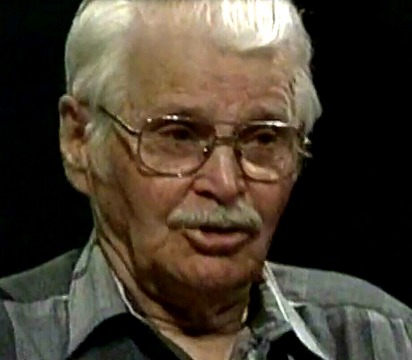

Jack Stacy was a Founding Member and Past-President

of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum.

He enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force and after

completing training at No. 2 Manning Depot in Brandon and No. 3 Bombing

and Gunnery School in Macdonald Manitoba, he was stationed in in Yorkshire

England where he flew with a Halifax crew as a mid-upper gunner.

Jack gives a great accounting of operations on

a Halifax aircraft and as an air gunner.

Jack died in May 2009 at the age of 84 years.

His Oral History Video can be seen at:

https://youtu.be/lvBX92zusEs

122

of 150: RCAF Drama on Main Street -- Moose Jaw

DOWNTOWN PARADE – We’re told that this photo was taken in

downtown Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan during World War II. The Westland Lysander

(numbered V9312) and three airmen in front of it indicate that the RCAF

had something to do with this ceremony. In front of them is a statue, which

appears to be a rendering of either William Lyon Mackenzie King or Winston

Churchill, but it would seem premature to be honoring either man prior

to war’s end.

DOWNTOWN PARADE – We’re told that this photo was taken in

downtown Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan during World War II. The Westland Lysander

(numbered V9312) and three airmen in front of it indicate that the RCAF

had something to do with this ceremony. In front of them is a statue, which

appears to be a rendering of either William Lyon Mackenzie King or Winston

Churchill, but it would seem premature to be honoring either man prior

to war’s end.

The troops facing the statue and aircraft appear to be

soldiers – with the exception of the NCOs and officers, each man appears

to be wearing putties and holding a rifle complete with bayonet. Each man

is also wearing a wedge cap, but these were standard issue in both the

air force and army. There is a band to the right of the troops.

Recognizable business names on the street include James

Richardson and Sons, Malden Coal, Sterling Shoes and the Park Hotel. A

Sweet Caporal Tobacco sign hangs from one of the businesses.

If anyone has any idea what drama this picture is capturing

or if you disagree with our speculations – perhaps you were there or also

have photographs and the history of this story – drop us a line, we’d love

to know.

If you have a photo related to the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan or the RCAF during World War II, please give us a call.

We’d love to have these precious artifacts as a donation for current and

future generations to savor. If you can’t part with it permanently please

consider lending it to us for a very short time so we can make copies.

This artlcle first appeared in the Commonwealth Air Training

newsletter CONTACT. We were

unsure of the location of this ceremony but new information found on the

Aircraft Restoration Company at Duxford, England web site (www.aircraftrestorationcompany.com/projects)

states that Lysander V9423 arrived in Canada on October 18, 1942 to serve

at No. 2 Bombing and Gunnery School in Mossbank Saskatchewan. This gives

credence to the idea that this ceremony took place at Moose Jaw which is

a scant 37 miles from Mossbank by air. The Aircraft Restoration Company

is bringing V9423 back to life. Take a look at their web site – they are

doing some great work.

More information about he Lysander at:

www.warbirdregistry.org/lizzieregistry/lizzie-v9312.html

https://get.google.com/albumarchive/107238265313281486528/album/AF1QipOFjsFKRpAXndrMuoJHHWZBq-VvLIef1OWEGEPL

www.flickr.com/photos/richard64pics/14373738713

123

of 150: The First Steps for a RCAF Wireless Air Gunner

TURNING A PAGE

Excerpted from The Long and the Short and the Tall

by Robert Collins,

published in the Legion Magazine, December 1986.

Robert Collins

Never

in my life have I been in such a motley crowd - or felt so totally alone.

I am surrounded by 750 naked and half-naked men. Skinny men, plump men,

Greek gods. Men in boxer shorts, dirty shorts and no shorts. Men with body

odor that would fell an ox. Men brooding silently on their bunks. Men shouting,

laughing, punching biceps, breaking wind, cursing, telling world-class

dirty jokes that would leave the wise guys propped up outside the pool

hall back home mute with awe and admiration. Apart from a nodding acquaintance

with an acne-ridden Toronto youth across the aisle, who proudly informs

me that he's had syphilis three times - I am very careful not to shake

hands - I know none of them.

Never

in my life have I been in such a motley crowd - or felt so totally alone.

I am surrounded by 750 naked and half-naked men. Skinny men, plump men,

Greek gods. Men in boxer shorts, dirty shorts and no shorts. Men with body

odor that would fell an ox. Men brooding silently on their bunks. Men shouting,

laughing, punching biceps, breaking wind, cursing, telling world-class

dirty jokes that would leave the wise guys propped up outside the pool

hall back home mute with awe and admiration. Apart from a nodding acquaintance

with an acne-ridden Toronto youth across the aisle, who proudly informs

me that he's had syphilis three times - I am very careful not to shake

hands - I know none of them.

It is 10 p.m., Sept. 11, 1943, bedtime at No. 2 Manning

Depot in the bowels of the Brandon, Man., Winter Fair building, commonly

known as the Horse Palace. What madness made me leave my safe and gentle

Saskatchewan home for this barn full of rude, nude, raucous strangers?

I have been in His Majesty's Royal Canadian Air Force

precisely 36 hours and here at manning a mere six. But already my mother,

father and brother, and the farmhouse where I have lived for all of my

19 years, seem lost forever. Where are those long-awaited pleasures of

being an airman? Where are those handsome, laughing fellows from the recruiting

posters, in tailor-made uniforms with wings on their chests, beneath the

seductive words "WORLD TRAVELLER AT 21?" The posters never mentioned the

Horse Palace.

In peacetime this building housed prizewinning horses

and cattle. The troughs for flushing away their manure are still in the

grey cement floor a few inches below my head. Is the air force trying to

tell me something? So far, we have moved in herds like Old Reddy and Whiteface

and the other cows back home. Nobody has made me feel welcome or wanted.

By turns, I am scared, confused, exhilarated. We 1,500 new and fairly new

recruits are bedded down on two floors, among infinite vistas of double-decker

metal bunks. We are a cross-country sampler: the air force ships its basic

trainees to wherever there's room in one of the four mannings - Brandon,

Toronto, Edmonton, or Lachine, Que.

There are easterners among us - a rare exotic species.

I've never really known an easterner. Will they be snobs? bullies? smarter

than me? For the moment that's irrelevant. What matters is that I and five

other pieces of human raw material who shambled off the train this Saturday

afternoon are the greenest of all.

We have no uniforms yet-the depot stores are closed. Not

only are we visibly new, but our clothes betray our backgrounds. Mine -

a cheap and sombre brown suit, the only one I own, and a salt and pepper

cloth cap say rural hick. Or so I think, which is all that matters tonight.

Earlier this evening, in our telltale civvies, we stepped

timidly into the vast mess-hall. I had never before been to a cafeteria

or even a summer camp. I had eaten en masse only at rural schoolhouse

socials or at my mother's dinner table with 10 or 12 other men at threshing

time. In those places, the menfolk sat stuffing their faces while the womenfolk

eagerly served them.

Here, we tentatively followed the leader to trays, plates,

cutlery, down a long line of steam tables and kettles where indifferent

airmen in white ladled out - what? Stew maybe. Plentiful and probably nourishing,

but bland and anonymous. Fleetingly, I longed for my mother's roast chicken,

served on her dinnerware with the little primroses around the edges that

I'd eaten from all my life. I read the derision in the mess crew's eyes:

Better get used to it, airman, your mommy ain't waiting on you now.

We huddled at long trestle tables in the perpetual din

- loud voices, clashing cutlery, shouts from the kitchen - not quite finishing

our food. The uniforms around us gulped their meals like boa constrictors

they never seemed to chew - and we didn't want to be different. Afterward,

just time to get blankets and sheets - You bastards are lucky; the army

don't get sheets! Then, into this sea of humanity, the Horse Palace. Everything

is huge, chaotic, astonishing. And as on all first days in life - first

day at school, first day at camp, first day at the office - we know, we

are certain, that all the others are watching us, measuring us, laughing

at us.

Now, thank God, it is bedtime. Surely tomorrow we'll get

uniforms and blend in. The Lights are out. The great echoing room is subsiding,

like a large beast that bas turned around three times in the weeds and

curled up for the night.

In my whole Life I have never slept in a room with more

than one other person - the cubicle of a bedroom I shared with my younger

brother, Larry, with only the sighing of wind through the poplar tree belt,

or a coyote somewhere far out in the stubble, or the welcome boom of thunder

that meant the end of drought, or on winter nights the eerie hum

of frost-caked telephone lines, singing, singing, singing.

Gradually my nerve ends stop jangling and then, a piercing

cry: "F- - - the East!" And instantly, as though on cue: "F- - - the West!"

Others take up the chorus, a cacophony of ribald shouts ricocheting off

the cement floor, the high ceiling, the metal bunks.

What's going on? Sure, I know there is East-West rivalry.

All of us from Saskatchewan routinely hate Toronto, knowing with sweet

certainty that it is rich, privileged, and scornful of us stubble-jumpers.

We graduates of the Depression remember the boxcars of free Ontario food

and clothing with mixed gratitude and resentment. Charity from the East!

None of us can forget the carloads of Maritimes dried codfish, sent with

good intentions - and the texture and taste of salted boot leather. But

even so. And that word! Even my father, a virtuoso swearer with a

wide repertoire, never used the F-word. My mother, a devout church-goer,

never said anything stronger than "darn." Even at school the word was used

only sparingly, by really bad boys, the kind your mother said you mustn’t'

play with. And then only in huddled dirty talk behind the horse barn, the

rest of us listening wide-eyed while the girls, ears straining, hovered

watchfully on our periphery, hoping for something incriminating to report

to the teacher.

But now a weary voice, maybe a corporal's, cuts through

the racket. "Awright, you bastards!" The room settles down with sighs,

snorts, chuckles, mutterings and comfortable grunts. Now I understand.

This is a nightly ritual, our bedtime story. For the first time I feel

a hint of belonging to something. Nothing dramatic or heroic like standing

shoulder to shoulder to fight Hitler. Most of us are here for patriotic

reasons but we would never admit it in the company of strangers. We are

far from the hated enemy and may never lay eyes on him.

No, our adversaries, for now, are the system that already

has turned us into numbers and is about to mould us into marching machines,

and the corporals and sergeants who will strive to maintain their proud

reputations as mean sons of bitches.

Already I sense the adversarial system from the non-commissioned

officers strutting around this bam and from the cynical gibes of recruits

who've been here three or four days. Already we are united against It and

Them, and against our loneliness and apprehension. It is a scrap of comfort

at the

end of a bewildering day.

This concludes Part 1 of Turning the Page, the

recollections of Robert Collins on the start of his journey to become

a Wireless Air Gunner in the Royal Canadian Air Force in World War II.

The conclusion of his story will appear in the next CATPM Canada 150 Vignette

as Part 2.

Read all monthly issues of SHORT BURSTS

The monthly AG and WAG Magazine from 1983-2008

www.airmuseum.ca/mag

124

of 150: The First Steps for a RCAF Wireless Air Gunner - Pt. II

In the first installment of "Turning a Page," Robert

Collins recounted his early experiences with enlistment in the Royal Canadian

Air Force and training in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. His

story continues with an emphasize on the thoughts of him, as a young, naive

farm boy, and his family facing the prospects a son might encounter in

the war.

September 11, 1943 – No. 2 Manning Depot, Brandon Manitoba

– A kaleidoscope of thoughts and memories whirled through my mind. Why

was I here? That was easy. Partly because, a generation before, a short,

feisty, Belfastborn, English-raised patriot named John Douglas Collins

- my father - had left his newly acquired Saskatchewan homestead the moment

WW I was declared, joined Lord Strathcona's Horse, gone overseas with the

first Canadian contingent, and the following spring marched into the front

lines of France, sans horse, like the rest of his regiment.

September 11, 1943 – No. 2 Manning Depot, Brandon Manitoba

– A kaleidoscope of thoughts and memories whirled through my mind. Why

was I here? That was easy. Partly because, a generation before, a short,

feisty, Belfastborn, English-raised patriot named John Douglas Collins

- my father - had left his newly acquired Saskatchewan homestead the moment

WW I was declared, joined Lord Strathcona's Horse, gone overseas with the

first Canadian contingent, and the following spring marched into the front

lines of France, sans horse, like the rest of his regiment.

That autumn he was carried out, sick and bloated: from

the late-spring Battle of Festubert; from a summer of ice and mud and relentless

shell-fire; from poison gas and the inhuman trenches. After a long convalescence

in England they sent him home, with orders to work outdoors if he

wanted to stay alive. He went back to farming his 320 acres. He was a literate

man with a profound distrust of things mechanical.

He'd have been ill-suited for farming even with good health.

Now a friend met him at the train, looked at his face, aged and wrinkled

before its time, and wept. "My God, Jack," he said. "What have they done

to you!"

My father's war never really ended. Physical ills and

bad memories plagued him. He rarely talked about it, and never with the

affection and nostalgia of many veterans. But once, when my brother and

I were small, we coaxed him to show us how a cavalryman rode. He was in

his 50s, cursed with lumbago, but he vaulted on our bemused saddle-horse

and, sitting straight as an arrow, cantered her around the farmyard to

our total delight, and his.

Sometimes he would snap us a salute and we'd snap one

back, everyone laughing. And once, shortly before he died in the Vancouver

veterans hospital in 1957, of age and the residual damage of the war, he

confusedly barked out military commands from 42 years before. That day,

no one laughed.

Despite what the war did to him, his patriotism never

wavered. He believed in the Royal Family and the Empire as fervently as

he despised Mackenzie King, the Liberal party and socialism. When WW Il

broke out, he wanted to enlist, which would have been laughable had be

not been deadly earnest. He was far too old and frail to serve even in

the Veterans Guard.

He, and we, listened to the radio war news several times

a day. We sat hushed and reverent when Winston Churchill's fighting speeches

crackled through from London. Once Churchill visited Ottawa, spoke to Parliament,

and derisively told how the boastful Hitler had threatened to wring England's

neck like a chicken's. "Some chicken!" Churchill's voice rang over the

airwaves, and in our living room we joined in the gales of laughter

from the MPs and senators. And then, with his impeccable timing, " ...

Some neck!" I would gladly have risen up and marched to battle beside Churchill

that day.

I clipped maps from the Regina Leader Post, charting every

rise and fall of Allied fortunes. My father never urged me to enlist; I

think he dreaded it. But I owed it to him. I knew that if I joined up he

would be burstingly proud. And he was. It was not just my father's influence

and example. My family and most of our neighbors were caught up in the

drama and adventure of WW II. We were certain that it was a just war. Hitler

had forced it so we were going to beat him. There was urgency and camaraderie

in the air. You gave blood to help a wounded soldier. You dropped coins

into milk bottles on grocery store counters to buy "Milk for Britain."

We salvaged everything. Old pots and pans, toothpaste tubes, and the tin

foil from cigarette packages, for their aluminum; leftover fat , for the

glycerine in high explosives. My school friend Mac Smart and I canvassed

local farms for rusting and abandoned machinery, lugged backbreaking tons

of it into a truck, and sold it to make guns or God knew what, loyally

donating the money - about 6,000 cigarettes' worth - to the cigarette fund,

an endless tide of nicotine for our fighting men. Food, gasoline, beer

and hard liquor were rationed. This didn't matter much: We grew most of

our food, rarely drove our 1929 Chev, and never let booze pass our lips,

mother abhorring it and father abstaining because of his health. But rationing

made us feel closer to the war afar.

The radio, newspaper and magazines brought that distant

war to Shamrock. I saw photos of overalled women in munitions factories,

their curls tied up in head scarves, never dreaming that I was witnessing

women's liberation. Advertisements showed little girls with fingers to

lips, cautioning: Please! A War Worker Is Sleeping. The radio played Milkman,

Keep Those Bottles Quiet and When the Lights Go On Again and we sang along,

although I'd never seen a milkman or a blackout.

All around us young men and women were trickling into

the forces. Big, husky Roland Hook, from a couple of miles south, joined

the army and the fighting in Europe. Handsome, swarthy Earl Brown joined

the air force and lost his life on a mission not so long after our school

played softball against his. My cousin Dora enlisted in the RCAF Women's

Division. My high school friends, the inseparable Henry twins, separated

to join the navy and the army.

With my father's health failing, I could have opted to

be an essential farm worker, exempt from military service, as many friends

did. But I would have been a terrible farmer. I was a bookish, skinny,

unathletic scarecrow, not much good at anything except school. I loved

the land but I wanted to be a writer.

This didn't make me a Grade A candidate for soldiering.

Nor was I brave, but bravery or lack of it was almost incidental. Given

the mood, it took more courage to stay home. One neighbor - a kind, polite,

hard-working fellow several years older than I who kept a watchful eye

over me in my first year at grade school - went to jail rather than abandon

his religious principles about war. I knew he was not a coward, but others

didn't. It caused a flurry of oohs and ahs over the party line. The war

was duty but also high romance, and the RCAF was the newest, most glamorous

of the services.

Everything exciting seemed to be happening in the air.

My father's nightmare in the trenches had soured me on the army. The navy

seemed a bad bet because I couldn't swim. But the air force! Harvard and

Anson and Tiger Moth trainers from airbases at Mossbank and Moose Jaw sometimes

flew over our fields. I craned my neck at them, awed and wistful.

Most important, my special pal Roy Bien was already a

wireless air gunner. To me, it was the ultimate in glamor: He manned the

guns in battle and at other times operated that fascinating instrument,

the wireless radio. He was three years older but we had often walked

home together from grade school. I worshipped him – the way he danced,

played the guitar and yodelled, got the girls. When he came home on leave

with the WAG's white half wing on his blue chest, I was consumed with envy.

It had to be the air force.

All of this was impossible to put into coherent words.

Not yet 18 when I finished Grade 12 - the end of high school in Saskatchewan

- I mumbled to my parents: "Guess I'll be joining up soon." My father

nodded. "I guess we knew you would." My mother, looking fixedly at her

sewing, said quietly: "What would you do, son?" "Something like what

Roy's doing." None of us said much more at the time. My mother's face was

taut and troubled. It was not that we expected me to die in battle.

It was simply that our little foursome was breaking up. We had done everything

as a family. Even in the depths of the Depression, there had been a comforting

sameness and unity to our lives. Now nothing would ever be the same again.

That summer my father had a chance for local work, managing

Shrunnck Lumber yard. The wheat and oats that summer of 1942 were the best

we'd seen in years. He took the job and I promised to stay on long enough

to help harvest the crop. An early autumn snow caught the stooks I had

made before we could thresh them. Through the fall and winter I ran the

farm and all its livestock reasonably well, with my mother's and brother's

help. In the spring we belatedly threshed, then arranged to rent the place

to neighbor Tommy Hawkins.

Then it was definitely time to go to war. Roy Bien had

just gone overseas. Armed with air force recruiting literature, I hitched

a ride to Moose Jaw, 60 miles from home, with Tim Adams, the gentle, cultured

Englishman who ran our village post office. Mister Adams, as we boys were

taught to address him, knew everything about the world, or so I thought.

For my first night in a hotel he recommended the respectable Harwood. Its

advertisement tantalized with " 110 rooms, 35 with bath, every guest room

with own private toilet; soft water" for $1.50 single.

The next morning I presented myself to the RCAF in the

Hammond Building on Main Street. They languidly filled out forms and instructed

me to report to No. 5 Recruiting Centre in Regina two weeks later. Those

two trips set a new record for personal travel: Until then I'd been on

a train and in a city only once.

The Regina recruiters were equally unmoved by my presence.

By 1943 the air force had plenty of applicants, and I was no bargain. My

medical exam proved me basically sound, although more like a famine victim

than the handsome hunks in the recruiting posters: 5 ft. 11, 125 lb. with

a 31-in. chest and sparrow's ankles. Then they handed me the color-vision

test-pages of bewildering colored dots that revealed certain numerals to

the medically fit. I saw no numbers, or the wrong ones. I was blue-green

color-blind! "Definitely unsafe," said the medical officer, for aircrew

or ground duty involving colored wiring or lights.

I was stunned, flabbergasted, desperate. I could not be

like Roy Bien. I could not even learn radio, which was part of my dream.

The air force was yanking everything out from under me. I'd had no inkling

of faulty color vision. I could tell red from green from blue! But because

they said I couldn't, the only options were cook or airframe mechanic.

A cook? I could never face Roy again.

Yet it had to be the air force. Airframe mechanic was

OK; it meant tinkering with all parts of a plane except the engine. As

a farm tinkerer I reckoned I could cope with that. They gave me a mechanical

aptitude test. I scored 30 out of 100. A corporal gazed at my score in

disbelief. "Sure you don't wanna be a cook, kid?" he said.

But Fit. Lt. W.C. Cumming was more charitable when he

saw my high school marks. My wonderful Grade 12 teacher, Richard Schmalenberg,

had coached and inspired me to a strong finish: a 78.4-percent average

including, predictably, As in literature and composition and, unpredictably,

more As in the subjects I hated trigonometry, chemistry and geometry. Cumming

also liked my classification test score. The CT, which assessed "basic

intellectual suitability," covered 80 points of mental ability, ranging

through perceptual alertness, numerical sense, ability to follow directions,

verbal sense and reasoning ability. ln the 30-minute time limit I scored

71 out of 80, about 20 more than the average graduate.

"An above-average rural lad-intelligent, co-operative,''

Cumming wrote on my form . " While MAT (mechanical aptitude) score is low,

CT is high and has a good academic record. Believe he is well worth a try."

So I was accepted. Still smarting, I begged a different color test for

a week later. At home during the interim, my peaceable mother turned into

a tiger. How dare the air force say her boy was defective! But back in

Regina the results, retested with pin-point colored lights, were

the same. "Go home and finish the harvest; you'll be needed there,'' the

recruiters said. "Report to Brandon manning pool in the fall."

Being an intelligent, co-operative rural lad, I did. I

stooked more grain, pitched more sheaves and wondered, with mingled

glee and fear, what was ahead. Then, one crisp September morning, I left

my mother in tears beside the big flat stone that was the back doorstep

of our farmhouse. She who had stayed cheerful through a life of hard times.

She of that strong, stoic, God-fearing, Pennsylvania Dutch stock named

Hartzell. She who'd grown up on a hard-scrabble North Dakota farm, won

a scholarship to university but never had a chance to use it, begun teaching

at 18 to help support her mother, and met Jack Collins, the love of her

life, during a class-room stint in Saskatchewan. All through the awful

years of the Depression, all through dust and grasshoppers and no crops

and no money, I'd seen her cry only once before.

I left my father at Shamrock's depot, a carbon copy of

all the little dull-red clapboard CPR depots across Canada. He was an articulate

man, and never ashamed to show emotion, but this moment was too painful

for both of us. We gripped hands, hard. He squeezed my shoulder once. We

murmured words. The train jerked away. I looked back, with an ache in my

throat. He stood rigid on the wooden platform, his shoulders a little slumped,

his normally cheerful face set grim and valiant.

In Regina the next day - by chance, it was my 19th birthday

- I stood with a handful of others before the Red Ensign and intoned: ''I,

Robert John Collins, do sincerely promise and swear that I will be faithful

and bear true allegiance to His Majesty." Now I was R2*****, Collins, R.J.

The next morning I boarded the 8:55 CPR main-line train for Manitoba, clutching

two military meal tickets entitling me to breakfast and lunch. When I laid

out a ticket after my first meal in a dining car the steward sighed noisily

and raised his eyes heavenward: Oh Lord, why have you sent your humble

servant this miserable wretch? ''You shoulda given me that before you ordered,"

he scolded. This traveller was just another dumb recruit, he realized the

chances of a tip were nil.

Then getting off at Brandon, a whole province away, clinging

to my father’s worn black club bag, I gravitated uncertainly to a sign

at the end of the platform - AIRFORCE RECRUITS ASSEMBLE HERE. A corporal

scooped me up with five other lost souls. "A wright, you men, follow me.’’

Bored with his menial task and not bothering to try marching the likes

of us, he led us in a straggle to Pacific Avenue about half-mile straight

up Tenth Street. Passers-by scarcely gave us a glance; this little city

was teeming with airmen. In minutes we crossed Victoria Avenue to the ornate

front of the arena and winter fair building - two stories and a great arched

roof with long deep windows, my first of many homes away from home.

As we timidly past the armed sentries into the enormous

maw, a few airmen chanted "You'll be sorr-eee!" We smiled weakly sensing

correctly that it was a mandatory warning for all newcomers. It was a clear

I'd hear often in the years ahead but it seemed especially apt this night.

Later, nearing sleep. I have one brief memory of humanity

amidst the chaos. As we readied ourselves for bed, we newcomers fumbling

through the unfamiliar routine - Which way to the john? Does anybody brush

his teeth? Where do you hang your clothes? Does anybody wear pyjamas? -

a young man with a long, lean face and prominent nose dropped to his knees

before lights out, folded his hands, bowed his head and silently prayed.

My heart went out to him. I had not been taught to pray beside my bed but

I would never have had the guts to do this before this crowd of noisy profane

strangers. There were a few sidelong glances, grinning winks, a surreptitious

whisper or two, but no one baited him. His courage of conviction that first

night was a good thought to go to sleep on.

A graduating class outside against the brick walls of No. 2 Manning

Depot

Never

in my life have I been in such a motley crowd - or felt so totally alone.

I am surrounded by 750 naked and half-naked men. Skinny men, plump men,

Greek gods. Men in boxer shorts, dirty shorts and no shorts. Men with body

odor that would fell an ox. Men brooding silently on their bunks. Men shouting,

laughing, punching biceps, breaking wind, cursing, telling world-class

dirty jokes that would leave the wise guys propped up outside the pool

hall back home mute with awe and admiration. Apart from a nodding acquaintance

with an acne-ridden Toronto youth across the aisle, who proudly informs

me that he's had syphilis three times - I am very careful not to shake

hands - I know none of them.

Never

in my life have I been in such a motley crowd - or felt so totally alone.

I am surrounded by 750 naked and half-naked men. Skinny men, plump men,

Greek gods. Men in boxer shorts, dirty shorts and no shorts. Men with body

odor that would fell an ox. Men brooding silently on their bunks. Men shouting,

laughing, punching biceps, breaking wind, cursing, telling world-class

dirty jokes that would leave the wise guys propped up outside the pool

hall back home mute with awe and admiration. Apart from a nodding acquaintance

with an acne-ridden Toronto youth across the aisle, who proudly informs

me that he's had syphilis three times - I am very careful not to shake

hands - I know none of them.

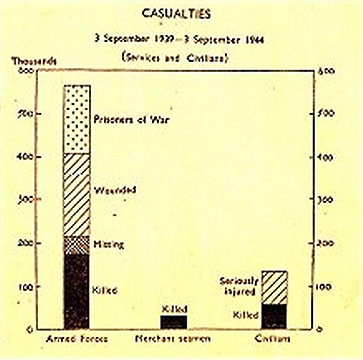

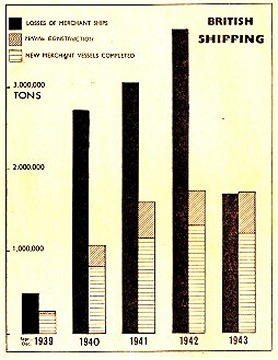

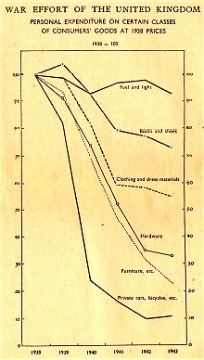

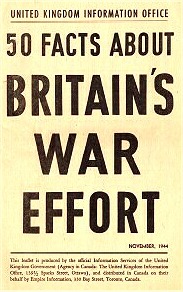

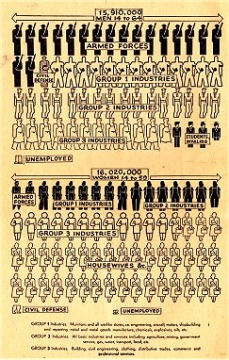

For

more than five years, military security prevented Britain from revealing

anything like a full picture of her war effort. To have given away detailed

figures on manpower, production, food and other matters might have enable~

the enemy to piece together some of the secrets of Britain's survival,

and to use this information in preparing further attacks on the island

which had defied ·the Nazi plan for world conquest. Britain is still

subject to attacks; but the Allied position is now secure, and many facts

and figures of Britain at war can be neither of aid nor of comfort to the

enemy. On November 28; 1944, the British Government lifted ,the curtain.

For the first time, the world was able to look into the military camps,

the factories and the homes of Britain.

For

more than five years, military security prevented Britain from revealing

anything like a full picture of her war effort. To have given away detailed

figures on manpower, production, food and other matters might have enable~

the enemy to piece together some of the secrets of Britain's survival,

and to use this information in preparing further attacks on the island

which had defied ·the Nazi plan for world conquest. Britain is still

subject to attacks; but the Allied position is now secure, and many facts

and figures of Britain at war can be neither of aid nor of comfort to the

enemy. On November 28; 1944, the British Government lifted ,the curtain.

For the first time, the world was able to look into the military camps,

the factories and the homes of Britain.

1. As early as

mid-1941:, ninety-four out of every hundred males in Britain aged 14 to

64 had been mobilized in the Services or industry. The remaining six per

cent are almost elderly,schoolboys, students, war invalids, sick and retired

persons.

1. As early as

mid-1941:, ninety-four out of every hundred males in Britain aged 14 to

64 had been mobilized in the Services or industry. The remaining six per

cent are almost elderly,schoolboys, students, war invalids, sick and retired

persons.