028 of

150

BCATP A World War II Memory: Stan Reynolds - Pilot

- Part 1 of 3

In

December 2000, the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum received this

air force history from Stan Reynolds. It is one chapter out of a book commissioned

by the Alberta Department of Culture commemorating the 50th anniversary

of the end of hostilities in World War II. The book is "For King and Country

– Albertans in the Second World War" and Stan’s chapter was in the Albertans

Overseas section.

In

December 2000, the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum received this

air force history from Stan Reynolds. It is one chapter out of a book commissioned

by the Alberta Department of Culture commemorating the 50th anniversary

of the end of hostilities in World War II. The book is "For King and Country

– Albertans in the Second World War" and Stan’s chapter was in the Albertans

Overseas section.

Stan entitled his chapter: "From Air Training

to the Defence of Britain: One Pilot's View From Tiger Moths to Mosquitoes."

It is a fascinating by story but much too long for

one Canada 150 Vignette so we have split it into three Vignettes with each

covering Training in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, Training

Overseas in an Operational Training Unit and Air Operations overseas.

Part 1 – Training in the British Commonwealth Air

Training Plan

The

Reynolds family of Wetaskiwin has always been interested in aviation. My

father, Edward A [Ted] Reynolds, was a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps

during the First World War. My older brother, Byron E. [Bud] Reynolds,

joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940, and completed a Tour of Operations

as a flight engineer on Catalina flying boats. My younger brother, Allan

B. [Bert] Reynolds, joined the RCAF in 1943, and served overseas as an

air-frame mechanic on Dakotas [C-47s] with 437 Squadron. When I was sixteen

years old I joined the Edmonton Fusiliers and trained with E Company at

Wetaskiwin during periods that did not conflict with school hours. The

two weeks' training at Sarcee Camp in Calgary during the summer months

was a great experience, with sleeping in tents and target practice with

Ross rifles. In 1941 I was hired as a truck driver for MacGregor Telephone

& Power Construction Co. of Edmonton during the time they were installing

power lines at the RCAF stations at High River, Claresholm, De Winton,

and other locations.

The

Reynolds family of Wetaskiwin has always been interested in aviation. My

father, Edward A [Ted] Reynolds, was a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps

during the First World War. My older brother, Byron E. [Bud] Reynolds,

joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940, and completed a Tour of Operations

as a flight engineer on Catalina flying boats. My younger brother, Allan

B. [Bert] Reynolds, joined the RCAF in 1943, and served overseas as an

air-frame mechanic on Dakotas [C-47s] with 437 Squadron. When I was sixteen

years old I joined the Edmonton Fusiliers and trained with E Company at

Wetaskiwin during periods that did not conflict with school hours. The

two weeks' training at Sarcee Camp in Calgary during the summer months

was a great experience, with sleeping in tents and target practice with

Ross rifles. In 1941 I was hired as a truck driver for MacGregor Telephone

& Power Construction Co. of Edmonton during the time they were installing

power lines at the RCAF stations at High River, Claresholm, De Winton,

and other locations.

The crews slept in tents and my job was driving and looking

after MacGregor's 1928 Ford one-ton truck. At this time a local fellow

Dallas Schmidt, home on leave from the RCAF, stopped at my father's garage.

I was impressed to see him in his officer's uniform. That dapper uniform

and his enviable war record probably increased my desire to join up. Dallas

Schmidt received two Distinguished Flying Crosses and was promoted to the

rank of Flight Lieutenant while flying Beaufighters during the Defence

of Malta. I was in the process of finishing my grade 12 education when,

early in 1942, an RCAF recruiting group came to Wetaskiwin and set up a

desk in the Driard Hotel. Curiosity and my desire to learn how to fly prompted

me to visit the recruiting officer. I was told that I could enlist in the

"Pilots and Observers" category, and if I passed the required tests I would

be selected for training as a Pilot or Observer. The recruiting officer

was quite persuasive and before I left the hotel I had enlisted.

On 15 April 1942 I was called to Edmonton to start training

at RCAF No. 3 Manning Depot. I was assigned living quarters in a barracks

which housed about fifty airmen, and we slept in two-tier bunks. Except

for a few technicians we all started with the rank of AC2 [Aircraftsman

second class]. We were issued uniforms, mess kits, sewing kits called "housewives,"

brass button polishers, shoe shiners, and other gear. We received medical

and dental checkups. inoculations, physical training, marching drill, and

lessons in airmanship. Each airman made his own bed, polished his buttons,

badges and shoes and the entire group received periodic inspections. Everything

had to be kept neat and clean, strict discipline was enforced and every

man did his stint on guard duty.

When a group of about forty Australian airmen arrived

at the Manning Depot they decided to take in some Edmonton city night life,

even though they did not have permission to leave the base. They elected

to leave the base when I was on guard duty, and when I was near the farthest

end of my beat they made a hole in the fence big enough for a man to crawl

through. When I turned around at the end of my beat I saw a long lineup

of men in their dark blue Australian uniforms, in single file, crawling

hurriedly through the hole in the fence. I was carrying a .303 Enfield

rifle with fixed bayonet, but no ammunition was allowed for anyone on guard

duty. Being quite confident that I would not be able to stop these Australians,

I began running towards them, mostly running on the spot, waving my rifle

and shouting "Halt in the name of the King." They did not pay any attention

to me and when I arrived at the hole in the fence the last Australian was

a few feet too far away for me to reach him with the bayonet. Someone else

was on guard duty when the Australians returned [probably during the early

hours the next morning]. I heard no more about it so I presumed they got

back without incident.

During passes I would hop on my 1928 Harley Davidson motorcycle

and head for Wetaskiwin, where I spent most of the time building a Model

T Ford race car from parts at my father's auto wreckage. The category "Pilots

and Observers" was discontinued and all airmen in that category were remustered

to "Aircrew." This meant that any airman could be selected for training

as a pilot, navigator, bomb aimer, wireless air gunner or air gunner. On

19 July 1942, I was posted to No.7 Initial Training School at Saskatoon.

There were 42 airmen in Course #58 and we received classes and tests in

mathematics, wireless, navigation, meteorology, armament, anti-gas measures,

airmanship, drill, administration, and aircraft recognition. White cloth

flashes were placed in the front of our wedge caps to signify that we were

aircrew trainees. My Link trainer instructor was a Flying Officer Elder.

I passed the Link trainer portion of the course with the grade of 89 per

cent which, I was told, was the highest mark in the class. After the final

exams each graduate was interviewed individually by the selection committee

which, after considering the airman 's abilities, decided which members

of air crew should receive

training. I wanted to be a pilot and was pleased to be

selected for pilot training

All graduates of the course were promoted to LAC [Leading

Aircraftsman] and were given cloth propellers which were sewn on the sleeves

of their clothing to indicate their rank. Squadron Leader Fred McCall of

Calgary, the famous First World War ace, was one of the officials in the

picture when the class photograph was taken. Thirteen of the aircrew in

this class were killed on active service.

The graduates were authorized to have a pass the following

weekend in early October. The Model T Ford races were being held in Edmonton

on Thanksgiving day, 12 October. I had my car entered in the races, and

consequently I made an arrangement with the Station Warrant Officer by

which I would stay on the station the weekend of 3 October and would receive

my pass the following weekend. I was put to work in the station hospital

and spent the entire weekend doing undesirable jobs, mostly cleaning washrooms

and toilets. I did what I was told to do, I did a good job and I did not

complain about anything. When the following weekend arrived I was told

all passes were cancelled. Considering that it had taken nearly all of

my leave periods during the past five months to complete the assembly of

the race car, that it was painted with RCAF lettering and roundels on both

sides, that the Edmonton and other newspapers had published write-ups and

photographs promoting me and my car in the races, that I had been promised

leave to attend the races, and that I had already paid the consideration

by working the previous weekend in the hospital, I believed I was entitled

to leave to attend the races. When I left the station that weekend without

a pass I was considered to be AWL [away without leave].

I proudly raced my car and won second prize in the second

race. When I returned to Saskatoon, Squadon Leader Bawlf, the Chief

Ground Instructor, announced to other classes that I had gone AWL and was

therefore washed out of aircrew. I believe this announcement was to emphasize

to other students the consequences before they considered going AWL. As

I was now ground crew I was put to work in the camp kitchen where I washed

dishes, pots and pans, dished out meals in the mess hall, and scrubbed

tables and floors . Once again I did what I was told to do, I did a good

job and I did not complain about anything. After two weeks of kitchen duty

I was called into the office of Wing Commander Russell, the Commanding

Officer. He told me that I was being put back into aircrew and was being

sent to No. 6 Elementary Flying Training School at Prince Albert for pilot

training. It appeared he had received good reports of my work and discipline

while I was on kitchen duty; however, he never asked me why I had gone

AWL and I believe he never was fully aware of the reasons.

On 25 October I was posted to EFTS, where I was one of

45 students in Course #67. We were issued flying suits and other items

needed for our flying training and ground classes. My first flight in a

Tiger Moth biplane was on 28 October; my first solo flight was on 9 November,

after receiving eight hours and 45 minutes of dual-flying training. Most

of the flying instructors were civilians, and during flights they talked

to the students through speaking tubes called Gosports.

On 23 November I was given a 30-hour check by Ernie Boffa,

a well known bush pilot who was the Assistant Chief Flying Instructor.

During the test I was required to do various manoeuvres, including slow

rolls, blind flying [flying by instruments while under a hood], practice

forced landings, cross-wind landings, steep turns, tail spins, side

slipping, and other exercises. While practising aerobatics during a solo

flight on 28 November, an oil line ruptured and I flew back to base with

oil spraying on the windscreen. I flew 29 different Tiger Moths at EFTS;

my last flight there was on 18 December by which time I had logged 73 hours

and 25 minutes flying time on Tiger Moths. In my log book endorsement in

the space allocated for "Instructor's remarks on pupil's weakness" was

written "no particular faults." My flying grade was 74 per cent, and my

assessment was "above average." At least 14 pupils from Course 67 were

"washed out," which means their pilot training was terminated. Ten of the

students in this course were killed on active service overseas.

Pilot student Stan Reynolds

at No. 6 EFTS, Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, December1942.

The Tiger Moth is equipped with skis.

A Gosport hearing-tube needed for in-flight conversation

between instructor and student hangs from his helmet.

Photo courtesy Stanley G. Reynolds.

After completing my elementary training in December, I

went home on leave. A U.S. pilot flying a Bell Airacobra fighter experienced

engine trouble during a flight to Alaska, baled out and the plane crashed

nose first into the ground near Wetaskiwin. Personnel from the US air base

at Namao picked up all the parts they could locate, but they left the engine

which was buried about 17 feet down in the ground. I took it upon myself

to dig out the Allison V 12 engine, the 37 mm cannon that was buried under

the engine, live ammunition, propeller, and other gear. When I was digging

out the engine a spectator standing nearby threw a cigarette into the hole,

causing an explosion of the gas fumes. I came out of the hole so fast I

don't know whether I jumped out or was blown out. Not knowing of any useful

purpose for the articles, my father notified U.S. officials who sent an

army truck to pick up the remains of the Airacobra.

On 10 January 1943 I was posted to No.4 Service Flying

Training School at Saskatoon, where I was placed in Course #72 with 61

other student pilots. We were learning to fly twin-engine Cessna Cranes,

and my flying instructor was Pilot Officer Macintyre. My first solo in

a Crane was on 24 January, after receiving eight hours and 40 minutes dual-training.

During a solo flight on 7 April the fuel pump quit in the starboard engine.

I flew back to base on one engine and made a successful single engine landing.

My last flight in a Crane was 22 April, by which date I had logged 166

hours and 40 minutes twin-engine day-and-night flying time. By then I also

had logged 35 hours in the Link trainer, not including my Link time at

ITS. At least 14 pupils in Course 72 were washed out. Not every pilot received

his wings on the parade square. A day or two before this important occasion

I was stricken with appendicitis and taken to the base hospital where I

received an appendectomy.

As I was not allowed to leave the hospital bed, my pilot

wings were pinned on my pyjamas by an officiating officer from high command.

In attendance were my instructor, other graduating pilots from my course,

the doctor and nurse, various officials from the base and my very proud

father. This was one of the most thrilling experiences in my air force

career. I had graduated from SFTS flying twin-engine Cessna Cranes, and

was now a full-fledged pilot. In my log book endorsement in the space allocated

for "Instructors remarks on pupil's weakness" was written "High average

student, should do well in all future flying." I was promoted to the rank

of Sergeant. Fifteen of the students in this class were killed - on active

service overseas.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Stan Reynolds

was a legend in the museum and aviation community in Canada. After his

Royal Canadian Air Force Service in World War II, Stan returned to his

home in Wetaskiwin Alberta and grew a very successful automobile and farm

machinery business. His words in the story indicate that he acquired the

'collector bug' early in his life. He amassed a huge collection of vintage

automobiles, motorcycles, bicycles, trucks, stationary engines, tractors,

agricultural implements, aircraft and industrial equipment of which 1500

items were donated as a start to the Reynolds-Alberta museum in Wetaskiwin

Alberta. Among other honours, he was inducted in the Aviation Hall of Fame

in 2009 and named to the Order of Canada in 1999.

Reynolds died in February of 2012 at the age of 88

years and his wife Hallie, passed away in August 2012 at the age of 85

years.

029 of

150

BCATP A World War II Memory: Stan Reynolds - Pilot

- Part 2 of 3

Part 2 – Training Overseas in a OTU (Operational

Training Unit)

I went home on embarkation leave prior to leaving for

overseas. I boarded a train with other airmen, and arrived at No.1 "Y"

Depot, Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 21 June. A few days later we boarded the

troop ship "Louis Pasteur," joined a convoy and headed for England. The

ships travelled in a zig-zag path to lessen the chances of being hit by

a torpedo from an enemy submarine. We were told that some submarines were

picked up in the ships sonar, although no ships were torpedoed in this

convoy.

On Dominion Day I was posted with other pilots to No.

3 Personnel Receiving Centre at Bournemouth, on the south coast of England.

This city had been the target of a low-level attack by enemy aircraft and

a number of buildings showed mute evidence of the strafing and bombing.

At Bournemouth we were given training in parachute-harness releasing over

land and water, use of the life preservers called "Mae Wests," jumping

into a pool of water from a high platform, and lots of physical exercise

which included routinely swimming several lengths of the swimming pool.

We also received instruction on the use of firearms, and did target practice

with revolvers. As part of our emergency kit, our photographs were taken

in civilian clothes, to be used by the underground for forged passports

if we were forced down in enemy territory.

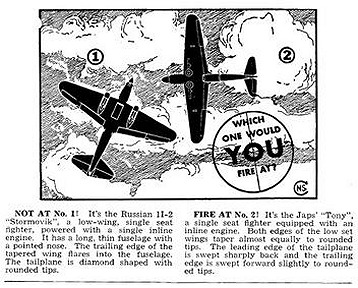

We received training and tests on wireless, aircraft recognition,

link theory, armament, ship recognition, and naval theory. On 26 and 27

August, at the Empire Central Flying School at Hullavington, I took flight

tests in a Miles Master and an Airspeed Oxford. From Bournemouth the pilots

were posted to various bases for further flight training, depending upon

their qualifications and capabilities. I was fortunate to have good night

vision, good aircraft recognition and my ability as a pilot was satisfactory

so it was decided my further flying training should be as a night fighter

pilot.

LAC Stan Reynolds readies himself for a solo flight

in a Cessna Crane at No. 4 SFTS, Saskatoon, during April 1943.

Note the quick release fastener at the front of

the parachute harness and the ripcord on his left side.

Photo courtesy Stanley G. Reynolds.

On 22 September I was posted to No. 12 Advanced Flying

Unit at Grantham, Lincolnshire, where I was one of 51 pilots in Course

#17. In this course were servicemen from around the world: 33 RAF, six

RCAF, four RAAF [Royal Australian Air Force], two RNZAF [Royal New Zealand

Air Force], two SAAF [South African Air Force], an airman from Pol and

one from Java, one from Scotland one from USA. One of the pilots in this

course was S/L George Edwards, who was the Chief Flying Instructor during

the time I was training at No. 4 SFTS Saskatoon. We were flying twin-engine

Bristol Blenheim Mark Vs, known in England as 'Bisleys.' I received 4 ½

hours dual-instruction before my first solo flight on 8 October, and was

promoted to Flight Sergeant on 30 October.

Shortly before Christmas a group of about half a dozen

airmen in my barrack block got together to play carols using a group of

bottles partially filled with water. Each bottle was filled to a different

level to produce a different musical note when an airman blew over the

top of the bottle. Each of us controlled several bottles and after hours

of practice we became quite proficient in playing "Good King Wenceslas."

During a solo cross-country flight on 24 February 1944,

the ceiling, 10/10th overcast, came down and I was forced down to under

300 feet to fly below the low ceiling. Endeavouring to map read at such

a low height while flying over territory containing numerous roads and

railways crisscrossing and running all directions, often having to read

the aircraft instruments and look ahead for obstructions, I became lost.

I flew with 15 degrees of flap to maintain safe control at a slower speed,

but I was unable to pinpoint my location on the map. I still had a reasonable

fuel supply when I flew over an air base where the planes were all grounded

because of the bad weather. I made a quick circuit, landed and taxied up

to the control tower. The control officer said that if I shut off the engines

I would have to stay. Therefore I left the engines idling at 1000 rpm,

set the brakes, and walked into the control tower where I was told I had

landed at Polebrook, a United States Air Force base. I drew a line on my

map from Polebrook to Grantham, took off and map-read my way back to my

base, landed and parked the plane in its proper place. When I landed at

Grantham I was over two hours late; however nobody asked me why I was overdue.

Flying Officer Osborne, RAF, was one of the pilots killed during the flying

training of Course #17.

Ground school classes were Morse code wireless, navigation,

meteorology, aircraft recognition, armament, and engines. During a pass

I went to London and spent the night at a servicemen's hostel at Earls

Court. That night the air raid sirens began wailing and the German planes

dropped their bombs. Instead of going to an air raid shelter as most cautious

people would do, I stayed in my room which was on an upper floor. I could

not quite muster the urge to leave the hostel bed and traverse four flights

of stairs for a sojourn in a bomb shelter. Next morning I looked out the

window and noticed that the street was barricaded. A large bomb had dropped

in the street in front of the building but had failed to explode. Being

a born collector I picked up from the streets of London about twenty pieces

of shrapnel which I still have.

On 29 February I was posted to No. 51 Operational Training

Unit at Cranfield, Buckinghamshire. Here we had to learn to fly twin-engine

Bristol Beaufighters, an airplane which had a gross weight of over twelve

tons, and a top speed of over 300 mph. This was a plane on which we could

not receive dual instruction because it had only one front seat and no

provision for a second pilot. I was in Course #31 which had 25 pilots and

24 radio navigators. Six of the pilots held the rank of Flight Lieutenant

or higher. One of the pilots was a Technical Sergeant in the United States

Army Air Corps. An RAF Sergeant, who was not a member of aircrew, gave

each pilot instruction while he was sitting in the pilot's seat of a Beaufighter

cockpit section called a "dummy fuselage." We had to learn the readings

and all the operations of the instruments, gauges, switches, controls,

and radio. We had to be proficient in going through the sequences of operations

needed by a pilot during takeoff, climb, flight, gliding, and landing.

This would include adjustment of the propellers, engine coolers, retracting

the landing gear, operation of the flaps, and radio operation.

When the ground instructor was satisfied that the pilot

knew what to do in the cockpit, he would approve the pilot to fly the Beaufighter.

I received nine hours and 40 minutes dual day-and-night flying, and instrument

flying in a Bristol Beaufort. On 19 March I made my first solo flight in

a Beaufighter. After 5 ½ hours of solo flying I was assigned a radio-navigator,

Sergeant Donald MacNicol from Winnipeg. The call sign allocated to me was

"Jungle three niner," used mostly during radio communications. During time

off we often chummed around with another crew in the same course, Sergeant

Robert S. Walker, a pilot, and Sergeant George R. Fawcett, his radio-navigator.

During a landing on 23 April the port tire blew out and the drag was too

great to keep the Beaufighter on the runway. The wheel tore a deep groove

in the sod, although the plane was undamaged. There was another pilot coming

in to land behind me, and after I got stopped I heard his voice on the

radio saying "good show three niner!"

During a night flight in April I was flying near London

when several flights of German aircraft began dropping bombs. I could see

the German planes coned in the searchlights with numerous anti-aircraft

shells exploding around them. There was nothing I could do because on training

flights we carried no ammunition for the guns. During night flights we

were directed by ground control which gave us messages by radio. The Germans

had jammed our radio frequencies during the raid so I could not be vectored

back to base. Also the lights were shut off at the airfields to prevent

them from becoming a target, so I was unable to land during the raid. After

the raid was over and the radio jamming was lifted I was directed back

to my base. On 30 April, after 32 hours and 55 minutes day-and-night flying

training in a Mark I Beaufighter plus numerous hours in ground classes

I finished my course at No. 51 OTU.

030 of

150

BCATP A World War II Memory: Stan Reynolds - Pilot

- Part 3 of 3

Part 3 - Aircraft Operations Overseas

On 1 May Don MacNicol and I were posted to RAF Station

Winfield on the east coast of Scotland. We were the only RCAF crew in "A"

Flight. All the rest of the fifteen crews were RAF. Robert Walker and George

Fawcett also were posted to Winfield and were one of sixteen crews in "B"

Flight. From this base most of our flights were over the North Sea in Mark

VI Beaufighters, with two Bristol Hercules 1650 horsepower engines, four

20 mm cannons, six .303 machine guns and radar in the nose. We flew Mark

II Beaufighters with Rolls

F/S Stan Reynolds wearing "battle dress"

beside his Mark II Beaufighter

at RAF Station Winfield, Scotland in May 1944.

A radar antenna is fastened to the port wing behind him.

Photo courtesy Stanley G. Reynolds.

Royce Merlin engines during air-to-ground firing, and

when firing at target drogues being pulled by Fairey Battles. One of the

first things we noticed was the number of WAAF [Women's Auxiliary Air Force]

working on airplane engines. With my folding camera, which I could carry

in my pocket, I took some photographs of these women at work. On 6 June

1944 [D-Day ], the supercharger in the starboard engine was unserviceable

so we flew back to base after a short flight. We were not informed about

the invasion until the next day.

On 11 June we flew back to base after a short flight for

the reason "weapons bent," meaning our guns wouldn't fire. Quite often

the night flying aircrew received carrots with their meals as the vitamins

in carrots were said to be of benefit to our night vision. Everyone had

brussels sprouts with most meals, and periodically a chicken egg was al

located to each flyer. We had to stand in a single-file queue, and when

we got to the front of the line we signed our name on a dotted line to

receive our single egg. Each airman took his own egg to the mess kitchen

and told the cook how he wanted it cooked; we would then eat the egg with

the rest of the meal that was dished out to us. Don MacNicol received comfort

parcels from home which contained cans of Spork, Spam, jam, peanut butter,

and margarine. He would take a can of jam or peanut butter to the mess

hall and put it on the table in front of us. After a few minutes RAF ground

crew would come over to our table with a slice of bread in their hand and

meekly ask if they could have a little bit of the jam or peanut butter.

Don never refused anyone, and soon the can was empty.

My twenty-first birthday was on 17 May, and on this day

I spent an hour and ten minutes flying a Mark II Beaufighter, firing 20

mm cannons at a target drogue being pulled by a Fairey Battle. Don became

quite friendly with Robert Walker, and asked if I would mind if he crewed

up with Walker, in which event George Fawcett would become my R/N [radio

navigator]. George and I had no objection, so MacNicol became Walker's

R/N and Fawcett became my R/N.

Late at night on 19 June George and I were "scrambled"

[took off] and vectored to intercept two "bogies" [enemyaircraft] flying

high over the North Sea towards Edinburgh. We had climbed to 16,000 feet

when the bogies had completed their reconnaissance mission and were heading

back towards Norway. During their flight they descended, at the same time

giving them a greater speed. Because we were on an interception course

we were able to get fairly close to one of the bogies, but not close enough

to be able to see the plane visually, which would enable us to fire our

guns. When our height was down to about 100 feet above the North Sea waves,

we had to level out and the German planes, being faster than our Beaufighter,

pulled away from us. Later we were told that they were probably Messerschmitt

21 Os based in Norway. On 21 June, after 31 day-and-night flights in Beaufighters,

I was posted with my R/N to 410 Cougar Squadron RCAF based at Zeals, Wiltshire.

At this time 410 Squadron was assigned to the Defence

of Britain. It was a night fighter squadron equipped with Mark XIII and

Mark XXX DeHavilland Mosquitoes fitted with four Hispano Suiza 20 mm cannons

in the belly and radar equipment in the nose. They had two Rolls Royce

Merlin 1650 horsepower engines, and a top speed of 420 miles per hour.

There were instruments, gauges and controls on both sides as well as in

the front of the cockpit, and the radio had 32 channels. There also was

one Mark III Mosquito that had dual controls. On 23 June, with F/0 Edwards

at the controls and me in the other seat, he flew one circuit, then told

me to fly a circuit. After I landed he told me to continue flying circuits

and left me alone in the plane. I took off on my first solo flight in a

Mosquito, and practised takeoffs and landings for an hour and 25 minutes.

I thought to myself at the time how much nicer and easier it was to fly

the Mosquito than the Beaufighter.

We were using a grass airfield without runways, smaller

than most other bases. We slept in tents on folding cots at that time.

When we took a shower we used a hand-pumper fire extinguisher filled with

water, and took turns spraying water on each other. W/C Abner Hiltz was

our Commanding Officer, and George Fawcett and I were one of sixteen crews

in "B" Flight. S/L J.D. "Red" Somerville was our Flight Commander, and

F/L Walter Dinsdale was the Assistant Flight Commander.

During a night flight in a Mark XIII Mosquito on 9 July,

the starboard engine burst into flame. I shut off the fuel line and switches

for this engine, feathered the propeller and activated the fire extinguisher

which put out the fire. I flew back to base on one engine, aniving about

2:30AM. When a twin-engine airplane flying on one engine slows below a

certain air speed, there is not enough rudder control to keep the aircraft

in a safe attitude if too much power is used on the operating engine. The

increased pull from the operating engine causes the plane to become uncontrollable

and crash. Consequently pilots are trained to approach the landing field

at a greater height than is usual; if there is an overshoot or undershoot

during landing, it is safer to hit the far fence at a slower speed than

it is to hit the near fence at flying speed.

When I was certain I would reach the landing field, I

activated the flap and undercarriage controls. There is a hydraulic pump

on each engine; as one engine was inoperative the hydraulic pump connected

to that engine was not working. The hydraulic pressure from the single

pump operated the flaps and undercarriage so slowly that they were only

partially down, and I could not get the plane stopped before I ran out

of landing space. As soon as I was aware that the plane was not slowing

down fast enough and the undercarriage was only part way down, I returned

the landing gear control to the retract position and the plane skidded

on its belly into a coulee adjacent to the landing field.

RCAF 410 Squadron Mosquito night Fighters

stationed at Colerne, Wiltshire, in August 1944.

Black and white striping was painted on the underside

of the aircraft shortly before D-Day.

Facial scars on pilot Stan Reynolds resulted from crash landing

his partially disabled Mosquito during a night flight in July 1944.

Photo courtesy Stanley G. Reynolds.

The plane could not be stopped while it was skidding down

the slope on the near side of the coulee; however, it came to a sudden

stop when it went across a small creek and hit the bottom of the ascending

slope on the other side. My head hit the instrument panel and I received

facial lacerations while George's jaw was broken. The port engine caught

fire, and in order to save time I disconnected my parachute and threw off

my helmet with earphones and oxygen mask, rather than disconnect them.

When I attempted to leave the plane I found my left foot was caught under

the damaged rudder bar. After twisting around and spraining my ankle in

the process, my foot became dislodged. By this time the fire was burning

up the left side of the fuselage singeing the left side of my clothing

and the hair on the left side of my head.

We crawled out a hole on the right side of the fuselage,

and while we were crawling away on our hands and knees the port fuel tanks

exploded. A few seconds later the ammunition also started exploding. After

we had crawled about 100 yards away we sat on the ground getting our bearings

and watching the burning plane. After another ten minutes we got up on

our feet, I put one arm over George's shoulders to take some of the weight

off my sprained ankle, and we walked about a quarter mile to a house. George

knocked on the door and an elderly lady in her night gown opened the door.

She was quite startled when she saw us with blood running down our faces

and the front of our uniforms. She let us in the house and after we told

her what happened she telephoned the base and a short time later we were

picked up by an ambulance-hearse, and taken to the base hospital.

Lacking any anaesthetic, the doctor stitched the lacerations

in my face without benefit of painkillers. Later we were strapped on stretchers

in an Oxford ambulance plane piloted by F/0 Snowden. With F!L Rogers, the

Medical Officer, in attendance, we were taken to Gatwick airport. From

Gatwick we were taken to the Queen Victoria Hospital at East Grinstead,

Sussex. Soon after we were placed in hospital beds and official photographs

were taken of our head wounds for the hospital records. I was visited by

Wing Commander Ross Tilley, the doctor in charge of the Canadian wing of

the hospital. He took a quick look at me, ripped the scabs off my face,

talked to me for a few minutes, then left to attend other airmen whose

injuries were more severe than mine. Many of the patients were burn victims

and were receiving plastic surgery from Dr. Tilley. Because this type of

surgery was in its infancy, and was somewhat experimental, these patients

became known as Guinea Pigs. A Club was formed and all patients who were

in the Queen Victoria Hospital became official members of the Guinea Pig

Club.

German V1 flying bombs, called "buzz bombs" or "doodlebugs,"

flew over quite often on their way from France to London. During my recovery

at the Queen Victoria hospital the patients were visited by an entertainment

group from the Women's Division of the RCAF, called the "All Clear" .group.

The lady in charge was Flight Officer Alice Fahrenholtz, who later married

Brigadier General William F. Newson, a member of Canada's Aviation Hall

of Fame. Some of the airmen who were not confined to their beds were honoured

by having their photograph taken with the young ladies. I was one of six

airmen who had their picture taken with four smiling ladies in their RCAF

uniforms; the pretty redhead wi th her hand resting on my left shoulder

was LAW [Leading Airwoman] Maureen Harrington from Edmonton. When I left

the hospital to return to the squadron I was picked up by F/0 Sexsmith

in an Airspeed Oxford. He was accompanied by W/0 Jones and W/0 Gregory,

who slept in the same tent as George and I. George was not released from

the hospital until later because his jaw had not yet healed.

On 5 August I was given a fli ght test in an Oxford by

F/0 Green, to check that the accident had not affected my flying ability.

On 8 August, being anxious to get back into the air, I took the Squadron

utility airplane, a Miles Magister, for an hour's flight. Many of the ground

crew wanted to get into the air whenever they had a chance,so I took LAC

Coffin. from Edmonton, as my passenger on this flight. On 11 August I was

back fl ying a Mark XIII Mosquito, and made three flights that day. In

August the squadron was moved from Zeals to Colerne, Wiltshire, an airfield

with paved runways. We were given RCAF Form R60, which was a Will, and

were urged to complete it. On 16 August 1 completed my Will, and another

air crew signed as witnesses. These were F/L Ben E. Plumer, pilot, from

Bassano, Alberta and his N/R F/0 Evans.

F/S Stan Reynolds in the cockpit of

a Mosquito Mark XXX Night Fighter in August 1944.

Photo courtesy Stanley G. Reynolds.

I flew a number of practice intercepts in which my Mossie

was the target and a crew in another Mossie would track me with their radar

and endeavour to catch or intercept me. During these exercises, both aircraft

carried loaded guns in the event either one or both planes were diverted

to intercept a bandit or buzz bomb. After 35 day-and-night flights in Mosquitoes,

I flew a Magister to an airport near London. From there I was sent to the

Repatriation Depot at Manchester, and received a promotion to Warrant Officer

second class effective 30 April. On 10 October my first RIN Don MacNicol

was killed while he was serving with 406 Mosquito night-fighter squadron.

On 14 October I was awarded a Wound Stripe for injuries received on active

service, and on 30 October was promoted to WO 1 [Warrant Officer first

class]. I left Manchester on the ocean liner Queen Elizabeth, which was

filled with troops, and several days later docked in New York harbour.

From there I travelled to eastern Canada, and then back to Alberta by train.

I was very disappointed when I was discharged in 1945,

as I liked to fly and would have been happy to stay in the air force as

a pilot. In January 1947 I received a letter from No.2 Air Command, RCAF

Winnipeg, stating that a Mosquito Squadron was to be formed for overseas

service, and offering ·me a five-year commission with the rank of

Flight Lieutenant. Later it was learned that this squadron was sent to

China where the Canadians taught Nationalist Chinese to fly and maintain

Mosquitos obtained in Canada for use against the Communists. By this date

I had built a garage, owned a car sales lot and had a business that was

progressing successfully. I therefore did not go back into the air force;

however, if I had done so it is probable that my future would have been

significantly different.

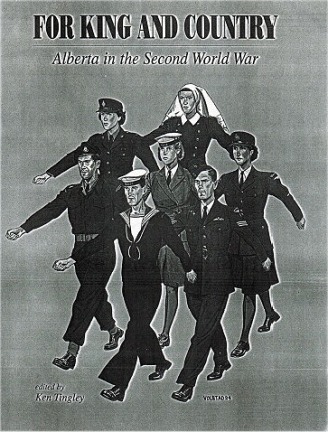

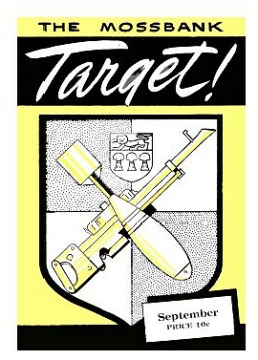

Always

it is the right spirit that counts: "Esprit do Corps", it is called in

the Service. It is no secret that the Spirit of Mossbank is the right spirit

andúthat which has made it possible for you to retain first place

in the awarding of the Minister for Air's Efficiency Pennant. You, each

one of you -Officer, N.C.O., airmam, airwoman and civilian alike -

Always

it is the right spirit that counts: "Esprit do Corps", it is called in

the Service. It is no secret that the Spirit of Mossbank is the right spirit

andúthat which has made it possible for you to retain first place

in the awarding of the Minister for Air's Efficiency Pennant. You, each

one of you -Officer, N.C.O., airmam, airwoman and civilian alike -

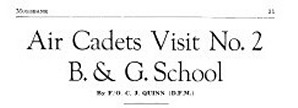

This

year No. 2 B.&G. School once more became the host of Cadets from the

surrounding district, and Calgary. There were two camps held, the first

from July 4th to July 14th. It was comprised of squadrons from Assiniboia,

Tugaske, Wilcox and Gravelbourg. The second camp was from July 18th to

July 28th, and was made up of only one squadron from Calgary.

This

year No. 2 B.&G. School once more became the host of Cadets from the

surrounding district, and Calgary. There were two camps held, the first

from July 4th to July 14th. It was comprised of squadrons from Assiniboia,

Tugaske, Wilcox and Gravelbourg. The second camp was from July 18th to

July 28th, and was made up of only one squadron from Calgary.

In

December 2000, the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum received this

air force history from Stan Reynolds. It is one chapter out of a book commissioned

by the Alberta Department of Culture commemorating the 50th anniversary

of the end of hostilities in World War II. The book is "For King and Country

– Albertans in the Second World War" and Stan’s chapter was in the Albertans

Overseas section.

In

December 2000, the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum received this

air force history from Stan Reynolds. It is one chapter out of a book commissioned

by the Alberta Department of Culture commemorating the 50th anniversary

of the end of hostilities in World War II. The book is "For King and Country

– Albertans in the Second World War" and Stan’s chapter was in the Albertans

Overseas section.

The

Reynolds family of Wetaskiwin has always been interested in aviation. My

father, Edward A [Ted] Reynolds, was a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps

during the First World War. My older brother, Byron E. [Bud] Reynolds,

joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940, and completed a Tour of Operations

as a flight engineer on Catalina flying boats. My younger brother, Allan

B. [Bert] Reynolds, joined the RCAF in 1943, and served overseas as an

air-frame mechanic on Dakotas [C-47s] with 437 Squadron. When I was sixteen

years old I joined the Edmonton Fusiliers and trained with E Company at

Wetaskiwin during periods that did not conflict with school hours. The

two weeks' training at Sarcee Camp in Calgary during the summer months

was a great experience, with sleeping in tents and target practice with

Ross rifles. In 1941 I was hired as a truck driver for MacGregor Telephone

& Power Construction Co. of Edmonton during the time they were installing

power lines at the RCAF stations at High River, Claresholm, De Winton,

and other locations.

The

Reynolds family of Wetaskiwin has always been interested in aviation. My

father, Edward A [Ted] Reynolds, was a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps

during the First World War. My older brother, Byron E. [Bud] Reynolds,

joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940, and completed a Tour of Operations

as a flight engineer on Catalina flying boats. My younger brother, Allan

B. [Bert] Reynolds, joined the RCAF in 1943, and served overseas as an

air-frame mechanic on Dakotas [C-47s] with 437 Squadron. When I was sixteen

years old I joined the Edmonton Fusiliers and trained with E Company at

Wetaskiwin during periods that did not conflict with school hours. The

two weeks' training at Sarcee Camp in Calgary during the summer months

was a great experience, with sleeping in tents and target practice with

Ross rifles. In 1941 I was hired as a truck driver for MacGregor Telephone

& Power Construction Co. of Edmonton during the time they were installing

power lines at the RCAF stations at High River, Claresholm, De Winton,

and other locations.