruiting in the 1885 Riel Rebellion. In WW I, posters were produced

either officially or on its own initiative by the Canadian advertising

industry for the Patriotic Fund, Red Cross, YMCA, Knights of Columbus,

Salvation Army and other groups. Later, a war poster service was established

In WW II, the production and distribution of posters was more haphazard,

at least in the early stages, and surprisingly little information survives

about the artists, who commissioned their work and how the posters were

issued.

No government department took control until mid-1940,

when the office of the Director of Public Information was established under

the ministry of National War Services. It was succeeded by the Wartime

Information Board, which acted for the departments of National Defence

and Munitions and Supply, National Salvage Office, Canadian Food Board,

and other agencies. The National Film Board became responsible for design

and distribution.

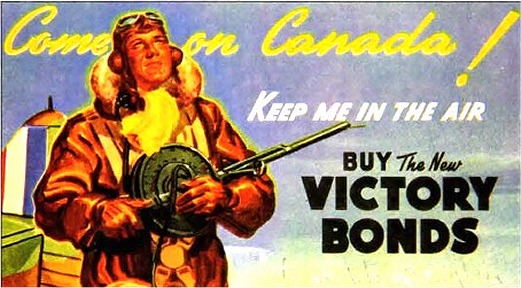

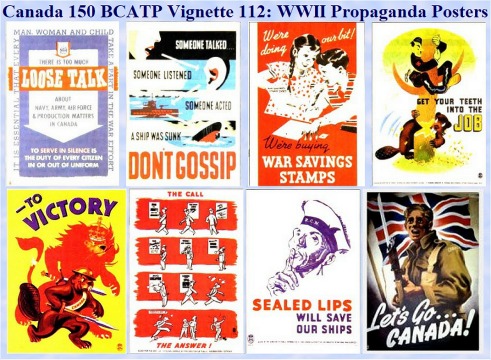

In 1940, the National War Finance Board launched campaigns

for victory bonds, stamps and certificates. There were national and local

contests for poster designs. ln 1941, A.J. Casson of the Group of Seven

artists beat out 110 rivals in a V-bond poster contest. Posters contributed

enormously to bond drives. They appeared not only in newspapers, magazines

and other literature, but on billboards and lamp posts and in factories,

offices and street cars. It would have been difficult to avoid them. Those

shown here were small enough to insert in letters and cigarette cartons.

Some appeared on blotters and letterheads.

The poster generally considered to have been most effective

was "Let's Go, Canada," showing a soldier charging with fixed bayonet.

Despite that, Canada's wartime posters were relatively gentle. Directed

not at the enemy but at the home front and encouragement of Canadian servicemen

overseas, they were intended as a cheerful spur.

The first WW I poster, for the Naval Service of Canada,

shows the cruiser Niobe and advertises "great attractions for men and boys."

You can see that one, and about 4,000 others, at the Canadian War Museum

in Ottawa. The person in charge of the collection is F. Fagan at 1(613)

992-7946.

With thanks to Beatrice M. Turner of London,

Ont.

To see a couple of interesting articles and a large number

of WWII posters issued by the Government of Canada to sell Victory Bonds

and distribute the war message via propaganda as assembled by Bill Hillman,

please go to the CATP Museum web page at:

http://www.hillmanweb.com/war/2017/1707.html

Click for full-size

113

of 150: A World War II Memory - Sam and Glen Merrifield Part 10

Glen and Sam Merrifield along with their friend Stoney

Stonehouse, continue to spin tales of the life as Royal Canadian Air Force

ground crew working with 405 Squadron during World War II. They find themselves

continuing their war from St. Eval, an isolated RAF station in the southwest

of England.

Stoney (friend Russ Stonehouse) says "Remember the North

Africa Campaign and how 405 was taken from Bomber Command to replace the

RAF Liberator Squadron at Beaulieu to do Coastal Command work in support

of Montgomery's" push in North Africa. How we had to chase ponies off the

runways to get aircraft in the air. No hangars to do major overhaul etc..

Then the night the Canadian Army Ambulance rolled in from Poole (outside

Bournemouth) rifled two barrels of beer from the Sgt's Mess and took off.

About one of the slickest commando raids of the war. Naturally all Canadians

from the squadron were accused of the operation. Also how the pubs in the

village of Brockenhurst (near Beaulieu) would not allow us into the lounge

of the pubs because all we had to wear was battle dress. Our dress blues

in most cases were still at Topcliffe and the billeting at Beaulieu was

not all the best and we just did not worry about No. 1 Blues. At Beaulieu

we were always in dutch with the Service Police because our I. D. Cards

had our Squadron number etc. blacked out as the squadron was on special

duty and we were not to identify our squadron as such. (Real top secret

but Lord Haw-Haw knew where we were) Oh how we abused that little privilege

around Bournemouth.

During our stay in Beaulieu I had my leave over New Years

which was spent in Edinburgh for the third "Hogmenay" in a row in Scotland.

My dancing partner on that leave had to be in Dalkeith, eight miles away,

for a family get together New Years morning and we wished to welcome in

the New Year at the large Palais de Dance in the city. The problem was

the scarcity of taxis, and the cost, and the bus system which stopped at

11 p.m. You guessed it ... we walked. Rather than walk back alone I called

in to the local police station and they put me up in a cell I caught the

bus back to the city in the morning.

Our Halifaxes had depth charges and an added gas tank

in the bomb bays for these coastal command stooges but often when extra

penetration and time in the air was required we used St Eval as a forward

base. The following 1981 anecdote entitled "St Eval Cough" follows:

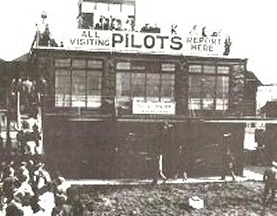

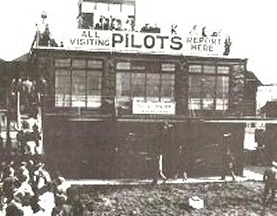

St Eval Maps and Tower

St Eval was a Coastal Command Station on the Bristol Channel.

While we were doing our Coastal Command assignment from Beaulieu we used

St Eval as a forward base to get a deeper penetration into the Bay of Biscay.

This particular time four aircraft went to St Eval and as we readied for

takeoff the next morning, with our skeleton ground crew watching, the aircrew

member setting the detonation switches tripped the one for the engine fire

extinguishers. Well that aircraft did not get away that morning and all

day long we ran the

engines and they coughed and coughed and coughed. When

the other aircraft returned and it was time to return to Beaulieu that

evening they were still coughing. The S/Ldr (I forget who he was) put the

faulty crew in his aircraft and taking a volunteer F/E and Nav. decided

to try to get the aircraft home. St Eval is built atop a cliff. The main

runway has a drop of a couple of hundred feet onto the water .As that aircraft

with the engines still missing on occasion charged down the runway and

dropped off the end it seemed a long time until it appeared again out over

the water. It was well beyond the call of duty. Brave lads. Typical 405

press on types. Got home. The rest of us flew home in good aircraft.

From Beaulieu our aircraft left about 4 a.m. to be in

position over the Bay of Biscay before daylight. We were assigned in our

turn to be on takeoff duty to cover any minor repairs needed. Because there

were no Hangars or buildings out on the drome it was a cold unpopular job

which became worse due to the problems discussed in the next anecdote called

the "New Forest".

Beaulieu Airdrome where we operated for four months for

Coastal Command was in the heart of the New Forest and electric power was

in short supply. We had electric lights in the messes but not in the huts

or ablutions. Our nearest ablutions were more than a quarter of a mile

away and that's a long way when your taking short steps. Now we were lucky

as a chemical toilet left by the contractors who were building the drome

was in the woods near our Nissen hut. The New Forest is famous for its

wild ponies but we also had a large old sow pig with a litter who grunted

around in the woods near our hut. Dysentery struck and went around like

wildfire and the chemical toilet was a welcome neighbor. The toilet was

in a small shelter with no door but a change in direction in the entrance

for privacy purposes. This cold rainy dark night one of our guys headed

for the head - if navy terms are allowed - but the old sow was sleeping

in the entrance for protection from the storm. The fellow stepped on the

sow. The sow stood up. The guy went sprawling and between the mud and the

brown stuff he was so dirty and smelly we wouldn't let him back into the

hut until he had walked the distance in the rain to clean up at the regular

ablutions.

No names, no pack-drill. Big Smitty, the large headed

man in the front row, near the center of the Leeming Squadron picture was

our Engineering Officer. He endeared himself to the boys on Beaulieu when

the RAF Station Group Captain complained about the problem caused in the

area because of the arrival of the Canadians. Smitty, a F/Lt, although

badly outranked, told him we were Bomber Command types and did not want

to be on his damn station but now we were there he was bloody well going

to look after us and be thankful we were pulling his ass out of the fire

as his other squadron was useless.

The food at Beaulieu hit all time low. However I guess

the unfinished drome facilities had something to do with it. A WAAF with

no hair, who served us meals, did not help, although often she wore a scarf

over her head. As we are on the subject maybe this is a good time to throw

in the anecdote I wrote on food in early 1980's.

Early in the war, when we were at the permanent dromes

with their brick buildings and compact layout we went to our billet and

picked up our pint mug and irons (knife, fork and spoon) as we went to

and from the airmen’s mess. Later at places like Grandsden Lodge facilities

were widely dispersed and we all carried our mugs and irons in a shoulder

strap bag as we bicycled around the drome from location to location. The

airmen’s mess worked on a four meal ( ?? ) per day system, breakfast, dinner,

tea and supper. About 50% went to breakfast and 5% to supper. The other

two meals were well attended. Breakfast was usually a bowl of porridge,

the milk and sugar already mixed in, and a plate with a piece of boiled

cod fish or some unpalatable item, with a slice of bread (often no margarine)

and a pint mug of tea with the milk and sugar already mixed in. When we

fogged in with no operational meals for several days the eggs (bacon and

eggs were the ops supper favorites) went to the airmen’s mess. Word spread

like wildfire and the breakfast attendance went up to nearly 100%. Now

these eggs (we never saw the bacon) were fried in large pans and cooked

right through. Rubbery as hell but to us a real treat. Might happen four

or five times a year. Most guys missed breakfast because it gave another

half hours sleep and they could get a cup of tea (called a cuppa) and a

bun (no butter or jam) at the NAAFI wagon that drove around the drome at

mid-morning.

Dinner at noon was the main meal of the day and was usually

beef, sliced very thin, and potatoes, gravy and a vegetable. Mostly the

vegetable was Brussel sprouts, hence the name of the book, "Boys, Bombs

and Brussel Sprouts". Dessert was usually a custard about ½ inch

thick above a 1/8 inch layer of jam on top of a crust. You got a square

about two inches each way. During garden season a large help yourself bowl

of lettuce would be available. The standard large pint of tea washed it

down. When newcomers to our hut enquired how I got the scar on the base

of my neck some smart ass usually replied that I got stabbed by a WAAF

as I reached for a second helping. They did not deny us from meanness,

just so it would cover a fair share for all. Some went through a long line

up for seconds but if the servers recognized you they would turn you away.

Tea was around 4:30 and was a light meal, say two sardines

on a slice of toast, something like that. Two slices of bread on top of

which one WAAF plunked a spoon of margarine and another a spoon of jam

was the best part. The ever present pint of tea helped. Now the real artists

came to the fore and to watch a good knife man move the jam to a corner,

spread the margarine, and then rework the jam to produce a good looking

piece of bread was a delight to witness. This had to be done on a bare

board table with no side plate or napkins to help.

Supper was about 8 p.m. and was attended by very few for

the following reasons; It was always soup made from the left overs of the

previous day with plain bread and a cup of tea.

On a dispersed drome it was often a mile away from your

billet, often through the rain. The time was in the middle of the evening,

when you were in town, or at the local pub, or in the middle of the poker

game in the hut.

Parcels from home sometimes provided small snacks which

could be enjoyed in the hut with the local purchased bread which was not

rationed. Usually the people at supper had missed tea due to travelling

back from leave or other reasons and was only considered when starvation

threatened. The bread was always dark and it was against the law to sell

or serve fresh bread. Newspapers reported butchers who went to jail for

putting meat in their sausages and not just soy bean flour. All things

considered we were better off than civilians and very little grumbling

was heard. Food off the camp was hit or miss and even the good restaurants

with the fancy menus ran out very quickly and served spam & chips or

fish & chips to 95% of their customers. Special spots like London's

Beaver Club, where a half hour line up for one doughnut was common, provided

treats and were always a point of call. Rural areas, especially Scotland,

were better off and milk to drink was sometimes available. It reads tough

and points up how spoiled we are now when you remember how well we fared

in those days and how healthy we were.

We guys on the ground crew often wondered how many of

our a/c went down because of Jerry and how many went down because we did

not maintain them well enough. Now we did our very best but still wondered.

When we did our four month stint on Coastal Command I think we only lost

one a/c so that gave us some evidence we were doing pretty well. (WE later

held the Bomber Command Maintenance record on several occasions). We were

flying Halifaxes at the time and they were a bit dicey with front turret...

it got taken off later... improved the a/c a lot. This particular day an

a/c came home on three engines and the idea was prevalent that if you got

a dead engine on a Hally down you'd never get it back up. This pilot asked

for permission for a right hand circuit so he could keep the engine up.

This was not the normal way and coming around he stalled, and plowed in

with the depth charges exploding and the awful results, right there at

the drome with us all watching. This shook up the newer crew members and

nobody believed the Halifax Co. representative who said it need not have

happened. Well S/Ldr Lloyd Logan took up a Hally with a F/E to assist and

he threw that a/c all over the sky. One engine out, two out, every combination

of up, down and sideways. He beat up that drome so low you could count

the rivets on his a/c. Quieted the boys down. Good show.

The road to Brockenhurst where we caught the train to

Bournemouth or Southampton was a little used road through the New Forest

and we biked it all the time with no lights on our bicycles. This night

for some foolish reason the local cop stopped two of our lads on a small

bridge just outside the town and demanded identification so they could

be charged for no lights after dark on their bikes. As they fumbled in

their pockets, stalling for time, two more lads arrived and they picked

up the 'Bobby' and threw him over the bridge rail into the water and then

threw his bicycle over the other side, and hightailed it to camp. This

ride sobered them up and they became concerned later and reported their

misdemeanor to the Squadron authorities who sent them on a swiftly arranged

leave. As a result the week the "Bobby" spent surveying faces at the airmen’s,

sergeant's and officer's messes did not reveal the culprits.

One more story about Beaulieu. During our time there a

movie film was made about Bomber Command. I think that was the title "Bomber

Command". We were all to be sent to the local village for special showings

of this movie. Whether this was to show Bomber Command to Coastal Command

or not, I do not know, anyway there wasn't all that much to be learned

by we who had spent years in the Command. We were sent 25 or 30 at a time

in the back of a 5 ton truck which dropped you off at the cinema and picked

you up immediately following the show. Now the dysentery was still around

at this point and Norm "Roxy" Lawson, a Winnipeger, asked Don McLaren,

a Montrealer to get him some "Ant purgative" during his trip to see the

show. Now Don had to really hustle to accomplish this and not get left

behind by the truck. We were trucked there because it was on the far side

of the drome with no regular bus service. I'm sure it was the only time

I was ever in that town. McLaren gave his order, paid his money, grabbed

his package and ran like hell to catch the truck. When he arrived at camp

he gave Lawson his package and change. Lawson opened it to find he had

a package of condoms. What else would a Canadian go into a pharmacy for?????

Our time in Beaulieu mud ended on March 1, 1943 when we returned to Topcliffe.

Photo credit: http://www.steval.co.uk/archive-items/jean-shaplands-book/

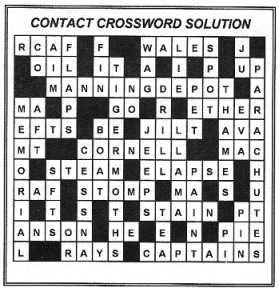

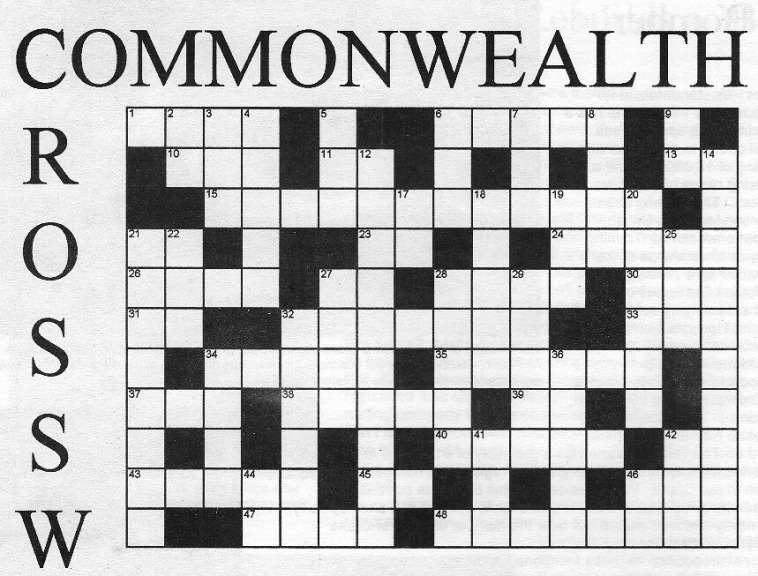

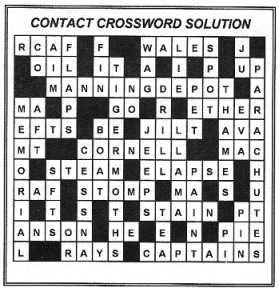

114

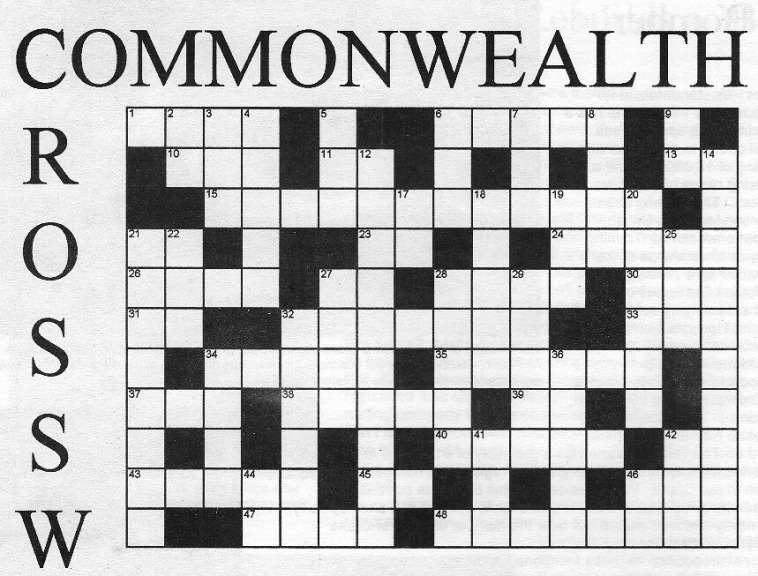

of 150: Commonwealth Crossword

From the Commonwealth Air Training

Plan Museum newsletter CONTACT, Volume 15 Number 2, April 1998, we give

you the Commonwealth Crossword, a test of your knowledge of the vernacular

or the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Unfortunately, we are unable

to give you an interactive online version of the puzzle, but this page

should print well for you. If not, drop me a line at brandonman@msn.com

and I will send a MS Word copy. Answers are at the bottom of the page.

ACROSS

1. Canadian Flyers.

8. Charles, Prince of _____.

10. Engine Lubricant.

11. That thing.

13. Direction aircraft goes on take off.

15. First home for a BCATP trainee.

21. _____ and Pa Kettle.

23. Opposite of stop.

24. Used to start a frozen engine.

26. Where the Cornells and Tiger Moths are (Abbr.)

27. To _____ or not to be _____.

28. Leave a lover.

30. _____ Maria.

31. Home of fuel and fire tenders, jeeps and staff cars..

32. Tiger Moth replacement.

33. #1 American in the Pacific (Abbr.).

34. Power behind old-style locomotives and ships.

35. To slip by, i.e. time.

37. British Flyers.

38. What Allied flyers did to the Luftwaffe.

39. Pa Kettle's wife.

40. Something you don’t want on your dress uniform.

42. This and good food gives BCATP trainees healthy bodies.

43. Twin engine favourite of BCATP trainees.

45. That man.

46. A favourite dessert in the mess.

47. Sun or 'x.'

48. James Cagney was one of these ________Of The Clouds.

DOWN

2. The man in charge.

3. You better do this right or the bombs fall short.

4. These give extra lift when taking-off or landing.

5. A stabilizer on a fish, submarine or aircraft; a fiver;

neighbour to a `Swede,’

6. A sharp-shooting radio-operator.

7. Something that isn’t true.

8. _____light or Dick & Jane’s dog.

9. Abbreviation for a German Aircraft type (look around

this page).

12. The first flying love for most BCATP trainees.

14. Wise aircrew don’t leave a disabled flying aircraft

without one of these.

17. Opposite of yes.

18. To learn through repetition, e.g. marching.

19. A special animal.

20. London’s river.

21. The Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum’s book.

22. Not forward but _____.

25. Adolph’s girlfriend.

27. Canso or PBY is a flying _____.

28. All-terrain four-wheel drive vehicles – our’s is

RCAF blue.

29. South American version of a camel.

32. Where BCATP Cranes come from.

34. Where BCATP pilots get their advanced flying training.

36. It’s blue on the bottom of Hurricanes and Spitfires.

41. Next to beer or gin, favourite beverage of the RAF.

42. At the wing’s parade, the CO will _____ your wings

on your tunic.

44. and/_____.

46. Favourite dessert in math class.

115

of 150: A WWII Memory - June Bollman

As the Commonwealth Air Training Plan

Museum has a project to gather names and stories of those who took part

in the World War II years, may I add a short story.

Before the war, I took a business course in New Westminster

B.C. which led to a position of keeping records of inventory in a store,

which was a learning experience.

Then World War II comes into being and the public was

encouraged to help in any way they could. I applied for a position at the

Canadian Pacific Repair Depot which was on an island in the Fraser River

near New Westminster.

The Canadian Pacific Repair Depot was an RCAF organization.

This depot took up the message to help the war effort and accept Air Force

planes to be repaired. The depot hangar was close to the Fraser River so

there were not runways to bring planes in for repair. The planes were brought

in on a barge and unloaded on a ramp and towed to the hangar.

The Canadian Pacific Repair Depot was an RCAF organization.

This depot took up the message to help the war effort and accept Air Force

planes to be repaired. The depot hangar was close to the Fraser River so

there were not runways to bring planes in for repair. The planes were brought

in on a barge and unloaded on a ramp and towed to the hangar.

Many elementary training planes were repaired here. It

was very handy for the PBY and other aircraft that were on patrol at the

west coast at that time.

I was assistant to keep records of the inventory of aeroplane

repair parts. Records were recorded on the cards in an office. The parts

were in the work shop area. New equipment coming in were recorded in the

office. When parts were used – said records were forwarded to the office.

The office worked on two shifts – that is 8:00 to 4:00

and the evening shift 4:00 to 12:00 pm midnight. I worked two weeks on

one shift then changed to the other shift. In this office there were the

manager and his secretary. The secretary had a typewriter and not electric.

As more planes came in for repair – more staff was hired.

The office was instructed to teach the new employees. Soon I was assigned

to day shift which was a promotion. Again in this office there were no

computers so all the information was hand printed on the file cards. All

parts have numbers – for example – a wing could have four numbers while

the nuts and bolts could have six or eight numbers.

The noise was most evident with the rivetting, sawing

and drilling from the work shop and the hangar. If the electric power was

shut down – there was silence – no drills and hammers etc. Also no worrying

about losing records on computers.

Frequently there would be a fire alarm and it meant everyone

was to evacuate immediately. We did not know if it was practice of a true

fire. Even at that time – smoking was not allowed anywhere in the building.

Each area had to gather in a certain area outside to be counted. At one

drill – a lady was missing and causing a concern – she soon appeared in

a hurry and explained that she was caught with her pants down!

After the war – the repair depot did not have as many

planes to repair and so my position and many others were eliminated. I

heard a few years later that the depot was closed and all buildings removed.

I returned to the same store in New Westminster where I had been before

the war.

In review – I had met Frank K. Bollman at a dance and

we saw each other whenever possible as he was stationed in Boundary Bay.

When the war was over he returned to the home farm at Moline (Manitoba)

and his Father retired to live in Brandon. We were married and continued

to farm on his Father’s land. We have two children – Raymond and Elaine

and that is another long story. Now we live in Brandon and Frank is involved

with the Commonwealth Air Training Plan

Museum.

June Bollman

June passed away in August 2010 at the age

of 87 years.

Click for full-size promo collage poster

Frank

McManes and his wife Shirley were charter members of the Commonwealth Air

Training Plan. He, like many other young men of the prairies, joined the

Royal Canadian Air Force in World War II.

Frank

McManes and his wife Shirley were charter members of the Commonwealth Air

Training Plan. He, like many other young men of the prairies, joined the

Royal Canadian Air Force in World War II.