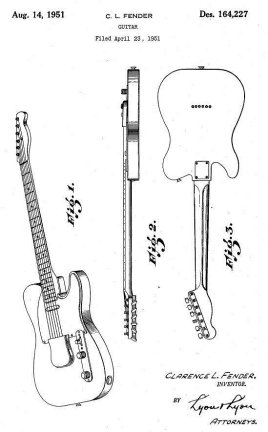

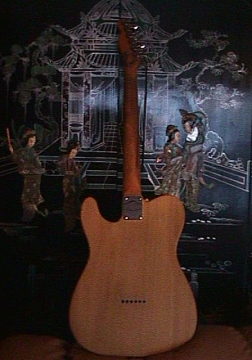

For '50s-era guitarists who would soon be playing rock

and roll, the Fender Telecaster hit the music industry with the impact

of the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs. Leo Fender's so-called "plank"

ushered in the era of the commercially successful solidbody -- echoing

the immense industrial and social impact of Henry Ford's Model T. While

Ford was never one of Fender's idols, the car maker bestowed the wonders

of the automobile upon the masses by standardizing a sound design, streamlining

production techniques, and lowering costs. Likewise, Fender's "Model T"

-- initially called the Esquire, then the Broadcaster, and finally the

Telecaster -- was a powerful, affordable tool that helped a vast community

of working guitarists ignite a cultural revolution.

The tumult was so far-reaching that

Gibson was compelled to introduce the Les Paul to compete with the Tele

-- and Leo himself was inspired to develop the Stratocaster in an attempt

o make its older sibling obsolete. These three models are still modern

music's most important guitars -- and they all have Leo Fender's 1949 "standard

guitar" prototype to thank for kick-starting their enduring glory.

THE ARCHTOP ERA

As twilight fell on the Big Band era

toward the end of World War II, small combos playing boogie-woogie, rhythm

and blues, western swing, and honky-tonk formed throughout the United States.

Many of these outfits embraced the electric guitar because it could give

a few players the power of an entire horn section. Pickup-equipped archtops

had reigned in these late-'40s dance bands, but the increasing popularity

of roadhouses and dance halls created a growing need for louder, cheaper,

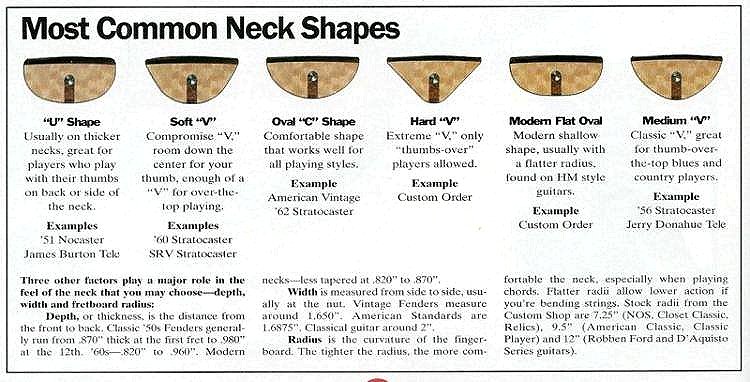

and more durable axes. Players also needed faster necks and better intonation

to play what the country boys called "take-off lead guitar," and Rickenbacker

Bakelites and other '30s-era solidbodies failed to deliver. Custom-made

solidbodies such as Merle Travis' Bigsby -- as well as kitchen-table

contraptions like Les Paul's "Log" -- pointed in the right direction, but

were beyond the means of the average player. The demand for better electric

guitars was as obvious as their reality was elusive.

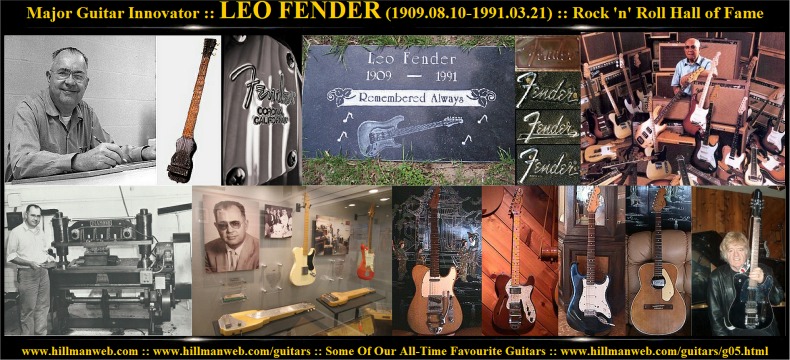

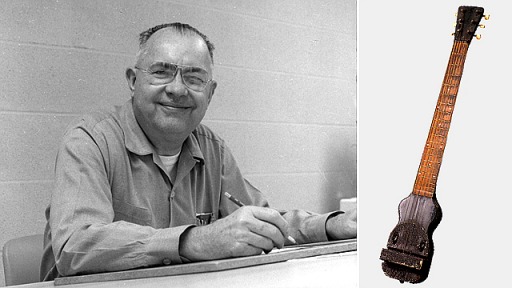

ENTER LEO FENDER

Fender recognized the vast potential

for an electric guitar that was easy to hold, easy to tune, and easy to

play. He also recognized that players needed guitars that would not feed

back at dance hall volumes like the typical archtop. (Many guitarists had

to stuff rags into their elegantly crafted guitars to stop the howling.)

In addition, Fender sought a tone that would command attention on the bandstand

and cut through the noise in a bar. By 1949, he had conceptualized the

perfect tone -- a clear, bell-like sound with distinct highs and lows,

but devoid of muddled midrange frequencies that Fender considered "fluff"

-- and began working in earnest on what would become the first Telecaster

at the Fender factory in Fullerton, California.

Although he never admitted it, Fender

seemed to base his practical design on the Rickenbacker Bakelite. One of

the Rickenbacker's strong points -- a detachable neck that made it easy

to make and service -- was not lost on Fender, who was a master at improving

already established designs. (He once said, "It isn't a radically different

thing that becomes a success; it is the thing that offers an improvement

on an already proven item.") Not surprisingly, his first prototype was

a single-pickup guitar with a detachable hard rock maple neck and a pine

body painted white (see Encore, page 160). The seeds of revolution were

sown.

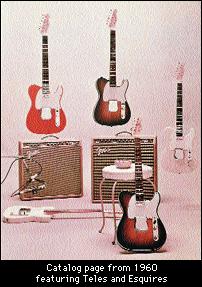

THE ESQUIRE

Don Randall, who managed Fender's distributor,

the Radio & Television Equipment Company, recognized the commercial

possibilities of the new design and made plans to introduce the instrument

as the Esquire Model. (Although Randall -- the company's de facto namesmith

-- gave the Esquire its moniker, Fender supported the name, saying that

it "sounded regal and implied a certain distinction above other guitars.")

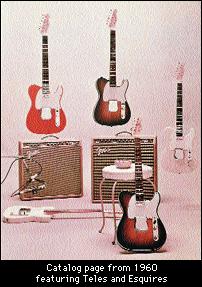

In April 1950, Radio-Tel started promoting

the Esquire -- the first Fender 6-string officially introduced to the public.

The company prepared its Catalog No. 2, picturing a black single-pickup

Esquire with a tweed form-fit case. Another picture showed Jimmy Wyble

of Spade Cooley's band holding a blonde Esquire. These debut models, with

a planned retail price of $139.95, exhibited the utilitarian shape of thousands

of Fender guitars to come.

"The Esquire guitar features

a new style of construction which vastly improves the useability of this

type of instrument," Randall wrote. The claim was further embellished by

stating that the guitar could be played "at extreme volume," and that the

fast neck was an aid to easy fretting.

Randall added, "The neck is also replaceable

and can be changed by the owner in approximately ten minutes time. This

feature eliminates costly repairs and refretting." Fender believed that

the neck was strong enough to resist warping without a trussrod. If a neck

did warp, he planned to mail the customer a new one in a shipping tube.

Unfortunately, the necks didn't turn

out to be as tough as Fender claimed. Randall reported that the necks on

his samples had warped badly while traveling to the 1950 summer trade shows,

and asked that the new guitars be outfitted with reinforced necks. Initially,

Fender had been contentious about the extra effort it would take to design

and manufacture reinforced necks, but then a test guitar in his lab suffered

the same problem. Faced with mounting evidence that his guitar truly needed

a reinforced neck, Fender bought a routing plate to install trussrods on

October 3, 1950.

Randall's primary marketing ploy was

to establish the Esquire in music instruction studios, reasoning that the

affordable, practical guitar would be a hot commodity in those circles.

In addition, a healthy response for the one-pickup version would prime

the market for the more expensive two-pickup model that Fender already

had in mind.

In fact, Fender's choice of a 3-position

lever switch -- which allowed three distinct guitar tones -- probably coincided

with his plans to add a rhythm pickup. Fortunately, the Esquire's body

design easily lent itself to both one- and two-pickup configurations. Ultimately,

all production models had cavities routed for two pickups because Fender

wanted players to have the option of adding a pickup in the future. (The

one-pickup models hid an empty cavity under the pickguard.)

The two-pickup Esquires were manufactured

with the second (rhythm) pickup positioned under the strings near the end

of the fingerboard. Fender shielded the rhythm pickup with a metal cover

to cut high harmonics and to emphasize fundamental tones. A handy blend

control knob mixed the rhythm pickup signal with that of the lead pickup

when the pickup selector was in its lead position. Putting the selector

in the middle position activated the rhythm pickup alone. In the forward

position, the rhythm pickup was also selected, but along with a capacitor

that rolled off high frequencies. (Fender called this sound "deep rhythm,"

and reasoned that guitarists could use the position to play bass lines.)

Dual-pickup Fender guitars featured these same electronics until 1952.

Although the single-pickup guitars

used capacitors to mimic the mellow sound of a rhythm pickup, the real

thing sounded better. Jimmy Bryant, who epitomized the new wave of postwar

electric-guitar wizards, liked the jazzier sound of the dual-pickup guitar,

as did Fender himself.

THE BROADCASTER

The factory finally went into full

production in late October or early November 1950. However, as Fender wanted

his best guitar in the hands of professionals as soon as possible, the

factory produced only dual-pickup Esquires. Fender's decision compromised

Radio-Tel's earlier marketing strategy, forcing Randall to hold orders

for the single-pickup Esquire and come up with a new name for the two-pickup

model. The name Randall chose was "Broadcaster." No one is sure of the

exact day he coined the name, but it coincided with the introduction of

the trussrod, as no authentic non-trussrod Broadcasters are known to exist.

(Dealers who insisted on Esquires had to wait until the single-pickup guitars

went into full production in January 1951 and were delivered the following

month.)

Musical Merchandise magazine carried

the first announcement for the Broadcaster in February 1951 with a full-page

insert that described it in detail. The guitar had what Randall called

a "Modern cut-away body" and a "Modern styled head." And what player could

resist the "Adjustable solo-lead pickup" that was "completely adjustable

for tone-balance by means of three elevating screws"?

Finally the industry had an up-to-date

production solidbody. (Fender sold 87 Broadcasters on the guitar's initial

release in January 1951.) Many people took note -- including Gretsch, who

claimed the Broadcaster name infringed on the company's trademark "Broadkaster."

Faced with this fact, Randall wrote a letter to his salespeople on February

21, advising them that Radio-Tel was abandoning the Broadcaster name and

requesting suggestions for a new one.

On February 24, Randall, who had some good

ideas of his own, announced that the Broadcaster was renamed the "Telecaster."

The Broadcaster-to-Telecaster name

change cost Radio-Tel hundreds of dollars, and derailed the initial marketing

effort. Brochures and envelope inserts were destroyed, and some unlucky

worker had to clip the word "Broadcaster" from hundreds of headstock decals

with a pair of scissors. For several months, the new twin-pickup guitars

sported nothing but the word "Fender." Years later, collectors would

coin the term "No-caster" for these early-to-mid-'51 uitars.

TELE TWEAKS

In 1952, Fender replaced the Telecaster's

blend control circuit with a conventional tone control. Now the switch's

rear position selected the lead pickup, the middle position selected the

rhythm pickup, and the front position delivered the "deep rhythm" sound.

Teles were equipped this way until the mid-'60s, when the modern switch

setup was introduced: the middle position selected both pickups, the front

position selected the rhythm pickup, and the rear position selected the

lead pickup.

One drawback of the 1952 to mid-'60s

wiring is obvious today: The wiring made a two-pickup combination impossible

unless the player delicately positioned the spring-loaded switch between

settings. However, once players learned this trick, they received a tonal

surprise: Different models produced different dual-pickup sounds, depending

on the rhythm pickup's magnetic polarity. The "between" setting -- which

helped define the mystique of vintage Telecasters -- could offer the robust

tone provided by both pickups or produce a snarly growl similar to the

Stratocaster's half-switch sound. (James Burton, playing his '53 Telecaster,

exploited this unique tone on Ricky Nelson's "Travelin' Man.")

However, it was the Tele's lead pickup

that captured the hearts of most players. Early "level-pole" units offered

outstanding tone with significant bass content and non-offensive highs

(although manufacturing inconsistencies caused a small number of these

pickups to produce an out-of-balance, bass-heavy low-E sound). In mid-1955,

Fender staggered the polepiece heights as he had on Strat pickups. The

results were mixed. The volume balance from string to string was better,

but the Tele's overall sound was harsh.

The earliest guitars featured steel

bridges that were ground flat on the bottom. By the end of 1950, Broadcasters

boasted brass bridges with the same tooling marks as the earlier steel

ones. In 1953, the factory began notching the two outer brass bridge pieces

under the low E and high E, which allowed a lower adjustment for these

strings. By 1954, Telecasters employed steel bridges again, but they were

rounded and made from a smaller-diameter stock than the 1950 bridges. By

1958, the bridge pieces were changed yet again to a threaded stock with

less mass, and the factory stopped putting the strings through the body.

As a result, late-'50s models represent the shrillest-sounding and perhaps

the least desirable Telecasters made during the pre-CBS (pre-'65) era.

In 1959, Fender introduced the Telecaster

Custom and Esquire Custom, fancy versions of the originals with white binding

that helped protect the edges from wear. These guitars had Jazzmaster-like

rosewood fingerboards, which looked more traditional and wore better thanone-piece

maple necks. Some early-'60s, pre-CBS Custom Telecasters had necks capped

with maple fingerboards made in the same manner as the necks capped with

rosewood. However, at no time during the pre-CBS years did Fender regularly

produce Customs with the older-style maple neck. (The only exceptions may

have been unlikely special orders.) While the standard Telecasters and

Esquires came with blonde finishes, the Customs were offered with sunburst

finishes. A few even had more expensive custom colors. Moreover, Fender

made some Teles with mahogany bodies in the '60s.

THE PLAYER'S PERSPECTIVE

In the early 1950s, a broad spectrum

of Tele players established themselves in combos -- even young blues legend-to-be

B.B. King spanked the plank. With its versatile sound, ease of playing,

and reasonable cost, what better guitar to yellow with perspiration and

cigarette smoke? Most serious students could afford the $189.50 price,

ensuring a new guitar generation would grow up on Fenders. Still, most

players preferred top-of-the-line instruments, and almost all professional

jazz and pop players employed something other than a Fender. And after

Fender introduced the Stratocaster in '54, the Tele wasn't even Fender's

top-of-the-line ax.

Then an interesting thing happened.

By the late '50s, the Telecaster was becoming an integral part of the session

player's arsenal. California-based guitarist Howard Roberts endorsed Gibson

and Epiphone but also played an old Telecaster on countless rock sessions,

as did Tommy Tedesco. These players knew what models recorded best and

pleased record producers. The Telecaster and its solidbody cohorts produced

the teenage sound that proclaimed a guitar generation gap: old versus new,

jazz and pop conformity versus rock rebellion. At the same time, the Tele

was heard increasingly on pure country recordings, treading in the big-box

domain of Chet Atkins and Hank Garland (who sounded anything but twangy).

As the '60s unfolded and rock guitar playing

matured, the Telecaster's role, onstage and off, solidified. While the

guitar played a small part in the rise and fall of instrumental rock and

surf music, Steve Cropper played one with Booker T. and the MGs, as did

the Ventures' Nokie Edwards. James Burton and Tele moved from Ricky Nelson's

band to TV's Shindogs, all the while chalking up hours as L.A.'s premier

session stylist in rock and country.

As the '60s unfolded and rock guitar playing

matured, the Telecaster's role, onstage and off, solidified. While the

guitar played a small part in the rise and fall of instrumental rock and

surf music, Steve Cropper played one with Booker T. and the MGs, as did

the Ventures' Nokie Edwards. James Burton and Tele moved from Ricky Nelson's

band to TV's Shindogs, all the while chalking up hours as L.A.'s premier

session stylist in rock and country.

Much of the British Invasion had the

look of Rickenbackers and Gretsches, but Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck recorded

many of their milestone sides with the Yardbirds on a Telecaster and Esquire,

respectively. Mike Bloomfield chose a Tele for his highly influential mid-'60s

work with Paul Butterfield and Bob Dylan, and Jimmy Page played one on

Led Zeppelin's first album and on the solo of "Stairway to Heaven."

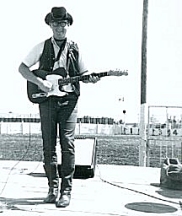

As Roy Buchanan told Guitar Player

in '76, "The Telecaster sounded a lot like a steel, and I liked that

tone. I like the old Teles because of the wood, the way the pickups are

wound, the capacitors, and the whole works."

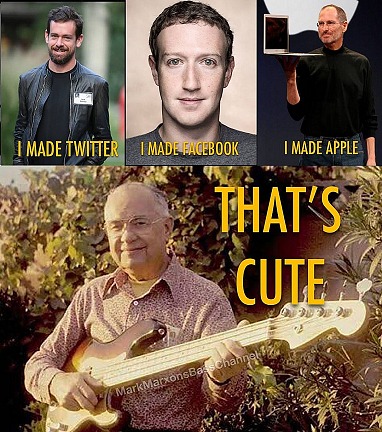

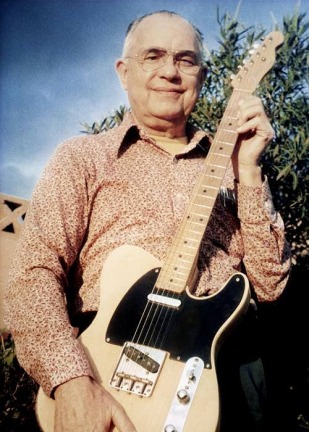

THE TELE LEGACY

By the late '60s, it was clear the

Telecaster had shaken the foundations of the music industry. The Tele --

and the host of solidbody models introduced as a result of its success

-- changed the way the world heard, played, and composed music. Ironically,

Leo Fender, who worked incessantly after '51 developing new models such

as the Strat, Jazzmaster, and Jaguar (and then, in the '70s and '80s, formulating

Music Man and G&L models), had a very hard time topping what he accomplished

in his first go-round.

"Everyone thought his first guitar

was his best, but no one would tell him that," said longtime friend and

pioneering electric stylist Alvino Rey in the '80s. The Tele was Leo Fender's

Model T, but, unlike the old Fords, it didn't go away. For thousands of

guitarists, the Telecaster is still state of the art -- an enduring battle

ax for rock, country, or anything amplified.

THE WHOLE STORY

For a more comprehensive tome

on the history of Fender guitars, check out Richard R. Smith's Fender:

The Sound Heard 'Round the World [Garfish Publishing]. In addition to curating

the 1993-94 exhibition "Five Decades of Fender" at the Fullerton Museum

Center and writing articles for numerous guitar publications, Smith worked

with Leo Fender himself, testing the master's late-career prototypes.

.

. .

.

.

.