|

WEB GRAFFITI ZINE Zine 20v5: First Nations Collated by William Hillman Assistant Professor ~ Faculty of Education ~ Brandon University

|

|

WEB GRAFFITI ZINE Zine 20v5: First Nations Collated by William Hillman Assistant Professor ~ Faculty of Education ~ Brandon University

|

NATIVE AMERICAN WORDS OF WISDOM

"Treat the earth well: it was not given to you by your parents, it was loaned to you by your children. We do not inherit the Earth from our Ancestors, we borrow it from our Children. We are more than the sum of our knowledge, we are the products of our imagination. "

Ancient Proverb"!Ama Sua, Ama Kjella, Ama Lllulla! - Don't lie, don't cheat, don't be lazy".

Quechua greeting during Inca times"The death of fear is in doing what you fear to do."

Sequichie ComingdeerThe word Inca means "Children of the Sun". "Sukay" is a Quechua word meaning 'to open the earth and prepare it for planting'."

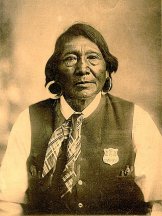

Learn to associate with the White man, learn his ways, get an education. With an education you are his equal; without it, you are his victim.

Chief Plenty Coups, CrowWhy not teach school children more of the wholesome proverbs and legends of our people? That we killed game only for food, not for fun... Tell your children of the friendly acts of the Indians to the white people who first settled here. Tell them of our leaders and heroes and their deeds... Put in your history books the Indian's part in the World War. Tell how the Indian fought for a country of which he was not a citizen, for a flag to which he had no claim, and for a people who treated him unjustly.

Grand Council Fire of American Indians to the Mayor of Chicago, 1927

|

"I don't make jokes, I just watch the Government and report the facts..." "There is nothing as stupid as an educated man if you get him off the thing he was educated in." "Everybody is ignorant, only on different subjects." "A man that don't love a horse. . . there is somethin' wrong with him." "There is no income tax in Russia. But there's no income." "People are marvelous in their generosity if they just know the cause is there." "We will never have true civilization until we have learned to recognize the rights of others."  |

Castel’s English-Cree Dictionary and Memoirs of the Elders

Memoir 9

Memories of My Childhood

Athanase Castel, 1930-

Pukatawagan, November 11, 1998

Interviewer: Robert CastelAs soon as I was old enough, I accompanied my father when he went

trapping. We had a team of good, strong dogs. I watched how he set the traps

but did not set them myself. My job was to look after the dog team and load

the furs that he caught, the lynx, you know. I would tie them onto the sled

as I came to them. He would move on after checking each snare, beginning

first thing in the morning. Whatever he had killed, he would just put beside

the trail. I came along after him and loaded up the furs. The lynx gave me a

hard time, you know, because some of them were frozen in an awkward position.Also, the portage was densely overgrown. Sometimes I would have to load six

or seven onto the sleigh. I had to straighten them because of they were

frozen in awkward positions. It was difficult, because the fur could tear,

especially in the arm, which could break. Then one loses that fur, although

it can still be attached by sewing it together, as my mother used to do.

January used to be a very cold month, much colder than it is now. My

father did not check his traps in January because the animals did not move

around then and nothing would be caught anyway. “It is too cold,” he told me,

“for the animals to be active.” For example, the mink went under the rivers

and not one of them even left tracks in January. In fact, all of the furbearing

animals went underground in January. The lynx gathered in one place,

you know. The rabbits stayed put and did not go far. A month later, the

animals all started to disperse. Then we would go to check our traps. We came

home for the cold month. Sometimes it was so cold that we could hear the

trees when we slept. It sounded as if somebody was chopping them. Since then,

I have never seen the temperature drop so low.It was so cold then that if a dog did not eat for one night he would

starve and freeze to death. A dog had to be well-fed to survive. When we used

dogs, we built them little houses where they stayed. There was a piece of

cloth for a door, and every time they went in, they automatically closed it.

I nailed a piece of cloth around the door like this. A dog could come and go

at will. There was no problem. He would warm himself up in his house when he

slept. I put straw in the dog houses. That is how we treated our dogs. So did

my older brother. He’s the one I went trapping with when I stopped going with

my father. We did the same things I used to do with my father. It was

difficult, really difficult.The caribou used to come by here, too, and they were plentiful. I don’t

remember exactly when that was, but it was quite a long time ago. There were

a lot of caribou over at Fine Gas, where the winter road passes by, as well

as at Halfway Island and at Duck Lake. They were everywhere, and they were

plentiful. They used to stay here all winter. They would arrive at freeze-up,

and that’s when I used to go with my father. Times were very hard then, but

we were never selfish. Everything was shared. My father always killed a moose

because he was skillful, agile and strong. I only butchered the moose myself,

you know, and took home whatever he killed.At that time everything was sold cheaply, not like today. Then, you

could buy a lot of groceries for twenty dollars. The canned goods cost less

than a dollar. The ones that cost five dollars now cost only eighty or ninety

cents then. Cans of pork and beans cost only thirty cents, the small ones.

And nowadays everything is so expensive. A hundred pounds of flour used to

cost just four dollars, and two dollars for twenty-five pounds. Things were

quite cheap then. My father used to get his groceries from Cold Lake. He went

by dog team from here. We used to overwinter at Duck Lake and came in only

for Christmas Midnight Mass.Not many of us lived here then, and it is only in recent years that

people have been moving in here from, for example, Granville Lake. This oldtime

chief was one of them. None of them are still living. They came from

Granville Lake and from Highrock, too. Eventually, our population began to

increase, until finally there are a lot of us today, right? Although there

were not many of us here, we already had a resident priest, the one in the

picture. He was young when he first came here. He was a religious brother,

you know, the one who lived here among us. Eventually, he started to build a

church, the one that was torn down [in 1995]. It is the one that was built at

that time, quite a long time ago.This brother raised dogs, too. He used them to travel around before

Christmas. He visited the people who gathered at Midnight Mass. They lived

all over the place, for example, at Granville Lake, Loon Lake and Russell

Lake. He went by dog team to Russell Lake, and to Sandy Bay, as well as to

that place close to here called Scattered Birch River. He travelled

everywhere, even to Highrock.This was our priest. He was a strong person. He was very strong while

he was still in good health, you know, and he was very fast. At one time, he

kept good dogs, and he had so many of them. One time he had good dogs that he

had raised himself. He took five puppies from one bitch and raised them. He

had really good dogs. At one time, he used to travel from here to get fish

from the fish warehouse at Duck Lake, on the shore at the confluence at Duck

Lake. It was by the creek. At eight o’clock, after a mass service there, and

after he had eaten, he went and got some fish. He would load them up and be

back by twelve o’clock. He would make it back to this small portage at the

little lake by twelve, according to Jonas, who used to go with him. They

loaded up two hundred fish apiece. It was quite far, on the other side of

Duck Lake, over at the fish warehouse by the creek. He had good dogs then,

but he used only four, and at the same time he would ride in the sleigh with

two hundred fish on board. Those fish had to be skewered. He pierced them

with small stakes to feed the dogs during the winter, you know. He fished in

the fall and stashed his fish over there; that’s where he would go for more

when he was running short. That is what this priest did: he would travel

around. Eventually, his health failed, but he was all right for quite a long

time before he started getting sick. When the sickness caught up with him,

began to decline slowly, and he gradually went down. That is what happened

![]()

![]()

Castel’s

English-Cree Dictionary and Memoirs of the Elders

Memoir 10

How the White Man Took Care

of a Wihtiko

Athanase Castel, 1930-

Pukatawagan, November 11, 1998

Interviewer: Robert Castel

![]()

Well, the wihtiko would not eat a white person, you know, just Indians.Those white people used to be all over, too, long ago. One time a wihtiko came upon a white man who had whiskey. It did nothing to the white man, whereas it would have attacked an Indian right away. This white man made a home for the wihtiko, made him comfortable, you know. He started caring for it by giving it food. But the wihtiko would not eat properly. It refused what was offered. Well, the white man poured the wihtiko a glass of whiskey, and another and another. Eventually the wihtiko began to thaw, to melt. That’s because the wihtiko is frozen inside, iced up, you know. But the alcohol has the effect of making you sweat even if you are cold. You sweat right away.

And that’s what the white man did to it. He plied it with whiskey until it started to thaw. It started to leave him. It did nothing to the white man, whereas it would have harmed or killed an Indian right away. Now, long ago there were a few of the old people who knew how to overpower a wihtiko. But I don’t think the wihtiko ever killed many people, just a few of the old people long ago. It did not have a nice, kind way of life. I only heard about these wihtikos I am telling you about.

Castel’s English-Cree Dictionary and Memoirs of the Elders

Memoir 11

The Old Man Who Killed Two Wihtikos

and

The Flin Flon Wihtiko’s Footprints

Athanase Castel, 1930-

Pukatawagan, November 11, 1998

Interviewer: Robert CastelOnce there was an old man here who killed two of them. He got one when

it came from the north in the spring. (Wihtikos always came in the spring.)

It was not able to kill just anybody, though, because there were some people

here who were wise to them. They knew to run away to a safe place when the

wihtiko came near. Well, that old man killed two of them.One time he killed one out at a wilderness lake, and another time over

here at Cold River. People used to paddle there when they went to sell their

furs in the spring. As they were travelling along, the old man sensed one.

“I can feel it! Boy!” he told his companion. “We have to stop for a

while.” He knew it was there and he wanted to kill it. They headed back home

just as the sun was starting to set. They came by way of the river. At the

end of the lake was another river. That old man knew it was there, and he

wanted to destroy it.Okay, then, I think, “Right here,” he said, “this island.” It was

there. That’s where he said to drop him off. He disembarked. “Right here.

Drop me off right here,” he said. So, he was put ashore on that island. “In

the morning, as the sun rises, there will be a gunshot at the end of the

lake. Then, you paddle over there.” He told him to wait there, so he did as

he was told. “And when there is a gunshot, come paddling out. By that river

put in a stake. Tie up and anchor there. Don’t go ashore.” He was travelling

with his young son, who was not very big. They went over there, and he sat

with him in the canoe, just anchored there. At dawn the gun fired. The old

man who had dropped him off there fired the gun.He could be seen right there by the river, on a smooth, suitable rock.

He was just standing there and walking around. He started out to get him. He

went straight to the shoreline. And that’s where the old man went and killed

that wihtiko. “We got off at the edge of these high cliffs, where he pulled

the canoe ashore,” he said. He took his son out of the canoe. Then, he said

to him, “Make a fire for tea.” “Don’t you want to go and see it?” he asked

him. The boy said, “I don’t have the courage. I don’t want to see it.” “It is

right there, behind this rock,” he said, “just around the bend by this high

cliff. It is lying there.” His son replied, “Okay, but I don’t want to go and

see it.”They built a fire and made tea on a nice, level rock with a hollowedout

spot. He made a big fire and put two small rocks in it. No, they were big

rocks. Eventually the rocks turned glowing red-hot. “Pull my jacket over my

head,” he said. “Take it off and take that rock and rub it against me.” Now,

that rock was red-hot. “I don’t want to take it out of the fire,” the boy

said. “Just take it,” he told him. So he took it out, even though it was

glowing hot. “Rub my back with it,” the old man said. When the boy rubbed his

back with the rock, it cooled off right away. “Put it down and take another

rock from the fire,” he told him. After that, the old man said, “I am better

now.” He recovered. I assume he was cold in his back. Rubbing his back with

red-hot rocks cured him.It is not bad... strong, that wihtiko, because it is not a nice being.

It is not kind. People said it was some sort of a devil. But it was not like

that, those ones from the north. They were not being cared for. They came

from way over there, these Eskimos, from farther away than Brochet. They were

not being looked after long ago. Since then, none has come here. Not once did

one come here again, of those who started to freeze and go crazy and come

over here.One came over to Flin Flon. A white man killed one there. It walked by

here, that one. I tracked him myself, that wihtiko, but I never did get

close, you know. I only tracked him as I was going to lift my net over here.

Well, one spring I went and took my nets out. The ground was already becoming

bare, but I was using dogs when I went over to the other side of the bush.

Still, I had no trouble riding. Then, over there, out in the open, there were

snowdrifts. There were three footprints there. I stopped and had a look. Boy!

A wihtiko! They were already making tracks. It usually made tracks, people

said. “A bear should not be walking in there,” I thought. It was a wihtiko

that made three footprints there. I stopped and wondered what I should do.

“It is best to go home,” I thought. “But no, I might as well check it out.”

I told my dogs to move. We had not gone very far when the sky cleared. And a

little further on, the sun was suddenly covered by a cloud. It was not a big

cloud, but suddenly there was a big snow storm. Boy! Nothing could be seen.

There was no visibility, so I stopped. Snow was just pouring down. After a

while, the sun came out again and the sky cleared. The snow could be seen and

the storm was over. “That was the one,” my late father told me later, “the

wihtiko. The one you tracked is the one that the white man killed at Flin

Flon. It nearly got there.”And then one time he went to lift his traps in the spring, as usual.

Already, somebody had been there getting his traps and dragging them out. His

beavers had been dragged out and left in the open, where ravens were ravaging

them. “I wonder who is doing this,” he thought. “It can’t be a bear, because

it would have eaten them, the ones he dragged out. Ah, but wait!” He thought

about it. The next day he went to lift his traps very early. He just went to

watch for it. As he came around a bend, there it stood, with its back to him.

It was a human while he was looking at it. He shot it. Boy, it went to the

shoreline fast. It was gone, but he knew he had hit it. He did not go to

investigate, though. There was no sound from it. “I guess I killed it right

there,” he said. “I was able to kill it because it was thawed out already. I

must have killed it there. I did not go and check on it, though.” And then

he started to kill a lot of these wihtikos. He’s the one that did it. Nobody

ever bothered him again.Links

American Indian History and Related Issues

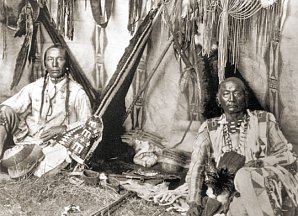

h-amindian past photos

American West Photographs

North American Indian Photo Portfolio by Edward S. Curtis

Native Technology and Art

The Powwow Editions

PFC Piestewa Legacy Blog

Kootenay Digital Photo Albums

Native American Actors

Indian Quotes

Native Wisdom

Official Will Rogers Website

Will Rogers

Pukatawagan: Reflections of a Wimistikosiw Visitor

![]()

WEBZINE

ARCHIVE

Hillman

Eclectic Studio

All Original Work ©2009/2014 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners