|

WEB GRAFFITI ZINE Zine 20v2: First Nations Collated by William Hillman Assistant Professor ~ Faculty of Education ~ Brandon University

|

|

WEB GRAFFITI ZINE Zine 20v2: First Nations Collated by William Hillman Assistant Professor ~ Faculty of Education ~ Brandon University

|

|

Native American Words of Wisdom David Westfall Photo Westfall/Castel Memoir 3: Muskrats, Cold Weather, Canoe Journeys and a Church Bell Art Gallery Robert Castel Photo Westfall/Castel Memoir 5: The Mimikwisiwak and the Little People of Granville Lake and Burntwood Lake Cartoon Reference Links |

"The Pueblo have no word that translates as "religion".

The knowledge of a spiritual life is part of the person 24 hours

a day, every day of the year.

Religious belief permeates every aspect of life;

it determines man's relation with the natural world and with his

fellow man.

The secret of the Pueblo's success was simple.

They came face to face with nature but did not exploit it."

Westfall/Castel

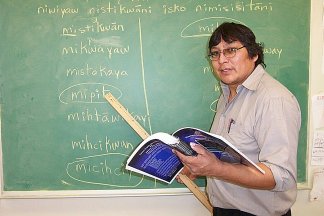

English-Cree Dictionary and Memoirs of the Elders

David Westfall

Memoir 3

Muskrats, Cold Weather, Canoe

Journeys and a Church Bell

Pukatawagan, January 12, 1998

Interviewer: Doris Castel

![]()

I was born on a bay, at a place called The Swirling Narrows (Opachuanau), near People’s Lake (South Indian Lake), on October 24, 1916. I don’t remember my early childhood, but when I was about ten years old I accompanied my grandmother to trap muskrats in the spring, just like long ago. Boy, there were lots of muskrats in that place. It was along the Missinippi River that flows here, you know, and we did not have to go far before we found muskrat burrows, where my grandmother had set a trap. We set up camp nearby, and whenever we detected a little stick moving, we knew we had caught a muskrat. It was the anchor stick that told us when a muskrat had been caught. Immediately, my grandmother would go and get the muskrat and hit it. Then we roasted and ate the muskrat, all the while watching to see if another one had been caught in a trap.That’s how we were brought up. We set nets, too. There were a lot of sturgeons, too, in the Missinippi. Anyone who set a net would catch a sturgeon right away. Nowadays, there are no sturgeon left, but back then, boy, they were plentiful. It was like today, when anyone sets a net, he catches fish. At that time, if anybody set a sturgeon net, he had caught four or five sturgeons by the next morning. That’s how abundant the sturgeons were long ago. And that’s how life was for the people then.

I finally went to school when I was about ten years old, when the residential school at Sturgeon Landing opened up in 1926. I attended that school at Sturgeon Landing, eighty miles to the west. Back then, the Sturgeon River was really wild and isolated. It felt like uncharted territory when we first went to school there, but now a road leads there and anybody can drive in. It is so different now.

After I finished school, I went trapping with my father. We trapped here at Old Man’s Bay, his favourite trapping spot. We went out into the bush, camping wherever we stopped, but we did not use a tent at all. We slept out in the open, and, boy was it cold! It was not like today, when if it is twenty-five below we think it’s cold. It was fifty or sixty below back then, and we slept on the open ground! Many people lived like that long ago. There are not many of us left today who experienced that, for example, Adam Castel, Emile Sinclair. There are only about three of us now who experienced that cold. And now, the younger generation does not want to believe how cold it was. They say that we are lying. But no, Pete Mitchell experienced it, too. He tells about the time he camped outdoors while working for the Department of Natural Resources. He used to sleep outdoors then. He said it was like somebody hitting the trees, which just split. It was so cold that the trees would split open, he said. That’s the way it was.

Eventually, I started to trap on my own, but I used a tent and a small wood stove. Fortunately, I made a good living, although the times were hard. I used to stay outdoors all day, no matter how cold it was. I went to bed only when it got dark. I was comfortable there until close to dawn, when I felt the cold. When you lived like that, you just had to get up and eat, only first you had to thaw your food. Your food was always frozen until it was cooked. Only where you had set up camp did you eat something nice and warm. Imagine this! You travel out in the bush all day, and meanwhile all your food freezes up. When you want to eat, you thaw just enough to eat. It was a difficult life back then, when our generation was growing up.

Now, old age has caught up with me and I receive social assistance, an old age pension. Now I think I am a “king,” especially when I think back to the hard times of long ago, when I was about thirty-five. I reflect on my past life and compare it with life today, and, boy, I think I am a king. How time changes lots of things, compared to the past. That’s all I have to say.

Oh, one more thing! I’ll tell about my late grandfather Mathias Colomb. He came from somewhere over there to the south. He was not born around here in the north, but lived somewhere down south. In his time, those white people were pushing inland towards the north. They were always fighting each other, and the whites and Natives were not levelling with each other. That’s when my grandfather thought of coming up north. He used to travel by canoe. Maybe he paddled along from Winnipeg and then, eventually, to The Pas and Cumberland House, and then to Sturgeon River and Pelican Narrows. Then, maybe, he stayed for a while at Pelican Narrows, but he did not like it there. He thought of looking for a place where he would be able to make a good living. So, he paddled out from Pelican Narrows and travelled along what is now called SandyBay. He crossed Loon Lake and eventually came to Duck Lake, where he stayed for quite a while, to sightsee and check out the land. When he was satisfied, he thought, “I will continue my journey down the river.”

Soon, he paddled into Pukatawagan, over here. He stayed here, looked around, and boy, was he pleased with these rivers, the four rivers that flow into one. And here, boy, they caught lots of fish. People used to fish here at the narrows. There was this church at the narrows. Today, a road connects to the other side, and that’s where they set their nets. Back then, boy, they caught a lot of fish. And that’s how Pukatawagan got its name, “fishing spot,” named after the narrows where they set their nets. The four rivers that are located here all have names, like the Pukatawagan River here, Leech River, and the Hanging-Upside-Down Place, and Between-the-Two-Rivers. Towards the Hanging-Upside-Down Place and, halfway to the Hanging-Upside-Down Place is between-the-Two-Rivers, Chaschawaweyask. Then, after that time, my grandfather made camp at Pukatawagan.

It was one hundred and thirty-one years ago, and that was when the settlement of Pukatawagan was established. And it was then that the Hudson’s Bay Company set up a trading post. They brought in food here. The people had to paddle from here with a canoe to The Pas to get provisions, the things they needed. They would go to The Pas to get flour, lard, sugar and tea. They paddled, maybe, four hundred miles. In June, the “egg-hatching month,” they would go out, and they would be back in July, the “flying-up month.” They travelled out again until September, the “rutting month.” Then they came back home. They travelled by canoe only twice a summer, and that was all they could manage. Those people of long ago were fit and agile. They had no difficulty paddling to The Pas twice a summer. If we were to paddle all the way to The Pas today, we would probably never make it back, we would probably… maybe we would freeze! The people today are so different from the way they were then. Back then, they ate only moose meat, fish, duck, berries; everything they ate came from the land. They ate these things, and that’s why they were so strong.

I have one more thing to tell, but I don’t remember much. Oh, when we went to school at Sturgeon Landing, we travelled there from Pukatawagan for the first time in 1926. There were about ten of us when we first went out there to school, when it first opened up. All the children had to paddle. We paddled in, but we did not have an outboard motor then. There was no such thing. We just paddled, and at a portage everyone had to carry something over, the provisions and gear. And that’s how we travelled. Eventually, by the time I finished school, a train was running here at Sherridon, where a mine had opened up. That’s where the train stopped. One time, in 1931, after I had got out of school (for the year), I finally went on the train. It was the first time I had taken a train. Before the train started running, I had to paddle home every July, July first, when the school year ended. They gave us holidays, right? They would release us then, and if anyone had children attending school at Sturgeon Landing, the parents had to go and pick them up to take them home for the holidays. But the last time was quite different. (The school had not yet burned down.) The children just had to go by plane. In the fall, they were flown to school. They just had to go by airplane, and boy, we had a hard time at school the first time. Those children who flew were, boy, like kings. They only had to sit and look out the window. Now, I’m going too far, lying too much.

When the first church was built here... Actually, there were four churches. I saw two of them, but the first two were before my time. One time, back in The Pas, you know, there was a church bell that was used to call people to service. Then, the priest wanted somebody to transport the bell to Pukatawagan. Four men went with two canoes to get it. They paddled two in a canoe, Julien Bighetty, an elder, Alex Dumas, another elder, my father, and my uncle Solomon Colomb. These were the men who went out and got the bell from The Pas. The paddled along by Cumberland House, and then Sturgeon River. Continuing their journey, they finally reached Kississing Lake, as we call it. They passed also by Cold River, as it was called. Boy, they travelled a long time, because there were many portages to carry the bell over. It was very heavy, they said. At the portages, they tied two sticks onto it and carried it at each end, by themselves, the four men. The last portage was Jack Pine Portage, a very long portage. They carried the bell over, stopping halfway. There, the elder Julien said, “Yes, we managed it, to bring in the bell. Boy, was it heavy! We should be happy,” he said. “And we made it,” said Alexander Dumas, “and.... but wait, man, I will ring the bell.” Boy, they stopped there a while at the portage just to ring the bell! That is how happy they were to bring in the bell for Pukatawagan. And that is how my father used to tell it. He would talk about it and laugh. Alexander Dumas is the one who rang the bell.

Okay, now I’m sure that is all I want to tell, what I had in mind to tell about.

[End of recording]

Westfall/Castel

English-Cree Dictionary and Memoirs of the Elders

Robert Castel

Memoir 5

The Mimikwisiwak and the Little

People

of Granville Lake and Burntwood

Lake

Keno Linklater, 1936-

Pukatawagan, May 27, 1998

Interviewer: Beverly Linklater

![]()

Beverly: Do you recall if your grandfathers ever told you stories about

merpeople, the omîmîkwîsiwak, whether they existed or if they had ever

seen them?Keno: Yes. I remember that. Yes, it was one of my grandfathers, my

mother’s father to be precise. There is a so-called Mîmîkwîsi Rock in

a place where people are living now [Granville Lake reserve]. It is

just across the lake, just a short distance away.My grandfather used to tell me the story of an old man who always

set his net there at the Mîmîkwîsi Rock. A lot of fish were caught in

that spot. This is his story.One day, an old man set his net there. He checked his net every

morning for three or four days, but there were never any fish in it.

Finally, he lay in wait to see who was stealing his fish. He made his

look-out in the bay behind a point of land near the Mîmîkwîsi Rock. He

hid and waited there in a birch-bark canoe.Eventually, he heard talking. He could understand them because

they were speaking our language, Cree. (“They talked Cree, like us,”

said my grandfather.) And this is how he told the story: He sneaked up

on them while they were in their canoe, but I don’t know what kind of

canoe they were using.“So you are the ones who have been robbing me of my fish, eh?”

The one who was steering the canoe turned around. Meanwhile, the other,

the younger one, was lifting the net. Both of them were hanging their

heads down. Now, the one who was steering said to his companion, “You

are better looking. You lift up your head and talk to the old man.”

(Those mîmîkwîsiwak don’t have noses, you know, and their chins are

like a fish’s jaw. They have teeth, too, and their eyes look human. But

from here on, he could not see clearly how they looked. Their clothes

look like a fish’s skin, and their bodies really shine. They seem to

glow or glisten.)Well, the younger one lifted up his head, looked at the old man

and said, “It’s because we are hungry. Even though we have set our nets

in the big lake, every time we check them there are no fish. And we see

this old man, you, catching so many fish. We tried, over there, to show

you this huge rock, such a beautiful one.”That rock is still there to this day, you know. I see it all the

time. It was not always there, but suddenly dropped down from

somewhere. It is hollowed out in spots, scooped out as with a big

spoon. They made it, but I don’t know what kind of tools they used.

There, beneath the water is where they lived. No, not in the water

itself, but in a house like this one, the old man said. He told my

grandfather that he was taken down under the water to see the home of

the mîmîkwîsak. It was incredibly beautiful down there, where I assume

they did their cooking because I saw firewood. I don’t know just how

they made their living, though.And then there was another guy, Peter [Colomb], who told me a

story, too. This one is from Burntwood Lake. There, too, is a place

where the mîmîkwîsiwak used to live, and maybe they are still there

today. Quite unexpectedly, he told me to go and see for myself. (He

told me the story at the time I was working for the government.) “Just

go and take pictures of it,” he told me. “You will see how obvious it

is that they were there, those mîmîkwîsiwak.” And he told the same

story, how the mîmîkwîsiwak have no noses, like fish. And their mouths

and chins look like fish, too. They had teeth, I assume, because they

ate all kinds of things. That’s what the old man said. He told me this

story quite recently, in the 1960s.Now, back to Granville Lake! My grandfather said that still

today, they are there, at Granville Lake’s Spirit Island. That’s where

the mîmîkwîsiwak took refuge. People will say, “I don’t believe in that

myself.” But if you point to it, even if the water is calm and crystal

clear, not five minutes away there will suddenly be whitecaps and a

strong wind. I believe it, too.One time when I was out fishing there in the 1950s—I was already

married in the summer of ‘58—I was with my friend Sandy Patterson. We

were not taking anything seriously. The water was perfectly calm when

we came out across Granville Lake to that wide-open area in the middle

of the lake. My friend stood up and pointed a finger at the very Spirit

Island, saying, “Let’s see if it is true, what they say.” “Don’t do it,

my friend, or we will perish.” We got close to the shore just in time,

but we capsized there. Our fish were floating all over the place. Our

nets, too, and we lost them all. They just drifted away, and we had to

swim to shore. Our boat sank there, about twenty feet from shore.

That’s when I came to believe, too.It’s the same here at Highrock’s Little Spirit Island. When

somebody points a finger at it, the wind comes up right away. I believe

that. I believe it, so nobody should be caught unawares or be misled

into thinking there’s nothing to the story. When you hear it, it is a

lesson for the future.If you are travelling to this Granville Lake Spirit Island, you

are not to point a finger at it. You are not to play around with it, or

you could drown. The same is true of the island at Highrock. It is

true. Even if you have a fast outboard motor, the wind would still have

time to catch you. That’s the mîmîkwîsiw. The omîmîkwîsiwak still exist

today.It’s true, and also, you know, long ago these little people, or

dwarfs, as they were called, existed, too. Well, people really used to

see them long ago, just as my grandfather used to tell me about them,

my father’s father, you know. He said, “I believe in them, my grandson,

those little people. We did not see them, but they lived among us.” And

there are also some of them over there at Granville Lake. In fact, my

younger sister, Harriet Baker, has seen them them out there in the

lake, as well as other people who lived there, such as my brother-inlaw

August Merasty, and my younger sister Marie Merasty.They were there once, going across there in the middle of the

night, to visit somebody. They were in their younger years at the time.

It was the first time over there, when my brother-in-law, Louis Baker,

had just married her.They probably went over there for a party, and he was perhaps

getting a bit high. He came home alone in the night. As he was walking

in the place where there used to be a fish packing house, he said, “All

of a sudden somebody grabbed me on my back. Boy, did I scream! I was

not drunk, though. I grabbed, in vain, a person that I felt behind me.

I don’t know what he did to me. Then, another one grabbed me by the

legs. I grabbed the one on my back and threw him. Finally, one of them

let go and then both of them fled. I watched them run away.”They were not big, those little people. Even today, the little

people live among us, but I don’t think anybody ever sees them. My

grandfather said, “The little people still live among us today, but we

don’t know it.” They still exist. It is true, and so we should take it

as a warning for the future. A person should watch out and not make

light of it, in order to have a good life. All kinds of things can

happen if we do not take it seriously.People used to be blessed with different gifts. We all have

different gifts or talents. The same is true of the animals, if a

person fools around with them. Long ago, my grandfathers told me about

this.A person who kills an animal should be really careful about

spilling the blood. If a woman steps over it, she will scrub it right

away. That’s what they said, not the way things are today. But maybe it

still happens. I follow this same custom myself. Even if I am given

some meat, I am very careful with it. I watch to see that the blood

does not drop onto the floor. If it does, I mop it up right away. And

in the future, you will see it in this light, you know, you who will be

in your younger years three generations from now. By the time you hear

me, I will be gone.These are the stories that I heard long ago. They were my

grandfathers’ stories, and they were really old when they left this

world. I was very young when they told me the stories.Thank you. That’s all!

Up To Webzine 21 Title

![]()

REFERENCE LINKS

![]()

David Westall's

Northern Manitoba Mosaic

Index

of Native American Museum Resources on the Internet

Native

American Homepages

Hayehwatha

Native American

Resources at the Smithsonian

American Indian

Music: Audio Samples

The

Horse in Blackfoot Indian Culture: Online Book

Native American

Portrait Gallery

National Museum of the

American Indian

Sioux History

PUKATAWAGAN: Reflections

of a Wimistikosiw Visitor

![]()

![]()

![]()

WEBZINE

ARCHIVE

Hillman

Eclectic Studio

All Original Work ©2009/2014 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners