Bill Hillman's Monthly Military Tribute

AS YOU WERE . . .

WAR YEARS ECLECTICA

2017.04 Edition

Click for larger full-screen images

UNFORGETTABLE IMAGES OF

WAR, CONFLICT . . . and LIFE

Award-winning photos captured by LIFE Magazine Photographers

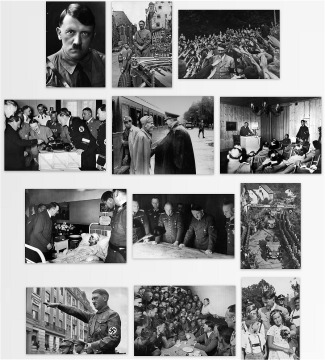

Click for full-screen imagesSpectacle was like oxygen for the Nazis, and Heinrich Hoffmann was instrumental in staging Hitler’s growing pageant of power. Hoffmann, who joined the party in 1920 and became Hitler’s personal photographer and confidant, was charged with choreographing the regime’s propaganda carnivals and selling them to a wounded German public. Nowhere did Hoffmann do it better than on September 30, 1934, in his rigidly symmetrical photo at the Bückeberg Harvest Festival, where the Mephistophelian Führer swaggers at the center of a grand Wagnerian fantasy of adoring and heiling troops. By capturing this and so many other extravaganzas, Hoffmann—who took more than 2 million photos of his boss—fed the regime’s vast propaganda machine and spread its demonic dream.

Hitler at a Nazi Party Rally ~ 1934 and More.

Such images were all-pervasive in Hitler’s Reich, which shrewdly used Hoffman’s photos, the stark graphics on Nazi banners and the films of Leni Riefenstahl to make Aryanism seem worthy of godlike worship. Humiliated by World War I, punishing reparations and the Great Depression, a nation eager to reclaim its sense of self was rallied by Hitler’s visage and his seemingly invincible men aching to right wrongs. Hoffmann’s expertly rendered propaganda is a testament to photography’s power to move nations and plunge a world into war.

Britain stood alone in 1941. By then Poland, France and large parts of Europe had fallen to the Nazi forces, and it was only the tiny nation’s pilots, soldiers and sailors, along with those of the Commonwealth, who kept the darkness at bay. Winston Churchill was determined that the light of England would continue to shine. In December 1941, soon after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and America was pulled into the war, Churchill visited Parliament in Ottawa to thank Canada and the Allies for their help. Churchill wasn’t aware that Yousuf Karsh had been tasked to take his portrait afterward, and when he came out and saw the Turkish-born Canadian photographer, he demanded to know, “Why was I not told?” Churchill then lit a cigar, puffed at it and said to the photographer, “You may take one.”

Winston Churchill ~ 1941As Karsh prepared, Churchill refused to put down the cigar. So once Karsh made sure all was ready, he walked over to the Prime Minister and said, “Forgive me, sir,” and plucked the cigar out of Churchill’s mouth. “By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent, he could have devoured me. It was at that instant that I took the photograph.” Ever the diplomat, Churchill then smiled and said, “You may take another one” and shook Karsh’s hand, telling him, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed.”

The result of Karsh’s lion taming is one of the most widely reproduced images in history and a watershed in the art of political portraiture. It was Karsh’s picture of the bulldoggish Churchill—published first in the American daily PM and eventually on the cover of LIFE—that gave modern photographers permission to make honest, even critical portrayals of our leaders.

The terrified young boy with his hands raised at the center of this image was one of nearly half a million Jews packed into the Warsaw ghetto, a neighborhood transformed by the Nazis into a walled compound of grinding starvation and death. Beginning in July 1942, the German occupiers started shipping some 5,000 Warsaw inhabitants a day to concentration camps. As news of exterminations seeped back, the ghetto’s residents formed a resistance group. “We saw ourselves as a Jewish underground whose fate was a tragic one,” wrote its young leader Mordecai Anielewicz. “For our hour had come without any sign of hope or rescue.”

Jewish Boy Surrenders in Warsaw ~ 1943That hour arrived on April 19, 1943, when Nazi troops came to take the rest of the Jews away. The sparsely armed partisans fought back but were eventually subdued by German tanks and flamethrowers. When the revolt ended on May 16, the 56,000 survivors faced summary execution or deportation to concentration and slave-labor camps. SS Major General Jürgen Stroop took such pride in his work clearing out the ghetto that he created the Stroop Report, a leather-bound victory album whose 75 pages include a laundry list of boastful spoils, reports of daily killings and dozens of heart-wrenching photos like that of the boy raising his hands.

This collection proved his undoing, for besides giving a face to those who died, the pictures reveal the power of photography as a documentary tool. At the subsequent Nuremburg war-crimes trials, the volume became key evidence against Stroop and resulted in his hanging near the ghetto in 1951. The Holocaust produced scores of searing images. But none had the evidentiary impact of the boy’s surrender. The child, whose identity has never been confirmed, has come to represent the face of the 6 million defenseless Jews killed by the Nazis.

Helen of Troy, the mythic Greek demigod who sparked the Trojan War and “launch’d a thousand ships,” had nothing on Betty Grable of St. Louis. For that platinum blond, blue-eyed Hollywood starlet had a set of gams that inspired American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines to set forth to save civilization from the Axis powers. And unlike Helen, Betty represented the flesh-and-blood “girl back home,” patiently keeping the fires burning. Frank Powolny brought Betty to the troops by accident.

Betty Grable ~ 1943A photographer for 20th Century Fox, he was taking publicity pictures of the actress for the 1943 film Sweet Rosie O’Grady when she agreed to a “back shot.” The studio turned the coy pose into one of the earliest pinups, and soon troops were requesting 50,000 copies every month. The men took Betty wherever they went, tacking her poster to barrack walls, painting her on bomber fuselages and fastening 2-by-3 prints of her next to their hearts. Before Marilyn Monroe, Betty’s smile and legs—said to be insured for a million bucks with Lloyd’s of London—rallied countless homesick young men in the fight of their lives (including a young Hugh Hefner, who cited her as an inspiration for Playboy). “I’ve got to be an enlisted man’s girl,” said Grable, who signed hundreds of her pinups each month during the war. “Just like this has got to be an enlisted man’s war.”

It is but a speck of an island 760 miles south of Tokyo, a volcanic pile that blocked the Allies’ march toward Japan. The Americans needed Iwo Jima as an air base, but the Japanese had dug in. U.S. troops landed on February 19, 1945, beginning a month of fighting that claimed the lives of 6,800 Americans and 21,000 Japanese. On the fifth day of battle, the Marines captured Mount Suribachi. An American flag was quickly raised, but a commander called for a bigger one, in part to inspire his men and demoralize his opponents.

Flag Raising on Iwo Jima ~ 1945Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal lugged his bulky Speed Graphic camera to the top, and as five Marines and a Navy corpsman prepared to hoist the Stars and Stripes, Rosenthal stepped back to get a better frame—and almost missed the shot. “The sky was overcast,” he later wrote of what has become one of the most recognizable images of war. “The wind just whipped the flag out over the heads of the group, and at their feet the disrupted terrain and the broken stalks of the shrubbery exemplified the turbulence of war.” Two days later Rosenthal’s photo was splashed on front pages across the U.S., where it was quickly embraced as a symbol of unity in the long-fought war. The picture, which earned Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize, so resonated that it was made into a postage stamp and cast as a 100-ton bronze memorial.

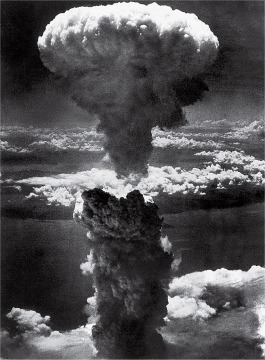

Three days after an atomic bomb nicknamed Little Boy obliterated Hiroshima, Japan, U.S. forces dropped an even more powerful weapon dubbed Fat Man on Nagasaki. The explosion shot up a 45,000-foot-high column of radioactive dust and debris. “We saw this big plume climbing up, up into the sky,” recalled Lieutenant Charles Levy, the bombardier, who was knocked over by the blow from the 20-kiloton weapon. “It was purple, red, white, all colors—something like boiling coffee. It looked alive.” The officer then shot 16 photographs of the new weapon’s awful power as it yanked the life out of some 80,000 people in the city on the Urakami River.

Mushroom Cloud Over Nagasaki ~ 1945Six days later, the two bombs forced Emperor Hirohito to announce Japan’s unconditional surrender in World War II. Officials censored photos of the bomb’s devastation, but Levy’s image—the only one to show the full scale of the mushroom cloud from the air—was circulated widely. The effect shaped American opinion in favor of the nuclear bomb, leading the nation to celebrate the atomic age and proving, yet again, that history is written by the victors.

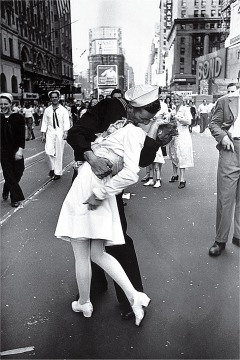

At its best, photography captures fleeting snippets that crystallize the hope, anguish, wonder and joy of life. Alfred Eisenstaedt, one of the first four photographers hired by LIFE magazine, made it his mission “to find and catch the storytelling moment.” He didn’t have to go far for it when World War II ended on August 14, 1945. Taking in the mood on the streets of New York City, Eisenstaedt soon found himself in the joyous tumult of Times Square.

V-J Day in Times Square ~ 1945As he searched for subjects, a sailor in front of him grabbed hold of a nurse, tilted her back and kissed her. Eisenstaedt’s photograph of that passionate swoop distilled the relief and promise of that momentous day in a single moment of unbridled joy (although some argue today that it should be seen as a case of sexual assault). His beautiful image has become the most famous and frequently reproduced picture of the 20th century, and it forms the basis of our collective memory of that transformative moment in world history. “People tell me that when I’m in heaven,” Eisenstaedt said, “they will remember this picture.”

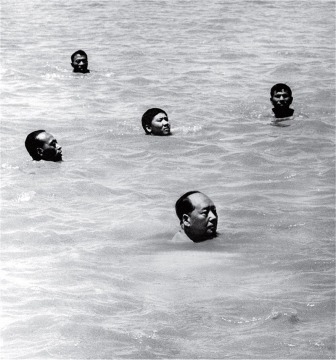

After decades leading the Chinese Communist Party and then his nation, Mao Zedong began to worry about how he would be remembered. The 72-year-old Chairman feared too that his legacy would be undermined by the stirrings of a counterrevolution. And so in July 1966, with an eye toward securing his grip on power, Mao took a dip in the Yangtze River to show the world that he was still in robust health. It was a propaganda coup.

Chairman Mao Swims in the Yangtze ~ 1966The image of that swim, one of the few widely circulated photos of the leader, did just what Mao hoped. Back in Beijing, Mao launched his Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, rallying the masses to purge his rivals. His grip on power was tighter than ever. Mao enlisted the nation’s young people and implored these rabid Red Guards to “dare to be violent.” Insanity quickly descended on the land of 750 million, as troops clutching the Chairman’s Little Red Book smashed relics and temples and punished perceived traitors. When the Cultural Revolution finally petered out a decade later, more than a million people had perished.

In June 1963, most Americans couldn’t find Vietnam on a map. But there was no forgetting that war-torn Southeast Asian nation after Associated Press photographer Malcolm Browne captured the image of Thich Quang Duc immolating himself on a Saigon street. Browne had been given a heads-up that something was going to happen to protest the treatment of Buddhists by the regime of President Ngo Dinh Diem. Once there he watched as two monks doused the seated elderly man with gasoline. “I realized at that moment exactly what was happening, and began to take pictures a few seconds apart,” he wrote soon after.

The Burning Monk ~ 1963His Pulitzer Prize–winning photo of the seemingly serene monk sitting lotus style as he is enveloped in flames became the first iconic image to emerge from a quagmire that would soon pull in America. Quang Duc’s act of martyrdom became a sign of the volatility of his nation, and President Kennedy later commented, “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.” Browne’s photo forced people to question the U.S.’s association with Diem’s government, and soon resulted in the Administration’s decision not to interfere with a coup that November.

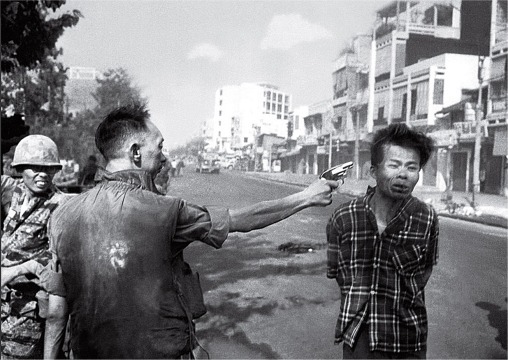

The act was stunning in its casualness. Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams was on the streets of Saigon on February 1, 1968, two days after the forces of the People’s Army of Vietnam and the Viet Cong set off the Tet offensive and swarmed into dozens of South Vietnamese cities. As Adams photographed the turmoil, he came upon Brigadier General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, chief of the national police, standing alongside Nguyen Van Lem, the captain of a terrorist squad who had just killed the family of one of Loan’s friends. Adams thought he was watching the interrogation of a bound prisoner. But as he looked through his viewfinder, Loan calmly raised his .38-caliber pistol and summarily fired a bullet through Lem’s head.

Saigon Execution ~ 1968After shooting the suspect, the general justified the suddenness of his actions by saying, “If you hesitate, if you didn’t do your duty, the men won’t follow you.” The Tet offensive raged into March. Yet while U.S. forces beat back the communists, press reports of the anarchy convinced Americans that the war was unwinnable. The freezing of the moment of Lem’s death symbolized for many the brutality over there, and the picture’s widespread publication helped galvanize growing sentiment in America about the futility of the fight. More important, Adams’ photo ushered in a more intimate level of war photojournalism. He won a Pulitzer Prize for this image, and as he commented three decades later about the reach of his work, “Still photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world.”

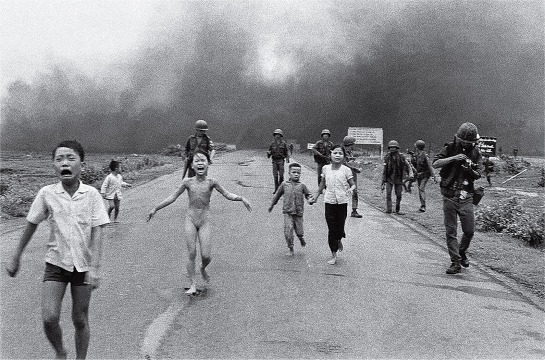

The faces of collateral damage and friendly fire are generally not seen. This was not the case with 9-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc. On June 8, 1972, Associated Press photographer Nick Ut was outside Trang Bang, about 25 miles northwest of Saigon, when the South Vietnamese air force mistakenly dropped a load of napalm on the village. As the Vietnamese photographer took pictures of the carnage, he saw a group of children and soldiers along with a screaming naked girl running up the highway toward him. Ut wondered, Why doesn’t she have clothes? He then realized that she had been hit by napalm. “I took a lot of water and poured it on her body. She was screaming, ‘Too hot! Too hot!’”

The Terror of War ~ Viet Nam 1972Ut took Kim Phuc to a hospital, where he learned that she might not survive the third-degree burns covering 30 percent of her body. So with the help of colleagues he got her transferred to an American facility for treatment that saved her life. Ut’s photo of the raw impact of conflict underscored that the war was doing more harm than good. It also sparked newsroom debates about running a photo with nudity, pushing many publications, including the New York Times, to override their policies. The photo quickly became a cultural shorthand for the atrocities of the Vietnam War and joined Malcolm Browne’s Burning Monk and Eddie Adams’ Saigon Execution as defining images of that brutal conflict. When President Richard Nixon wondered if the photo was fake, Ut commented, “The horror of the Vietnam War recorded by me did not have to be fixed.” In 1973 the Pulitzer committee agreed and awarded him its prize. That same year, America’s involvement in the war ended.

By April 2004, some 700 U.S. troops had been killed on the battlefield in Iraq, but images of the dead returning home in coffins were never seen. The U.S. government had banned news organizations from photographing such scenes in 1991, arguing that they violated families’ privacy and the dignity of the dead. To critics, the policy was simply a way of sanitizing an increasingly bloody conflict. As a government contractor working for a cargo company in Kuwait, Tami Silicio was moved by the increasingly human freight she was loading and felt compelled to share what she was seeing.

Coffin Ban ~ 2004On April 7, Silicio used her Nikon Coolpix to photograph more than 20 flag-draped coffins as they passed through Kuwait on their way to Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. She emailed the picture to a friend in the U.S., who forwarded it to a photo editor at the Seattle Times. With Silicio’s permission, the Times put the photo on its front page on April 18—and immediately set off a firestorm. Within days, Silicio was fired from her job and a debate raged over the ethics of publishing the images. While the government claimed that families of troops killed in action agreed with its policy, many felt that the pictures should not be censored. In late 2009, during President Barack Obama’s first year in office, the Pentagon lifted the ban.

.

.